Parallel Journeys—-sample, Chapter One

January 6, 2014

The Surreal Zone

9,010 Views

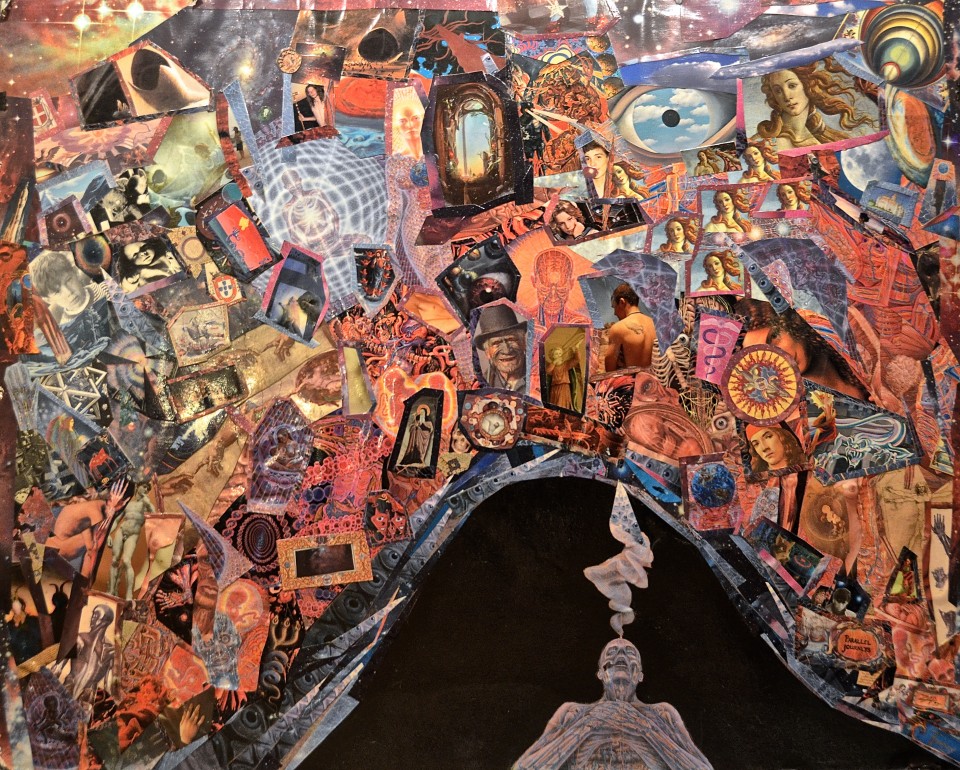

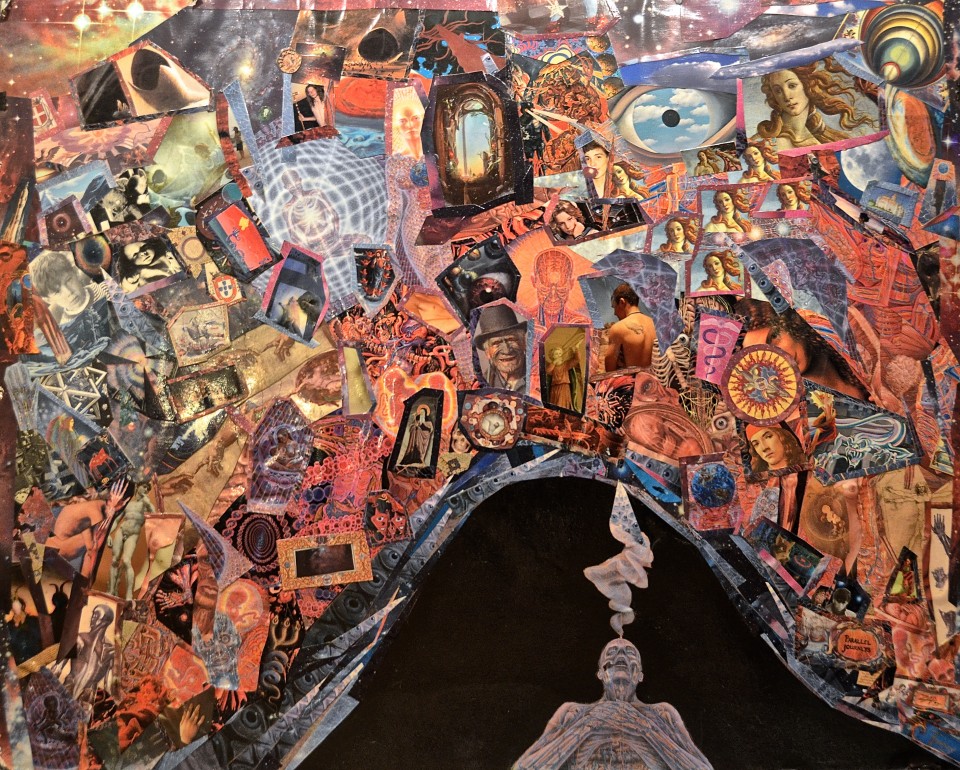

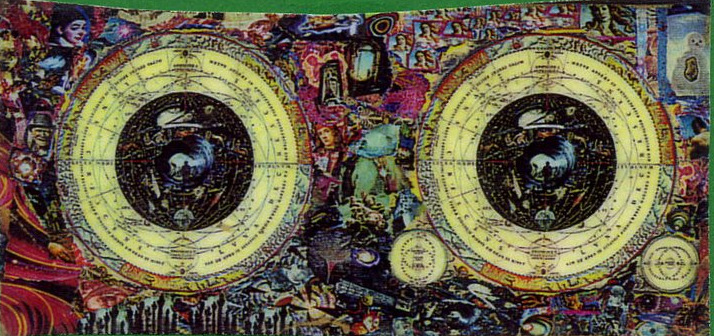

cover image: Interdimensional Passport, 1997, paper and gel medium on plywood by Jonathan Zap

-

-

Interdimensional Traveler Logo, copyright Jonathan Zap, 2010

Parallel Journeys © 2015, Jonathan Zap

-

-

Parallel Journeys collage, copyright 1996, Jonathan Zap, paper, gel medium and varnish on foam core poster board(my friend Alex Grey has seen the collage and generously approved my use of numerous images from his book, Sacred Mirrors)

This revision of Chapter One posted on 2/17/17

Chapter I

Andrew’s Journal, March 23rd

Occurrences of high strangeness, like the one that just happened tonight, have been the key turning points of my life. Until a few months ago, I was a photojournalist and earned a living writing about subcultures. Although that sounds like a profession that should prepare you for writing about anything, when it comes to the anomalous aspects of my own life, I’ve struggled to find both will and words to render them into a narrative.

An uncanny occurrence, past a certain level of strangeness, can be a charged, slippery, squirming thing as hard to grasp as an electric eel tossed down an elevator shaft. When I try to catch such an experience in a net of words, it feels like the holes in the net are too large and the eel just slips through.

And yet, especially after what happened last night, some inner urgency insists that I try again.

All witnesses disappear sooner or later, but if I can make a worthwhile record of my experience, even if it is only a string of zeros and ones lurking somewhere in the interstices of the web, I have a feeling that at least a few people will find it.

“Seek and you shall find,” sayeth the web. You cast a lure out into its depths, a lure you make with key words, and out of some obscure crevice comes just what you were looking for—squirming and alive on your screen.

I’ve learned that anything can happen to me at any moment, but the sequence of binary numbers I cast out into the web will keep lurking out there long after I’m gone. Perhaps my account here will be someone else’s electric eel to be coaxed out of the obscure depths of cyberspace through some unexpected link or search return. If this is how you have found these words, I hope their slippery meaning is easier for you to grasp than it has been for me.

Although I may be only twenty-six years old, and people say I look almost exactly as I did at nineteen, I am filled with a sense of the impermanence of life, and at the moment feel only tenuously connected to it.

A car accident when I was twelve killed my parents and brought me past the threshold of death and back. After months in the hospital I recovered my health, but was left permanently disfigured by burns, though none of them are apparent when I wear clothing. The placement of my burns, what I came to think of as my “fireskin,” seems weirdly appropriate in a way. Unless I take off my clothes, I look perfectly normal. But underneath my clothing is another version of me, a fireskinned version.

