PARALLEL JOURNEYS

Dedicated to Jack

International Copyright Jonathan Zap, 2023

Published 5.5.2023

BOOK ONE BIOSPHERE 3

1 My Name is Tommy

My name is Tommy, and I’ve been sealed in this biosphere for three years.

I had only just turned sixteen when I entered, and the life I once had—a beautiful life I could touch and smell and taste, a life full of people I loved and who loved me—is ever more distant, like the receding home planet of a space traveler on a one-way trip.

With zero evidence of any other survivors, I’m not even sure what I am now. Does my existence even qualify as a life?

A horrible image keeps rattling through my head. A pair of flies buzzing around in a Coke bottle buried in the desert of a dying planet. Putting such dark thoughts into words feels like treason, but I need a place to express what I’m feeling. I need it to keep going.

There’s a grim truth that gets worse every day. The biosphere has a room full of scanners and terminals linked to several satellites, and yet we haven’t picked up a communication signal of any kind in almost three years. Total radio silence from the whole planet. So yeah, Kyle might be the only human face I’ll ever see again. And Kyle—well, I’ll get to Kyle.

Based on the information I got in social isolation training, it’s a near-miracle we’ve survived three years without either of us having a psychotic break. But I might as well confess now, I’ve been allowing the voices in my head to speak to me as other people. I realize it’s a classic isolation symptom. It might border on some kind of multiple personality disorder, but I think I’d be in far worse shape if I didn’t allow it. Sometimes I hear the voice of Rachel—Dr. Rachel Miller—the psychiatrist who counseled me before I was sealed in here.

“We’re social animals,” she often said.

So, if there are no other people, it becomes necessary to invent them?

“Yes, Tommy. And it’s better to allow yourself to knowingly invent them before they become uncontrollable hallucinations.”

See what I mean? That’s not something Rachel actually said during training. It’s what she’s saying in my head right now. It sounds sensible, like something she’d say if she were still alive. But it’s also a sign I might be going crazy. She once told me that if you doubt your sanity, you probably aren’t insane. I really hope that’s true.

Part of why I’m writing this journal is to try to break out of my disassociation. I’ve learned to numb myself as I go through the motions of my daily tasks and responsibilities, but I barely feel alive anymore. I need to become more human again. More Tommy again. I can’t allow myself to break down. But if I am going crazy, this journal might be the only safe place to let it happen. The only safe place to pull myself together. I can’t let Kyle see me like this.

Although there’s no evidence of other survivors, it doesn’t mean there aren’t any. Maybe they’re lying low, being careful not to emit electronic signals and draw the attention of anyone who might threaten their shelter. As unlikely as that is, I can’t abandon my post while it’s still a possibility. And that means I need to help maintain Kyle’s morale as well as my own.

I haven’t confessed anything in this journal until now because everything I write becomes permanent. It’s kind of a weird setup, so I’ll explain how it works. Inside a steel vault is a titanium sphere containing a small transcriber device. If I stop for ten minutes, the machine laser-inscribes everything I’ve typed onto a single, gold-plated disc. It’s like an old-fashioned DVD, but it’s meant to last forever. Like a time capsule. The vault unlocks automatically a year after the biosphere is unsealed. I guess they thought it would be a record of a historic experiment. But right now, it feels like the black box in an airplane recording the last moments before a crash.

With his tech skills, I’m sure Kyle could break into any other computer in the biosphere. But each of the sixteen dorm rooms—fourteen of them empty—came equipped with a journaling terminal connected to the transcriber by a single fiber-optic cable, that no one—not even Kyle—could get into. After ten minutes of inactivity, a timestamp is added to the end of an entry. Then the text is permanently inscribed. Everything we could ever write will fit on that one disc. But right now, my words are still in limbo. I could delete them, and no one will ever know they existed.

I feel like that myself. We are, as Rachel said, social animals. So if there’s no one to observe my life, the real-life of who I am inside, a life I do everything I can to keep hidden from Kyle, then—Is it even real? That’s the kind of question that invites madness. I need to make my inner life real to keep myself from falling apart, even if the only witness is a machine. So . . .

2 Breaking My Blood Oath

There. It’s real now. Knowing my words are recorded makes me feel more solid. I’m leaving a mark someone might read one day. But the price of this record could be my life. A couple of weeks after we sealed, I swore a blood oath to Kyle not to disclose certain things about him. Now I need to break that oath. To tell my story, who Kyle really is must come out. But if he finds out about this—well, I just have to make sure he never finds out.

Am I being selfish in taking this risk? I’ve often wanted to end my life, so maybe I’m just reckless. But the possibility that someone might read this gives me the feeling that my life still serves a purpose. It could be a necessary madness brought on by isolation, but I feel someone will read this. Maybe that person isn’t even born yet, but I feel you out there, wanting me to continue. At least, that’s what I’m feeling right now. A rare moment of hope. It won’t last, but I’m grateful for it anyway.

I want to believe Andrew will read this one day. For years, it’s felt like we’re living parallel lives, but he always remains out of reach. I realize it’s almost impossible that he’s still alive, but he haunts my thoughts. My whole life has been guided by strange intuitions about impossible things that somehow became real. So why should Andrew be any different? If I’m honest though, even before the plague, I couldn’t be sure he was alive. I just can’t

3. A Map of Where to Find Him

I’m back. We just had a false fire alarm. A sensor picked up some anomalous hydrocarbons in a hallway near cryogenic storage. Gaia, our main computer, interpreted it as possible combustion, but we couldn’t find anything amiss. We get a lot of false alarms due to our super-sensitive air sensors. You can’t let anything toxic leak into the air of a sealed biosphere. A loose cap on a tube of glue is enough to set them off.

Kyle inspected the hallway suspiciously, checking everything with an infrared scanner to see if anything was overheating. Finding nothing, he cleared me to go. He usually contains his stress and is hard to read, but for some reason he seemed really on edge. I wonder what he was working on when the alarm got tripped. As he walked away, he flashed me a paranoid look, as if I had purposely set up the false alarm to distract him from something.

Maybe he’s aware that I’m finally using my journaling terminal? If he’s monitoring changes in the wattage going into my dorm, he could tell I’ve turned it on. But we were strongly encouraged to use those, and there shouldn’t be any way for him to know the actual words I’m writing unless he’s messed with my terminal or keyboard, and we were told those were made to be tamper-proof to ensure privacy.

What if he set up the false alarm because he wanted to stop me from journaling?

No, that doesn’t make any sense either. The interruption was more than ten minutes, so everything I wrote is permanently inscribed, and I’m still journaling. Rachel warned me that paranoia is a dangerous isolation symptom, and I can feel it infecting both of us.

Anyway, sorry about where I broke off. I didn’t mean to speak in riddles, but now I can’t delete that line about not being sure if Andrew was alive even before the plague. I hope this will make more sense once I tell you about my first encounter with him. Somewhere within that encounter lies a map of where to find him. And hopefully, a way out of this impossible situation. Unfortunately, it’s a map I’ve never been able to figure out. As important as that encounter is to me, I’ve never actually written it out. Maybe once I do, I’ll finally see the map.

It happened three years ago, just a few months before the plague, but it’s still my most vivid memory.

It begins with me picking blackberries. I’m in the woods near the settlement I grew up in, deep in a valley of the Green Mountains of Vermont. My basket is nearly full when a wave of slowtime passes over me. I need to be alone when this happens. I’ll explain it later, but slowtime forces me to see into other people more than I want to—behind their thoughts and feelings. And that’s like disrespecting their privacy. So I take my basket and disappear into the woods to hide out in my treehouse.

From its high cedar deck, I look out over the sea of leafy branches and rolling hills that form the valley I live in. Gusts of wind rustle the canopy of leaves around me. The wind calms as the sun breaks through the clouds and lights up the forest with its golden rays. The warmth on my skin melts my uneasiness. I undo the tie holding my long, blonde hair and lie back on the deck. The grain of the cedar planks against my skin, and the smell of the newly sawed wood, make me feel like I’m on an old ship, sailing under the sun.

A fresh wind carries the evergreen scent of fir trees from deep in the valley, bringing me back to where I am. My sensations become intensely vivid, like I’m feeling everything for the first time. I reach into the basket, wanting to taste the blackberries.

They’re sweet and smooth, almost bubbly, sliding on my tongue. My senses cross, and their flavor becomes a deep purple light flowing into me.