I’ve learned to maintain these two versions of myself on multiple levels. The clothed version has functioned well in society. I graduated from college when I was twenty and then had an unusual degree of success as a photojournalist. But underneath the clothing and successful career, the fireskinned version of me has had intense paranormal experiences, experiences that, like my scarred flesh, I’ve kept carefully hidden.

But there is a guilty anxiety that comes with keeping up these two versions. I feel like someone running an illegal business that has two sets of books. I have a public ledger that isn’t exactly false, but that omits the most significant events of my life, and I have a secret one that I have kept hidden away in the deepest vaults of memory.

There’s a line in the first of the Lord of the Rings movies that’s always resonated with me: “Keep it secret, keep it safe.” Now it feels like I am writing out my passwords, social security number and all my other keep-it-secret- keep-it-safe stuff on a page for anyone to find. That’s why the palms of my hands are sweating as my fingers hover indecisively above the keyboard.

I’ve always been an intensely private person—a loner, an introvert, and a careful listener who often attracts the secrets of others. After a lifetime of guarding secrets, it’s hard to spill them out into a public journal. And the secrets I am divulging are not just mine, but include a few people very close to me.

Even though my intention is to disclose everything, I don’t want to draw a red circle around anyone. So I am omitting last names, some specific place names and a few minor details for privacy reasons.

01101101 01101111 01110010 01100101 00100000 01110100 01101111 00100000 01110011 01100101 01100101 00100000 01101111 01101110 00100000 01110100 01101000 01100101 00100000 01100100 01100001 01110010 01101011 00100000 01110011 01101001 01100100 01100101 00100000 01101111 01100110 00100000 01110010 01100101 01100100 00100000 01100011 01101001 01110010 01100011 01101100 01100101 01110011

For six years, following a lucky break I got just out of college, I viewed life from the perspective of a photojournalist writing about subcultures. The journalistic instincts that got wired into me during those years are another reason I feel so nervous about writing this account.

I took my work seriously and strove to conduct myself with integrity. Anyone with sense realizes that there is no such thing as perfect objectivity, and one human being observing other human beings is about as subjective as it gets. But it’s the responsibility of a journalist to strive for some degree of objectivity.

When you sense the limits of your impartiality, it’s unethical if you don’t acknowledge them to yourself and to readers. A number of my published articles include disclosures of biases I had about subcultures I observed. I think that any journalist who has active biases about a subject they are writing about and who does not disclose them is inauthentic at best, and very likely a charlatan.

My photojournalism career began by spending months immersed in the lives of obsessive online gamers. Then for half a year I lived in my camper van near an Amish community, exploring their world. The contrast of these first two cultures was extreme, and I soon realized that there was some way in which I needed that extremity. The online gamers and the Amish lived in different dimensions, and this allowed me to feel like an interdimensional traveler experiencing alternate realities.

Wanting to keep the extreme contrast going, after I finished my time with the Amish I spent the next several months immersed in the vampire subculture of a few large cities.

Although I was always aware of myself as an outsider and observer, I had strong personal reactions to each of these worlds. I realized the impossibility of overcoming the subjectivity of that, but I never submitted an article until I felt I had reached some degree of objectivity.

But when it comes to my own experiences, and what amounts to a subculture of one writing about himself, I have to admit that I’m never going to reach the degree of objectivity that will satisfy my journalistic instincts. And yet, as subjective as my testimony might be, I sense that it will have value for a few other strange people who somehow or another will find my words. It is for these people, wherever they might be in space and time, that I am writing. I feel an urgency about this task, a need to get this written and cast out into cyberspace. None of us knows how long we will be here, and now more than ever, I feel the fragility of my bond to this plane of reality. I sense that I could get called away at anytime, and I’m willing to be drawn wherever I am needed to go.

01100001 01110010 01100101 00100000 01111001 01101111 01110101 00100000 01110111 01101001 01101100 01101100 01101001 01101110 01100111 00100000 01110100 01101111 00100000 01100010 01100101 00100000 01100100 01110010 01100001 0111011101101110 00111111

Sitting here in the darkened interior of my camper van, the screen of my laptop glowing expectantly before me, I feel those few other people reading these words and pressing me to continue. I sense that they are also leading double lives and have had parallel anomalous experiences.