Slowtime stretches every moment.

A great horned owl soars into view. I can see the brown and white stripes of its wind-ruffled feathers in perfect detail. The owl is like a banner rippling in the sky, bringing a message. It passes overhead and screeches, sending a current of fear through me. As the owl flies off, a strong gust of wind pushes dark clouds across the sun. I hear a distant rumble of thunder coming from the western part of the valley, followed by more gusts of wind. The sudden chill forces me to sit up and hug my knees to my chest for warmth.

The howling wind is making me shiver. The shivering builds until it becomes violent. It’s almost like a seizure or being electrocuted.

And then I become the electricity.

I erupt from my body into the howling wind, swiftly ascending toward the dark clouds above.

I look down and see my body on the deck of the treehouse, shrinking away as I rise higher and higher. I’m still sitting there hugging my knees, the windblown tree branches moving chaotically around me. But it’s too weird to view myself this way. I feel intense vertigo, like I’m about to plummet. A dizzy moment of panic throws me, and I drop—

Suddenly, I’m standing a half mile away at the edge of our land where it meets a dirt road that heads to Bridgeton. I take a deep breath. The ground beneath my feet feels solid. I look around. Everything is familiar but—

Something’s wrong.

There are no storm clouds anymore, but the air is smoky from distant fires. The sugar maples are orange and red, and there’s a chill in the air. It’s as if I’ve gone from summer to autumn in the blink of an eye.

I turn toward the dirt road and see the new gate we put up in late March.

This isn’t a memory.

Sticking out of the ground beside the gate, like a green nylon tombstone, is my backpack. It’s bulging unevenly because I packed it in such haste. A sense of urgency rushes through me.

I need to move. Now!

I reach for the pack to hoist it up. It swings wide and slams against my back. A realization erupts inside of me.

There’s no one left for me to help. Everyone but me is dead.

The moment repeats.

SLAM—

There’s no time for grief. Danger is close. I have to move quickly and be ready to hide.

SLAM—

What I feel doesn’t matter. My mission is all that matters.

SLAM—

The final slam jolts me back into my body on the treehouse deck. I’m sitting exactly as I was before I was pulled away, arms wrapped around my knees, but I can still feel the impact of the backpack in my bones.

The wind settles. Though the sky is still overcast, it’s no longer darkened by thunderclouds. The warmth of the humid air stops my shivering.

I sense someone is with me, watching. I can’t see anyone, but I feel their gaze emanating from a point in space about ten feet beyond my treehouse deck. I stare in that direction until an outline of light begins to form. From its center, a boy about my age comes into shape.

He’s glowing and not quite solid in the way I am. As his body takes on definition, I discover something terrible has happened. His clothes are burnt, and much of his skin is charred. I try to hide my shock at the sight of his burns. The fire hasn’t touched his face, so I focus on his intelligent, brown eyes looking deeply into me. I’m struck by how calm and aware he seems, even though he’s in such a terrible state.

I think of my volunteer work at the hospice. I’d been with old people as they transitioned at the edge of death. Sometimes they communicated with me. Other times they’d just look back at their body and depart.

But he’s my age. He needs to live.

As I look into his eyes, it’s like I’m being seen for the first time. Understood for the first time.

I want him to live. I need him to help me understand what just happened—what’s coming—it feels like there’s something important we must do together—

Like knowing in a dream, I realize certain things about him.

We’re so different.

He’s grown up in a city world with books and complex ideas. His dark hair and eyes against his pale skin suggest an ethnicity I can’t name. We’re from different backgrounds and even different bloodlines. And yet, there’s a bond of brotherhood between us. Whatever’s coming has brought us together. I sense he understands much of what I do about this moment. His dark eyes are like portals of awareness, and I want to know the depths he’s seeing. It’s the moment to say something.

“Hey.” Despite the strangeness of the situation, I keep my voice calm and friendly. “I’m Tommy. What’s your name?”

“Andrew,” he replies.

“Welcome to my treehouse, Andrew. Can you—would you like to sit with me?”

He looks at me uncertainly. I smile and pat the deck with a welcoming gesture. He flickers for a moment and suddenly is sitting across from me. Closeness makes him seem more solid, and I realize that he’s not only my age but almost exactly my size. I want to hug him, my usual way of greeting people, but I don’t want to shock the fragile sort of body he’s in.

“Where are we?” he asks.

“Vermont. A valley in the Green Mountains.”

He turns to look out, but as soon as we break eye contact, his body begins to thin. He looks back in a panic, and our gazes lock as we realize something. We need to stay focused on each other to keep him in my world. So I slow my breathing and surround him with my energy to help him stay with me.

“What happened to you, Andrew?”

“I was . . .” Andrew hesitates, and his vision turns inward for a moment. “I found myself looking down at the wreck below. There were two smashed-up metal hulks. Smoke was coming from the one that was once our—”

Andrew breaks off, his eyes fill with tears and cast downward as if he’s still seeing the wreck. His body trembles, and I feel him trying to contain his feelings. I sense he’s afraid they’ll disturb me. He gathers himself, and when he looks up, his eyes are haunted, but his voice is calm and almost trancelike.

“There was broken glass everywhere. Flashes of red and blue lights from emergency vehicles lit up the fragments like rubies and sapphires. It all looked so strange, but sort of eerily beautiful too. There was a feeling everything was exactly the way it was supposed to be. The wreck was just something that unfolded in time—like a flower bud opening its petals.

“I let go of it and ascended into space. And . . .”

Andrew seems confused and hesitates, looking downward again. It’s like he’s realizing he shouldn’t tell me certain things. When he looks up, his gaze steadies.

“I blacked out. And when I woke up, I was floating near your treehouse.”

“Well, I’m really glad you found me,” I say with a welcoming smile.

“I’m glad you found me too,” he replies. “At first, you didn’t see me. I watched you. I saw you shivering, and it made me feel cold. Then, when you rose out of your body, I went with you, almost like we were the same person. I saw and felt with you. I think I know what it all meant. Something’s coming. Something like . . . what just happened to me. But . . . for the whole world.”

I let out a breath, grateful that Andrew experienced the vision with me. I’m about to ask him more, but something in his gaze quiets me. We look into each other’s eyes and then . . .

We merge.

It’s like we fell into each other. We were still ourselves, only swirling together without our bodies. Two sides of the same being. I really can’t describe it any better than that. I saw with my soul instead of my eyes, like some kind of revelation.

We separate. We’re still sitting across from each other on the treehouse deck. Andrew gives me an intense look.

“Tommy—” he begins to say when an electric shock arcs through his chest. His body seizes, and he vanishes in a flash. It happens so quickly I can’t even react. The empty silence he leaves behind is crushing, and there’s a painful moment where I’m afraid I’ve lost him forever.

He was ripped out of my world, and I’ll never know—What, Andrew? What were you going to say?

And then, I hear him.

“Tommy . . .”

His voice seems to stretch across space and time, like it’s traveling an impossible distance to reach me. An echo of an echo.

“This is a map of where to find me.”

The words are urgent. Pleading. But I can’t make out what he means. I’m waiting for something more, sitting at the edge of the deck, listening like I’ve never listened before. But all I hear is the wind.

In my mind, the echo of his words trails off.

This is a map of where to find me . . . a map of where to find me . . . where to find me . . . find me.

I stay on the deck for quite a while—an hour, maybe longer—searching for a trace of his presence. Hoping for something more. He’s gone, and yet I sense that wherever he is, he’s as desperate to reconnect as I am. Before I climb down, I take a last look around. There are only treetops as far as I can see while the sun drops toward the ridgeline in the distance. I don’t know if my words will reach him, but I whisper a promise into the silence.

“Andrew . . . we’ll figure it out.”

4 His Voice Echoes

His voice still echoes within me.

For three years now, I’ve hoped and prayed Andrew made it back to his body. But he looked so badly burned. Even if he survived, his life would be painful and difficult.

So maybe I’m being selfish to hope he’s alive. But I want him to look at me again with that deep understanding. I want to know what he saw in me during our merger, and what he thinks all of this means. I need him to share the burden I feel.

Yeah . . . I guess that is selfish.

I still need to

5. Magical Thinking

Sorry, another false alarm, but this time we found the cause—a smoldering circuit board that controls a water pump near cryogenics. Fortunately, a replacement was easy to locate and install.

Anyway, I scrolled up to see the last thing I wrote—about it being selfish to hope Andrew is alive—and maybe I shouldn’t have written that. It’s probably what Rachel called survivor’s guilt. I might have selfish desires, but the need to find him feels like it serves something larger. Merging with Andrew was the most profound experience of my life, but I don’t know how to put even part of it into words. We were together in a dimension that felt like it was above time.

Normally, I have so much work to do I have to keep running from daytime to nighttime to daytime and on and on. Just one damn thing after another, as they say, to keep this place going. So I keep running on my hamster wheel. But it’s not just me—that’s just the way time is—the wheel keeps spinning whether you want it to or not, and you’ve got to keep up.

But Andrew and I encountered each other in a di mension beyond the hamster wheel—the Nowever.

“Tommy, you need to reality-test your belief in Andrew. Do it now, and in writing!”

Rachel just harshly broke in with that. When she’s warning me, it’s not like this whisper of suggestion—it’s more like she’s trying to slap me awake. Her voice can be severe, but I’ve got to respect her advice because she’s given me survival warnings that probably saved my life.

But I can’t just follow what a voice tells me. That would be totally irresponsible. It’s up to me to decide if my thoughts, or anyone else’s, are right or not. Rachel isn’t the voice of God. Logic isn’t the voice of God either. And even if I thought I was hearing the voice of God, if it told me, like Abraham in that Bible story, to kill my son or something like that, I’d disobey. I’m not crazy enough, not yet at least, to let voices command me. But I do take Rachel seriously even if there are parts of her advice I don’t follow.

The way Rachel described the need to reality test made it sound like more than advice. It felt like her religion.

“Reality testing must be a daily and hourly practice,” she once told me. “You must be in the habit of applying it to any thoughts that are elaborate and removed from physical evidence. A mind stressed by isolation drifts into magical thinking, and if you give such thoughts energy, they will pull you into psychosis. You must use reality testing to defeat magical thinking!”

Something inside me rebelled every time she said, “magical thinking.” It was too risky to tell her about my life-changing paranormal experiences, especially my encounter with Andrew. If I confessed, she would have said I had a hallucination and was giving it energy with magical thinking. And then she might have felt duty-bound to disqualify me from the biosphere.

Rachel always meant well, but she didn’t have the paranormal experiences I had—experiences that were not just real, but far more real than anything else in my life. But that doesn’t mean I should ignore her advice. She’s the one who tried to help me the most. The only training I got for living in isolation was from her. She gave me the tools that have helped me survive and stay at least partly sane. And I’m ashamed that I didn’t give her the appreciation she deserved when she was alive.

She was so serious when she told me, ”Stay vigilant, Tommy. When magical thinking appears, reality test it!” The way she said reality test it! sounded like she was saying, Reality test the shit out of it! She said it angrily, like reality testing was a sledgehammer and magical thinking was a wingless fly begging to get squashed. But anger isn’t logic. It felt more like a strong prejudice. Like angry reality testing was her religion.

But I haven’t found magical thinking so easy to get rid of. And with Andrew, I don’t even try because I need to believe in him. Rachel told me to deprive magical thinking of energy. I do the opposite. I give a lot of energy to Andrew, and my thoughts about him are elaborate and without evidence.

By not reality testing Andrew, I know I’m disobeying Rachel, and I feel how disrespectful that is. I owe her more than that.

I’m sorry, Rachel, I should have followed the practice a long time ago. I’m going to make some strong black tea, and then I will reality test Andrew with logic and rules of evidence, like you said.

6 Reality Testing Andrew

The first thing I notice when I apply logic, is that Rachel’s advice is contradictory. She died before the seal, so her telling me now to reality test, fails reality testing. But to be fair, she gave the same advice when she was alive, so that doesn’t excuse me from applying the practice. So here goes.

I’m living in social isolation, and my emotional life revolves around someone who isn’t physically present. I have zero evidence that Andrew exists or that he ever existed. Although he feels real, Rachel told me that people often adapt to isolation by creating imaginary companions. So, the logical explanation is that I’m hallucinating an imaginary friend. Andrew is just my version of Sugar-Candy Mountain, a wish fulfillment kept alive by magical thinking. That’s the answer to the reality test she would consider correct.

But it’s just not what I feel from my depths. Andrew is another person. And there’s an unfinished destiny between us.

Neither of us said it, but I think we both understood we were being called together to serve a larger purpose. So it’s not just selfish that I want us to reconnect. Andrew followed me into a prophetic vision I was having about the end of the world—the reality I’m living in right now. And it’s always felt like he knows more about our shared mission than I do.

No matter what reality testing says, the encounter with Andrew seems like the most real thing I’ve ever experienced. I’m going with it because I need it to keep going. And that means I need to decode the map of where to find him.

I’ve searched our archives for any record of a boy named Andrew in a car accident with his parents on that date. But that type of search has never turned up anything. There’s some pattern I’m not seeing. Maybe it’s because everything in my life that led to my encounter with Andrew was also part of the map?

I don’t know. But maybe I should expand the edges of the map and start with my life before the plague. After all, my encounter with Andrew wasn’t my first experience with the paranormal.

I was already changing that summer, before we even knew about the virus. Of course, any fifteen-year-old is going through changes. That’s normal. But I was changing in ways that weren’t. Looking back, I think something in me must’ve known the plague was coming. My new abilities began to surface only a few months before I’d need them to survive.

It was a beautiful time of year where we lived, in the Green Mountains of Vermont. We were a small community of twenty called “The Friends,” which you may know as some Quaker thing. They loosely inspired our customs, especially our commitment to nonviolence. Like Quakers, we saw each other as friends, and our meetings were similar in some ways. They happened every month, and anyone who felt called to, including kids, could speak. But, like I said, loosely inspired. We had a few shared values, but we didn’t impose religion on anyone. We also applied our nonviolence to the land and lived sustainably.

7 Where I Came From

Sorry, I had to take a break. I guess I knew this part would be hard to write about, but I need to tell you where I came from. I had such a great life then, and it ended so suddenly.

One day, I’d like to write a whole book about each person I grew up with, but at the moment, I can’t face all that loss. So for now, I’ll just tell you what I can about my former life.

My education was a type of alternative homeschooling set up by what’s called the Sudbury model. No kid was forced to learn anything. Even from an early age, we picked subjects based on what we were into. Schooling wasn’t scheduled according to a program, or for a certain time. My life was my schooling, and my schooling was my life.

For example, my mom, Eleanor, read me storybooks. When I wanted to learn how to read them for myself, she taught me. Soon I wanted to write, so she taught me that too. I saw Mark, who used to be a major graffiti artist, spray-painting an amazing mural for our meeting hall. Seeing my interest, he gave me art lessons.

I spent time with Dorothy learning herbalism, nutrition, and cooking. Later she taught me how to make essential oil blends which were carried by a few local stores. I learned about farming from everyone, but especially Josh, Jordie and Scott, who were trained in permaculture. I worked beside them, doing every specific task from tending to our beehives, to grafting vines onto hardier rootstock, and animal husbandry. They showed me how every part of the farm functioned together as an ecosystem.

We were free to learn from people or sources outside the community too. If we wanted to use the internet, we’d catch a ride to the public library. Our community was intentionally low-tech in that sense. We didn’t use smartphones either, so we spent more time with each other than with screens. From an early age, I felt different than the other kids I saw in town who were always lost in their phones.

At ten, I had a strong urge to volunteer at the hospice in Bridgeton, where my mom worked. I know that wanting to work with dying people is a strange calling for a kid, but I felt deep inside that I should do it. I also didn’t want to selfishly use up resources without giving anything back. Helping out at the hospice and within our community, gave me a sense of purpose.

The hospice was my most meaningful work, but I spent a lot more time on woodworking, which I learned from Matthew, our master carpenter. We made one-of-a-kind furniture, boxes, mirrors—all sorts of beautiful things. A large craft co-op on one of Burlington’s main streets carried our work. People bought whatever we made as fast as we could make it, and it helped fund our community. Matthew was also the designer of our meeting hall, cabins, and workshops. We all helped with the building, but he guided us every step of the way.

At fifteen, I‘d already been Matthew’s apprentice for a few years. People said I was a fast learner. There was some truth to that, but it didn’t hurt that I lived with my teacher and spent most of my time enthusiastically learning my craft. In our last winter together, Matthew and I worked on a new project—handmade kaleidoscopes. We ordered front-coated mirrors, lenses, a laser cutter, and hardwoods with interesting grain patterns—rosewood, poplar, walnut, and teak. This allowed us to create intricate inlays. It was the first project where we worked together like equals.

When spring came, Matthew announced I was ready to design and build my own completely independent project. I’d always been drawn to the forest, so I began researching treehouse builds. I discovered techniques that didn’t require putting nails into the trees, and as I worked, I came up with some of my own innovations that allowed me to save weight and put less stress on the tree.

Building the treehouse was my initiation into what it was like to work on my own, and every part of me rose to the challenge. At the same time, I was going to the hospice a couple times a week, handling farm chores, cooking, and helping Dorothy make essential oils. So to get the treehouse done, I had to work more efficiently. I was busy doing something every minute.

I loved everything I was doing, but at the same time, I was uneasy about myself. I was going through an unusual kind of growth spurt. It wasn’t so much about getting bigger, but growing in other ways. I got much faster with my craft and chores. And as I got better at anything, I seemed to get better at everything.

It was great being able to do tasks more quickly and efficiently, but I soon discovered that what seemed natural to me, didn’t seem that way to others. There were raised eyebrows when people saw how quickly I was moving. It made me really self-conscious. I didn’t want people around when these speedy phases came over me, so I figured out ways to do my work in private.

Hiding became its own skill. If anyone approached or even looked in my direction, I could feel it, and I’d slow down to a more normal speed. But when no one was around, I went with the waves of speed—what I call “quicktime.” It felt great while it was happening, but I sometimes felt guilty after. We were such an open community, and I was hiding something from the others. I knew quicktime wasn’t normal—that I wasn’t normal—but I didn’t want to worry anybody about it.

I also found myself entering these zones of what I call “slowtime.” It tended to come over me when I wasn’t busy doing a chore. Like maybe I’d be out walking by myself, and it’d just take me. But other times, I was more in control. I could usually bring it on just by sitting still and breathing deeply, almost like a kind of meditation. But sometimes, weird stuff happened once it kicked in.

When in slowtime, I didn’t move any slower than normal. It was more like everything around me, especially people, slowed down. I always tried to avoid others when it was happening, because I saw more deeply into them than I had a right to. I felt their innermost feelings, which seemed wrong, like an invasion of privacy. It made me uncomfortable around people. Knowing who someone was on the inside, made it harder to relate to who they wanted to be on the outside. So I tried to resist slowtime unless I was alone.

The only exception to this was when I would sit beside a dying person at the hospice. When it felt right, I’d close my eyes, take a few deep breaths, and allow slowtime to take hold. It let me feel closer to them and sometimes share their experience at the edge of departure.

I hid this part of my hospice work. But I didn’t feel guilty about it. If the other hospice workers knew how strange the shared experiences were, it would only raise doubts about whether a young kid should be there at all. At least some of them would think this work was causing me to become delusional.

They could see my visits were calming, but it was better if they thought I was helping just by my presence. Like the way spending time with a dog or a cat can help a sick person.

What I saw and felt in those moments was part of a bond between the dying person and me, and the experiences still feel too private to write about. Also, my mom always told me that if you work with patients, everything is supposed to be confidential.

Anyways, a few days before the summer solstice, I finished my treehouse. The Friends gathered there for a brief ceremony, and everyone got a tour. Then it became my private space. Although I had a room in my mom’s cabin, this was the first time I had a place to myself. At night, I pulled up the rope ladder, sealed the floor hatch, and was totally alone.

I designed the treehouse to look like a wooden ship, and I even called it the Tree Ship. I didn’t share that name with anyone else, but it’s how I thought of my treehouse. When the wind blew, it moved slightly with the branches like it was sailing on waves. Slowtime often came over me there, and I went with it into many strange experiences. And that’s how I met Andrew. Someone who

8 The Whip

Sorry, same damn fire alarm! The new circuit board started smoldering too, so it looks like a grounding problem or a bad transformer. Kyle’s working on it.

Anyway . . . a couple of weeks after I encountered Andrew at my treehouse, everything changed. That’s when we started hearing about the plague. It had a terrible name, “The Whip.” They called it that because it created lesions that looked like whip marks.

The virus was artificial and engineered to be as deadly as possible. It had been released in several international airports but was designed to remain dormant for months. So it spread invisibly across the planet before being detected. There were lots of conspiracy theories about who made The Whip and why. Many believed that a sentient AI had created it to rid the planet of humans. The government denied knowing its origin, and if anyone on the biosphere team knew the source, they never told me.

Like I said, The Whip was undetectable during its dormant phase. But it had a time trigger. It came out of hiding in late July and began replicating and mutating into multiple lethal forms. Many people died as soon as three days after the first appearance of symptoms. Others bore its marks—the whip-like lesions—while they slowly weakened and collapsed into a high fever. Finally came convulsions and bleeding out.

The final stage turned the cells of the dying body into a Whip factory, pumping virus into the air like a cloud of deadly spores.

The danger of this last stage was so great that governments began distributing “The Dose.” It was a little bubble pack of pills. If you took them, you went unconscious in a couple minutes. Once you were out cold, it paralyzed your breathing and ended your life painlessly. Government-subsidized mercy killing.

The Whip mutated too fast to create a vaccine. To overcome immunity, it had been designed to use the illness’s final stage to generate new variants. Some totalitarian countries tried killing the infected and burning the bodies. But attempts to control the virus quickly descended into chaos. When the soldiers commanded to carry out the killings became infected, they turned their weapons on their superiors.

Like all medical facilities, the hospice was taken over by the military. They turned it into a Dose distribution center. The Friends retreated to our settlement in the woods to care for our own. My hospice work helped prepare me for what followed. My mom was a nurse, Dorothy was a licensed midwife, and the three of us worked side-by-side, tending to the dying. We worked around the clock and barely slept, doing whatever we could to give our friends as dignified a death as possible.

A lot of our care was about respecting how long people wanted to go into the illness and stay aware, versus when they wanted to be more sedated or felt ready for The Dose. Some of them wanted a little more time to reflect on their lives. Mostly I was just staying with someone—holding their hand and giving them a chance to talk if they wanted to.

My mom died on September 24th.

9 Discovering My Mission

Dorothy and I were the only caretakers left. At that point, she was already sick, but she kept going so long as anyone needed help. Finally, when the last patient in our care, Jordie, died, she collapsed. Within a few hours, Dorothy was gone too . . .

Why am I the only survivor?

When I thought about it, I realized that all along I feared others getting sick, but never myself. I know lots of people are fooled by “it can’t happen to me.” But this was different. It was another case of strange intuition—what Rachel called magical thinking—turning out to be right.

At the time, surviving felt more like a curse than a blessing. It still does, but I’ve grown used to living with the feeling. But when all the other Friends died, I was still a newborn in the world of despair. With no one left to care for, there seemed no point to anything. It was like everyone else had gone away and left me behind. I just wanted to go to sleep and join them wherever they were.

I slumped onto the floor of Dorothy’s cabin, and within moments, exhaustion took over and pulled me into sleep.

While I slept, my mom visited me in my dreams. I’d had experiences at the hospice watching patients cross over, but this was the first time I’d seen anyone cross back. And it was my mom.

She’s kneeling before me, radiant and younger than I’ve ever seen her. The way she must have looked in her mid-twenties, just before I was born.

The sight of her is overwhelming.

“Mom?”

“Tommy. My beautiful son.”

“You’re—”

“I’m fine, Tommy. Please don’t worry about me. I love you, but you need to take care of yourself now.”

She looks into my eyes, and it feels like she’s looking into my soul.

“Tommy. . . I can see the beginning of your journey. The world is dying, but you must live. So much depends upon you . . . you’re needed to do something crucial, and you have everything within you to survive and serve this great purpose.

“But you can’t stay here any longer. Dangerous people are coming. You must leave here right away.”

“But mom, leave to where?”

“I’m sorry, Tommy, I don’t know, but your purpose is about to be revealed. Go wherever it requires you to go. Walk along the edges of the roads. Let no one see you. Use everything you learned with The Friends, and we’ll always be within you.

“Stay alive and fulfill your mission. Tommy! GO—”

Her last words are so urgent they jolt me awake. I shoot to my feet and hear voices outside. I fear they’re the dangerous people my mom warned about. Overcast morning light is filtering through the windows, but when I steal a glance outside, I find everything’s shrouded in a thick fog. Smoke from distant wildfires has been getting worse every day, and I can’t see where the voices are coming from.

The quickest path to the woods from Dorothy’s cabin is a few yards from her back door. I creep quietly over to it, ready to run. I’m about to break outside, when I stop to listen more closely and realize the voices are coming from a radio in a nearby cabin. They’re giving instructions on how to burn the dead, and then there’s a bulletin—

“It’s crucial we locate anyone who may be immune to the virus. If you’ve been heavily exposed but are completely symptom-free, you must get tested. You may be our only hope of finding a cure. This is a nationwide search. There are testing facilities in every state. In Vermont . . .”

The closest facility listed is in Burlington, about seventy miles away.

This must be the purpose my mom was talking about!

A wave of quicktime comes over me. I use it to gather what I need—water, food, flashlight, sleeping bag, bivy sack—and shove them into my backpack.

I can balance the load later. I need to go now.

When I hoist the pack, its uneven weight slams against my back. The impact ripples with déjà vu—storm clouds, desolation, Andrew—but I can’t think about him now.

When I reach the gate at the edge of our land, the gate from my vision, there’s still no sign of anyone approaching, but I know I need to keep moving. I walk a few steps down the road, then turn back to look at our settlement. The place where I was born and spent my whole life. I know I’m seeing it for the last time.

There’s an old bandana around my neck. A gift from my mom. It’s deep purple and spotted with little orange flowers. I’ve had it for as long as I can remember. I don’t know why, but I take it off and tie it to the branch of a hawthorn tree leaning out over the road. It hangs there like a trail marker. Then, before the wind has time to lift it, I turn and start my journey.

As my mom advised, I walk along the edge of the dirt road. The radio had warned that prisons were not being maintained—they had all been unlocked and abandoned. It was advised to use extreme caution when traveling. About fifteen minutes into my walk, I hear a vehicle approaching and duck into the woods, hiding behind a massive oak. I peer out as it passes, catching enough of a glimpse to see a large, red pickup truck. It slows near me to go over a rough patch in the road, and as it passes, I hear the shouts of a bunch of guys arguing with each other. They’re speeding right toward our settlement, and I’m sickened by the thought of them invading it, but there’s nothing I can do.

I keep hiking, maintaining a high pace well into the night before I set up camp. A crescent moon hangs coldly above me as I crawl into my sleeping bag inside my bivy sack and surrender to sleep.

When I wake up, there’s smoke in the air again from distant wildfires. They were happening more often even before The Whip, but now, with too few left to fight them, they’re just letting them burn. I hadn’t brought any masks with me, and I left my bandanna on that tree, so I pull my only other shirt out of my pack to tie across my face.

I packed light so I could hike faster. I’ve got only one water bottle and a filtration straw. For food, I have a large bag of raw almonds and another of dried apricots. It’s enough to keep me going. By nightfall, my feet are aching from hiking all day, and my eyes and throat are irritated from the smoke.

On the third day, I get caught in a vicious thunderstorm. I have a water-resistant parka with me, but in my haste to pack, I forgot a key part of my wilderness survival training. All the clothing I have with me is made of cotton, including my denim pants. When they get soaked in a cloud burst, I remember Matthew calling denim, “death cloth,” and warning me that most hypothermia fatalities aren’t caused by extreme cold, but usually happen at moderate temperatures when people wear cotton clothing, especially denim, in the rain. Thank God for the parka, or I would have been completely soaked. Even so, I have to hike really fast to keep from shivering, and my wet boots and socks blister the hell out of my feet.

Eventually, the storm blows off and another three hours of fast hiking into a headwind dries out the denim.

I’m only a few miles from Burlington when I set up camp that night. I’d been there many times with Matthew making deliveries to the craft co-op and thought of it as a wealthy tourist town with lots of stores. I fall asleep uneasily, sensing danger.

The following morning, my fear intensifies as I approach the edge of town. Most of the store windows are smashed, and broken glass is everywhere. I reach the craft co-op where most of the stuff Matthew and I built was sold. The windows are shattered, and the place has been torched. I recognize the charred remains of our furniture and the best kaleidoscopes we ever made.

I can understand people taking things they need, but this is just totally pointless destruction.

The sight of it hits me hard, and I can’t hold back my tears, but I push on toward the testing site.

There’s no sign of women, children, or old people anywhere. The only ones on the street are a few sketchy-looking guys. Most of them are shuffling about in a sick haze, while a few healthier ones loot what’s left of the stores.

I try not to draw attention, but there are no woods anymore. I’m in plain sight and have to travel through the streets to get to the testing center.

“Hey, I got somethin’ for ya,” a guy says from the entrance of a looted store.

I sense his bad intentions in every cell of my body.

Growing up, I often got compliments from adults about my looks. But it was harmless stuff—what you expect to hear as a kid. Now my appearance has a completely different meaning—it marks me as prey.

Just as the man rushes toward me, I take off running down the street. Thankfully, I’m much faster, and he can’t catch up. As soon as I lose him, I slow down to avoid more unwanted attention.

I pull up the hood of my jacket to cover my long blonde hair, but nothing can keep me from standing out. Many pairs of bloodshot eyes are tracking me. And they sense I’m not sick. No one else is moving quickly. Most of these guys lack the energy to chase me, so I walk swiftly, even though it draws more attention.

I’m making my way down Church Street when a guy with a scruffy beard coming the other way passes me on the sidewalk.

He’s staring straight ahead. He seems totally unaware of me, determined to get where he’s going. As we pass, he stumbles and trips in my direction. We collide with a shocking impact as his fist explodes into my face, and I’m hurled to the ground.

My head is spinning.

I’ve never experienced violence before.

The sucker punch should’ve knocked me out, but I will myself to stay conscious. I shake my vision back from the explosion of lights in my head.

Oh my God.

He’s dragging me by the scruff of my jacket, backpack and all, into an alley. The guy is huge, and I only weigh a hundred-and-fifteen pounds.

My head clears, and time slows as he pulls me behind a dumpster. He crouches over me in extreme slow motion. I look up and see the rape he intends burning in the dark pupils of his bloodshot eyes.

Flashes.

Memory flashes from him.

I see him walking in a prison yard like he’s minding his own business. Hidden in his hand is a piece of stray metal he’s sharpened to a razor’s edge. Suddenly he pretends to stumble into another prisoner. He slashes the other guy’s throat in one smooth motion before calmly walking away.

It’s a memory he relishes, and it’s flickering through his mind right now. A triumphant use of his special play, his sneaky way to take someone down before they even see him coming. Now his trick is paying off again.

His blunt and vicious thoughts are like a hammer hitting the back of my head. He smells of sweat and violence. The slowing of time nearly freezes him in place, and I see what he is. All he feels is the gratification of a victim under his control. But he’s beginning to perceive a strange awareness in my eyes. It’s the signal I need to act.

My body knows what to do. My knees shoot up to my chest, and my legs explode outward. The rubber soles of my hiking boots strike his crotch with enough force to slam him against the dumpster. His lower body hits first, and as his spine whips back, his head strikes the blunt metal edge like a gong.

I roll away from his body as it collapses to the ground, spring to my feet, and take off in a full sprint.

A wave of speed propels me to the sidewalk, where I run with bounding strides. Even with a backpack on, it’s effortless, like running in a dream. I no longer care about avoiding attention. People I pass on the street seem impossibly slow. I’m moving through time so differently they don’t even notice me.

Before, I thought of people’s eyes as camera lenses capturing the world in front of them. But now I see them as projectors, shooting energy out toward things to see them. Staying ahead of the sweep of their vision, I’m hidden in plain sight. The ability feels natural, like remembering a forgotten skill. I’m riding waves of survival adrenaline, focused on getting to the testing center. When I finally reach the facility on the south side of town, I find soldiers guarding the entrance. They’re in full riot gear, their hands resting on assault rifles.

“No treatment here,” one of them shouts. “Move along.”

The guards aren’t really awake. Their uniforms make them robotic, and what’s yelled at me is like the barking of a dog guarding a fence. But then I realize my face is throbbing and swollen from the sucker punch.

They must think I’m infected.

I’m usually shy with strangers, but I need to be assertive now.

“I’m not here for medical treatment!” I shout, as one of the guards begins to raise his firearm. “I’m immune! I’m here to be tested!”

The commander motions the guard to lower his weapon. He opens the gate and gestures for me to step in.

Several rows of tents line the open courtyard, but the space feels oddly abandoned. I expected to find a crowd of people waiting to be tested, but there are just a few bored-looking soldiers and a nurse who leads me past the tents to a testing station inside.

A blood sample is taken from me before I’m shown to an empty waiting area. Uneasy minutes tick by as a guard posted by the lab door eyes me suspiciously.

He must think I’m here to steal medical supplies.

I sense when they get the results. A wave of excitement surges through the building. Suddenly, soldiers surround me, and the wave of excitement sweeps me up like I’m being pulled into an action movie.

“We need to pat you down,” a soldier behind me says.

Another searches my backpack and then slings it over his shoulder. They hustle me out of the waiting room and up a staircase to a rooftop helipad, where a helicopter is powering up. Wind blasts my face as I’m forcefully pulled into it. My backpack is tossed in after me, and we take off before I can even catch my breath. I’ve never even flown in an airplane before, and it’s a shock to feel the helicopter suddenly ascending.

A medic buckled in next to me does first aid on my face as Burlington shrinks away beneath me. From the air, it looks really bad. Scattered across town are fires sending tall plumes of smoke high into the sky. I don’t see any cars moving. The whole town looks like it’s dying.

Within minutes, we land on an airstrip and board a small jet. In the curtained-off section I’m in, it’s just me and two doctors—one male, one female. We take off right away.

Once we reach cruising altitude, they start examining me. They take my temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate, and look into my eyes, ears, and mouth with lighted scopes—basic checkup stuff. They question me during most of the flight, especially about my injury and how it happened. I give a simplified version—I was attacked but managed to run away. They take a detailed medical history. Mostly I’m answering “no” to a long checklist of health problems I never had. They ask me about my family, schooling, community, and work. My answers are straightforward, but I keep quiet about my paranormal experiences.

The whole process makes me uncomfortable. I try not to let my nerves show, but when they ask about The Friends, I become defensive. I know it’s stupid–I’m the only one left. But The Friends lived off the grid. I was delivered by Dorothy at home and never even had a Social Security number. It feels like the government is shining a spotlight on our whole community. Earlier, my blood was examined under microscopes, and now everything about me and my upbringing is being picked apart.

They take notes, and my answers are audio-recorded. The questions only stop when someone comes by with a tray of food and a drink. It’s some kind of microwaved attempt at curry with a yellowish mush on white rice. But it’s the first hot food I’ve had in days, and I eat everything without paying too much attention to what it is.

The two doctors do their best to act with professional courtesy and treat me well, but I feel their tension as they study me. Neither of them is visibly sick, yet I sense they’re infected and know it. They’re desperate. And their desperation is partly directed toward me. I sense what they’re thinking—Why this kid and not me? Why him? Will this kid provide a cure in time?

I’m wondering the same things.

I feel bad for them, but there’s nothing I can do. They’re here to be professionals, and I’m an immune kid they have to process.

After they finish the interview, a grim-looking guy in his thirties comes through a curtain at the back of the plane. He must be a government lawyer because everything he says sounds so carefully worded. He asks me to sign a nondisclosure agreement, warning me that even though I’m a minor, everything I sign is legally binding, due to martial law. After he gets my signature, he tells me I’m being taken to a secure facility at the University of Arizona in Tucson, set up for people with immunity. They’ll brief me about a special program if my test results hold up. If I decide to participate, there’ll be more documents to sign.

When he’s done, I finally have time to collect my thoughts as I stare out the window. It’s actually really peaceful. From this height, there’s no sign of the plague, just an ocean of clouds beneath us.

Before long, I overhear one of the doctors on a phone near the cockpit. She’s nearly whispering, but my hearing is really sensitive. At first, it’s just technical stuff like my blood pressure and a description of the injury to my face. But then there’s a pause like she’s thinking about what to say next. She’s being asked something important.

“He’s remarkably calm, given what he’s been through—he’s alert, intelligent, and well-mannered and . . . Mmm hmm . . . Yes, Doctor Miller, as far as I can tell from our preliminary checkup, he’s in perfect physical health. Yes . . . Yes, as far as his mental health, he gave no outward signs of trauma–at least no obvious PTSD symptoms, and he spoke in complete sentences and gave appropriate, well-organized responses to everything we asked . . . Mmm hmm . . . Yes, doctor, I found him quite personable and cooperative . . .”

The seatbelt light chimes on, and the doctor returns to her seat.

As we descend through the clouds, and the city of Tucson expands below us, my heart starts racing. I sense a shock is approaching, but I have no idea what it’s about. In the hands of these professionals, I’m probably safer than I’ve been in weeks. It’s not about the plane crashing.

No, it’s a person I’m going to meet. Someone who’s just been told about my arrival.

I sense a powerful mind scanning the sky like a searchlight. The sensation lasts only a second or two before I lose track of it. Perhaps whoever it is thought of me briefly, and now their attention is onto something else.

As soon as we touch down and the plane rolls to a stop, the hatch opens, and the doctors usher me out.

I’m shocked by the sun’s intensity and the dryness of the air. It’s so different from the overcast, humid weather I’d left in Vermont. Nearby, another helicopter touches down. I stand on the tarmac in the desert sun for a few seconds before I’m hustled into the copter, and we’re airborne again.

Something obvious finally occurs to me.

Their efforts to get me to this facility are over the top. It must mean immunity is extremely rare.

Our headsets allow us to communicate over the rotors’ noise, so I ask the doctors a question.

“How many people with immunity have you found?”

There’s an uncomfortable pause as they exchange a nervous glance. Eventually, the female doctor answers me.

“You’ll get a full briefing after we arrive and run more tests,” she responds. “If the initial blood work holds up . . . you’ll be number two.”

“Two?” I can’t believe I’m hearing her right.

“We’re hoping to find more,” she adds. “There are facilities all over the country designated for testing people.”

I’m waiting for her to tell me more, but she turns her attention out the side window, perhaps to avoid any more questions. She was uncomfortable telling me what little she did, so I decide not to ask anything else until we get there.

We land on a helipad at the top of a large building. As the rotors slow, and we get out of the windblast area, a lean woman in her sixties with dark hair and intelligent eyes approaches. She smiles and extends her hand.

“Hello, Tommy. I’m Dr. Rachel Miller, but please just call me Rachel.”

She’s carefully informal and friendly, but I can feel her studying me closely. The others keep a respectful distance from us, and she seems to be in charge, at least of me. I like her immediately. Something about her reminds me of Dorothy. It’s her confidence or her sense of dignity, maybe. She takes me by the arm like an old friend, and I feel looked after, carried along by her quiet authority. We make our way down a flight of stairs to a bank of elevators.

“Tommy, we need to trouble you for another blood sample and to run a couple of scans,” she says, “but I’ll be with you throughout. Did they feed you on the plane?”

I nod.

“Good,” she replies. “But while we’re going through these few procedures, I want you to tell me your favorite foods. I’ll make a list, and we’ll bring them to you a little later this afternoon. Once we’ve completed the scans, we’ll do a brief orientation and tour the facilities. Finally, we’ll end up at your living quarters, where I’ll introduce you to your roommate, Kyle. He’s nineteen, just a few years older than you. I’m sure you’ll like him. He’s excited to meet you.”

I’m not sure why, but I pick up a sense of forced cheerfulness as she tells me about Kyle. We step out of the elevator, and I follow her down a hallway and into her office.

“Is Kyle the other person with immunity?”

“Yes,” she says, giving me a guarded look. I sense she’s hiding things, but it doesn’t feel sneaky, more like hiding things is just part of her job. She gestures toward a chair and sits across from me as a lab tech draws another blood sample.

“You and Kyle will be working together closely. And you’re going to be roommates, so you can get to know each other.”

“What’ll we be working on?”

“Well, that’s getting a bit ahead of the orientation, but tell you what,” she says, “I’m going to put a hold on your scans till later today, and we’ll go right into it. That way, you’ll know what’s going on. How’s that?”

I can tell she’s trying to win my trust, but I sense her goodwill. I’d spent the last few weeks tending to the dying and then on my own, so it’s a relief to have someone taking care of me for a change.

“Thanks,” I say.

The lab tech applies a small bandage to my arm, and then quickly disappears into the hallway.

“Have you ever heard of Biosphere 2?” Rachel asks.

“No, I haven’t.”

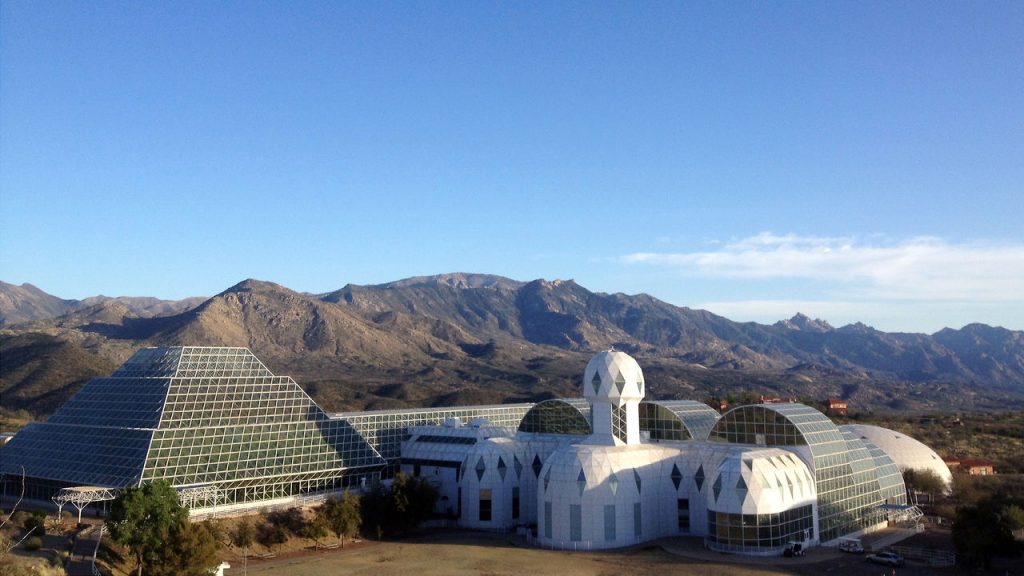

“About thirty-five miles from here, in Oracle, Arizona, is a facility now called Biosphere 3. It was originally built back in the late nineteen-eighties. Until recently, it was called Biosphere 2. The idea is that the Earth is Biosphere 1, and Biosphere 2 is the second complete ecosystem that can support human life. But since we’re upgrading it with the latest technology, we’ve rebranded it Biosphere 3.”

Rachel rotates the monitor on her desk so I can see it. She projects images of Biosphere 3—how it looked originally, and how it’ll look when the refurbishment is finished. It’s this huge, complex structure in the desert. A series of domes and wide pyramids made of metal struts and glass triangles, almost like a computer-generated wireframe, only it’s real.

“The original foundation was built with a stainless-steel liner, enabling it to seal up as tight as a spacecraft,” Rachel continues.

A series of interior images appear on the monitor.

“Inside are biomes—a tropical rainforest, an ocean, a desert, a savannah, an agricultural area, and a human habitat. As you can see, the facility is spacious, over three acres. To be independent of any power grid, we’ve built an extensive array of solar panels in the desert around the main structure. Ten megawatts of autonomous power. The latest robotics will take care of outside maintenance and are currently being programmed to do routine tasks within.

“Once sealed, the biosphere will sustain an atmosphere with optimal levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide. It’s designed to function as a self-contained ecosystem, able to recycle water and produce all the food needed for a community of up to sixteen people, whom we call biospherians. In the first experiment in 1991, only eight biospherians were sealed inside, but we’ve figured out ways to increase its carrying capacity.”

Suddenly, what she’s saying hits me. I thought my immunity might lead to a bunch of medical tests to figure out why. But now I realize that something much stranger is going on.

“And I’m going to be one of the sixteen people sealed inside?”

My question derails her technical pitch. It’s like she forgot she’s dealing with a fifteen-year-old kid. Rachel looks at me with tender concern.

“Tommy,” she says gently, “We won’t seal you in anywhere unless you’re willing. There’s no easy way to say this, but you need to know certain grim facts about our situation. This pandemic is a potential extinction-level event. Unless we find a cure soon, which is highly unlikely, in a few months, the Earth will depopulate. Industrial facilities requiring human maintenance will deteriorate, spilling all kinds of toxins into the environment. It takes a couple of years to properly decommission a nuclear power plant. Once the power grid goes down, the cooling and pumping machinery will be kept up by diesel generators until they run out of fuel. Then they will go critical and melt down. The Earth’s atmosphere will be poisoned for many years with genetically damaging levels of radioactivity. The only place where you or anyone can survive is in the biosphere. And we need you to survive, Tommy . . . If you were my son, I’d want you to be there.”

I can almost see my mom standing behind her, willing me to accept the task before me. She’s gently coaxing me to trust this woman I’ve only just met with my safety, my life. I’m touched by Rachel’s concern, but not sure how to show her this.

“Thanks, Rachel,” I nod quietly, overcome for a moment. “I’m grateful for the chance. I want to help.”

“I’m so glad, Tommy. We’re all working to make the biosphere succeed, but the demands on you and Kyle will be tremendous. It’s too much to ask of someone your age, but we don’t have a choice. Your life will be difficult, and it will remain that way, but you will be serving as great a purpose as any human being could possibly serve.

“Beyond protecting you and your rare immunity, we need to preserve the genetic potential for humans and other terrestrial life to continue. The future seeds of the human species—uninfected embryos and sperm from a genetically diverse set of people—will be stored in cryogenic suspension inside the biosphere. So in addition to the biospherians, animals, and plants, there’ll be extensive banks of seeds and genetic samples of numerous species.”

“Like Noah’s Ark?” I ask.

Rachel gives me an appraising look. I can tell she’s a science type who’s allergic to religion. She’s wondering if I’m a fundamentalist Christian or something.

“Don’t worry,” I add, “I’m not super religious or anything.”

Her eyes widen momentarily as she realizes how much I read from her expression.

“Yes,” she continues, “it actually is like a high-tech version of Noah’s Ark. Others have made the comparison. Of course, you won’t have two of every animal. But the biosphere will have insects, fish, pygmy goats, chickens, and six monkey-like primates called galagos.

“And Biosphere 3 is like a ship, though more like a stationary spaceship than a seafaring vessel. A remarkable coincidence is that Biosphere 3 is located in Oracle, Arizona, a town named after a 19th Century sailing ship. It’s as if the place was destined to be the site of a great desert ship. The vessel itself, Oracle, was named after a sacred site in Greece with temples dedicated to the twins Apollo and Artemis. People went there during times of danger to consult the cosmos.

“As you can see,” Rachel continues while projecting a video on the monitor, “the biomes are rather beautiful, but beneath them is an industrial basement level called the Technosphere. It’s filled with tunnels, machinery, plumbing, and wiring. One of the original eight biospherians compared the biomes to a miniature Garden of Eden growing on an aircraft carrier. The Technosphere includes storage rooms, workshops, laboratories, cryogenic facilities, and a supercomputing center. As we speak, the mainframe computer, which we call Gaia, is being uploaded with just about every bit of digital information in the public domain.

“The facility is designed to comfortably house, feed, and maintain a breathable atmosphere for a capable group of immune people.”

“A capable group?” I ask. “You mean being immune isn’t enough? What capabilities are you looking for?”

Rachel raises an eyebrow.

“Very perceptive, Tommy,” she says, smiling. “Don’t worry. I’m already certain you’re highly capable. Starting tomorrow, if you sign on to be part of the program, you’ll begin extensive training on how to live in and maintain a biosphere, especially the high-tech agricultural work.

“You’ve already got a great background. I listened to your interview on the plane. I can’t imagine a more perfect upbringing to prepare you for living in a biosphere than growing up in an isolated permaculture community. And your roommate, Kyle, is one of the most capable people any of us have ever met. All I meant by ‘capable’ is, well, suppose we found an immune person who was psychotic? Or what if they were immune to the virus but about to die of another cause?”

Rachel pauses, and slowtime comes over me as I sense a major revelation coming.

“I was planning on going into this later, but the most crucial attribute we’re looking for is the capacity to live in isolation with a tiny group of biospherians. I must be honest with you, Tommy. The outcome for small groups living in isolation—Antarctic explorers, astronauts, cosmonauts, and biospherians—is not good. Human beings are social animals meant to live in open communities of at least a few dozen people, but we don’t have that capacity. Biosphere 2 was originally designed to support eight people. With the upgrades, we think we can double that capacity. However, for the biosphere to succeed, we need fertile, immune women.

“To be frank, the isolation factor is troubling. Even though they’d been part of the same community for years, the original team of biospherians developed bitter conflicts. Like most cases of communal isolation, they factionalized into two opposing groups.

“My job with the Biosphere 3 project is to prepare biospherians for the social isolation they will endure. This is quite a challenge because although technology has advanced enormously in the decades since Biosphere 2, human nature hasn’t. Tommy—”

Rachel gives me a serious look.

“I’ve known you for less than an hour, but I can tell you’re an asset to this endeavor. Your upbringing in an isolated community, the volunteer work you did at the hospice, your obvious ability to tune into others—as far as I’m concerned, you have the most crucial capabilities we’re looking for.”

Slowtime allows me to study everything Rachel says. It’s as if her intelligence is boosting my perception. I see what’s beneath her statements. Although I tend to hold back with people I’ve just met, something tells me to show her I’m picking up on what she didn’t say.

“You say you’ve been looking for those capabilities. You mean—you didn’t find them in Kyle?”

She’s startled but quickly recovers her poise.

“Kyle has great leadership skills and absolutely crucial scientific and technical abilities. But like many technical people, he doesn’t have the—,” she hesitates, “your emotional range, let alone the empathic ability you’ve shown me already. Advanced technical thinking and high emotional sensitivity in the same person are a rare combination.

“But I’d rather you form your own impression of Kyle. And I don’t mean to imply any deficiency in him. He’s by no means a science geek or someone dry and technical. He has high social skills, but of a different sort than yours. Most people here find him highly charismatic.”

Rachel pauses to read something on a computer screen.

“Congratulations, your blood work confirms the initial tests. You’re officially immune to the virus. And now I think we should alter our plans once more. I’ll take you straight to your living quarters to introduce you to Kyle so he can complete your briefing. It will be more valuable for you to spend time with him than anyone who won’t be in the biosphere.”

Rachel gets up and beckons me to follow. We step into an elevator. The doors close, and the moment stretches. As we descend to the dorm level, my heart starts racing again and I sense the shock I anticipated on the plane is about to happen.

We step out to enter a long, stark hallway. As we walk by a series of closed doors, I sense the dorm rooms behind them are empty and lifeless.

Rachel stops at a door at the end of the hall and knocks. At her third knock, the door swings open, and a tall, athletic-looking guy with piercing gray eyes stands before me. There’s a split second of surprise when he sees me. Maybe it’s because of my huge black eye. Before I can read any further into it, he gives me a bright smile and shakes my hand in a powerful grip.

“Tommy! I’m Kyle. Great to meet you. Welcome!” he gestures me into the room.

“Thanks, Kyle,” says Rachel. “I’ll leave you two to get acquainted.”

Kyle waves, and so do I before he closes the door behind us.

“Rachel probably explained why they’re not giving us separate rooms or much living space?”

I nod and take a deep breath, trying to relax, but slowtime has me feeling too out of phase to speak. My instincts are picking up things about Kyle that my mind can’t grasp, so I try to tap into what my body senses. Waves of nervousness pass through me as my heartbeat quickens again.

Kyle is, like Rachel said, charismatic. He’s friendly and cheerful, yet something about him is different from anyone I’ve ever met. His sleeveless shirt shows he’s got crazy muscle definition—like an Olympic athlete. But looks aside, I can’t catch hold of what makes him so unusual.

I sense no ill intent from him. Quite the opposite. He seems to like me and is happy I’m here, but that’s all I can read from him.

He doesn’t seem phased by my silence and quickly fills in the gaps.

“This one’s yours,” he says, giving the bed along the left wall a friendly pat. The room is small and perfectly clean. My pack is resting on top of a dresser. Kyle opens an artificially wood-grained refrigerator and passes me a bottle of cold water.

“Thanks,” I finally say.

It’s the first word I’ve spoken to him, and I had to force myself out of the more extreme depths of slowtime to get it out.

“We’re under orders not to drink a drop of tap water,” says Kyle, “but there’s bottled water for us everywhere. Are you hungry? They’ll have dinner for us in a couple of hours, but we can get snacks from the cafeteria.”

“No thanks, I’m fine. They fed me on the plane,” I reply.

“That’s quite a shiner,” he nods at my black eye. “Are you in any pain? Want an ice pack?”

“Ah, no thanks, I’m fine. It probably looks worse than it feels.”

Kyle reaches into the fridge for another bottle of water.

“In case you want to rest it on your face, the cold will help.”

“Thanks.” I take the bottle to be polite.

“I was told you arrived safely, but they neglected to say anything about the injury. You were attacked?”

As casually as I can, I give him the version of the assault I told on the plane. Of course, it’s at least half a lie considering how much I’m leaving out.

Kyle studies me.

He knows I’m being deceptive.

I’m ready for him to call me on it, but he takes it in stride.

“I wish I could’ve been there,” he says enthusiastically. “I’ve been training in Brazilian jiu-jitsu and other martial arts since I was a child. Sorry you had to go through that, but I’m glad you were able to escape. If you’re fast enough to get away from an attacker, that’s often the best course of action.”

The martial arts training explains a lot. Kyle’s eyes and movements are almost cat-like. I sense some version of quicktime might be his normal state. He’s hyper-alert, like a Navy Seal who might be called into action at any moment. I’ve no doubt he could’ve demolished my scruffy attacker.

“I wish you would’ve been there too,” I offer, trying to cover my anxiety about being caught in a lie.

Kyle smiles, pleased by my compliment.

“If you’d like to learn martial arts, I’d be happy to teach you. Exercise breaks are built into our schedule, and it’d be great to train with someone again. We’re not likely to need such skills in a biosphere, but it’s a great mind-body discipline and way to keep in shape.”

“Thanks, I’d like that.”

The words have barely left my mouth, and I feel guilty. The Friends were committed to nonviolence. For me, it’s not just my upbringing, but what I feel and believe. And now I’ve agreed to martial arts training.

“I understand you had to hike about seventy miles to get to the testing facility.”

“Something like that.”

“I bet you’d like a shower.”

“Oh, I’d love one. But is there time?”

“Of course,” says Kyle cheerfully. “I’m under orders to make you feel welcome, and that takes precedence over anything else today. Once you get settled, though, you should expect our time to be tightly scheduled.

“There are clean towels and toiletries in the bathroom,” he points to a door at the back of the dorm. “They stock this dorm like a hotel room and clean it while we’re away. They’re not trying to spoil us—it’s because every minute of our time is needed for training. But Rachel put everything on hold today, so this feels like a vacation.”

As Kyle speaks, I go through my pack to find clean clothes. His cheerful tone seems like an act. For some reason, he’s playing a role that has nothing to do with who he really is. Like he’s in an ad for the University of Arizona portraying the perfect college roommate from the perspective of parents. This feels like a vacation sounded completely fake. The most obvious thing about Kyle is that he’s the type that’s always on alert and ready for action. I doubt he even knows what vacation feels like.

Kyle sees the old clothes in my hands and points toward a closet.

“Forgot to tell you, a set of new clothes was delivered for you when they brought in the bed. You’ll find more in your dresser.”

I put the old clothes back in my pack and quickly check out the drawers and closet, taking a few things to wear after the shower. There are high-quality tracksuits and casual clothes, exactly my size, along with cool-looking running shoes.

“Let me show you something about the shower. It’s tricky, and I scalded myself before I figured it out.”

Kyle speaks in the same perfect college-roommate tone, but he gestures toward the bathroom with eyes that look deadly serious and commanding.

I use the mirror to track him as he follows me into the bathroom. In a clever move of faked clumsiness, he bumps the bathroom door, causing it to shut behind him.

My heart is pounding. Adrenaline pumps through me like I’m about to be attacked.

He turns the shower on high, puts his hand on my shoulder, and leans in to whisper in my ear.

“If it seems like I’m acting, it’s because I am. Everything we do and say here is being monitored. Cameras and microphones are nearly everywhere, and we’re being studied and evaluated constantly. Be careful what you say to Dr. Miller. She’s the one who could disqualify either of us. Don’t ever complain or look worried or stressed about anything. Just follow my lead. Your life depends on showing them you’ve got what it takes to fulfill this mission. I’ll tell you more next time there’s a chance to evade the surveillance.”

Kyle turns away before I can say anything.

“Enjoy your shower!” he calls out in a loud, cheerful voice as he closes the bathroom door on his way out.