I am catching inner glimpses of some of these people, though their faces seem to be just past the edge of my peripheral vision. I see the shadowed silhouette of an adolescent male, time and perception flowing through him in a way that sets him apart. There is a fiercely intelligent middle-aged woman with dark hair, an aura of occult experience crackling about her. Sitting forward in a chair is an androgynous young woman. She is living close to the edge and seems poised for physical action. And there are a few others who I sense, but can’t envision. They appear to be shrouded by mysteries that distort my vision of them like heat rippling off hot asphalt. I can’t quite make out who they are, but I feel their presence, the force of their unique personalities and lives, and sense that they will find the meanings and patterns in my account that currently elude me.

And then there is another reader, I hope, one who I know intimately but who is also hidden from my sight. For the last few months I’ve been undergoing a strange and painful separation from the strongest connection I’ve made to another human being since I lost my parents— my best friend Alex, who was also my traveling partner for three years. For reasons I am still struggling to understand, Alex decided that we should permanently separate and has broken off all communication with me.

Alex was the one person I confided my deepest secrets to. I also carry within me the strangely parallel secrets he confessed to me. And this is another reason motivating me to write this journal. I have new secrets now, secrets that I feel have value to at least a few others, but there is no one presently in my life I can share them with.

I feel a need to cast these secrets, like messages in a bottle, out into the turbulent sea of zeros and ones enveloping this planet.

00100000 01100100 01101001 01100100 00100000 01110100 01101000 01100101 01111001 00100000 01100110 01101001 01101110 01100100 00100000 01111001 01101111 01110101 00100000 01101111 01110010 00100000 01100100 01101001 01100100 00100000 01111001 01101111 01110101 00100000 01100110 01101001 01101110 01100100 00100000 01110100 01101000 01100101 01101101 00111111

When Alex disconnected from me I was between assignments. I had been staying at the Piñon Mesa Wildlife Refuge in Colorado, a small community of idealistic young people dedicated to rescuing big cats from guaranteed hunts and other abusive situations. The refuge was distinctly its own subculture, successfully living up to its aims with authenticity and heart, and I expected it would be my next subject.

For me, writing about a subculture requires near total immersion. Whenever I found a subculture that intrigued me, it was a little bit like falling in love. It wasn’t as unreliable as infatuation, I didn’t idealize these subcultures or look to merge with them romantically, but there was always a feeling of heartfelt commitment, a sense that I owed them the best story I could tell about what they were. I took that commitment seriously and devoted myself to it, and once I began reporting on a subculture, I stayed with it until it was done to the best of my abilities.

That had been working for me for six years, but Alex’s sudden and unexpected rejection made journalistic immersion impossible and I was forced to put my career on hold.

I had enough money saved to get by for a while, and living out of a camper van is pretty cheap, but I needed something to do, something with a moral purpose that could pull me out of the inner chaos. So instead of writing about the Piñon Mesa Wildlife Refuge, I became a volunteer fundraiser for them. They had a small crew of canvassers working for them locally. With my camper van and traveling lifestyle, I could serve as a nomadic fundraiser.

Even though they prepared me for it as best they could, I didn’t get the psychological stress of door-to-door fundraising until I started doing it on my own. Danny, their master canvasser who took me on a one-night “skill share” canvass, cheerfully called it “annoying people in the privacy of their own homes.” I stood next to Danny as he endured rejection, and sometimes extreme rudeness from people, and somehow he took it all with good humor, even chuckling when one person slammed a door in his face. Danny warned me not to take any reactions personally, “Rudeness and rejection just come with the territory,” he said.

I thought I understood that, but fundraising door to door by myself night after night has not always found me as emotionally impervious as Danny was during the skill share. Canvassing is stressful, but it would be absurd for me to complain about it since it’s something I’m choosing to do and it’s also been the main thing keeping me together.

And sometimes canvassing provides pleasant interactions with people. Many nights someone will invite me in to drink tea or a beer, or even smoke some weed with them, and usually that’s followed by the writing of a check, sometimes a generous one. These more personal encounters relieve the loneliness of nomadic canvassing.

01110111 01101000 01100101 01110010 01100101 00100000 01100001 01110010 01100101 00100000 01111001 01101111 01110101 00100000 01101000 01100101 01100001 01100100 01101001 01101110 01100111 00111111

Earlier this evening, when I forced myself to step out of my camper with my clipboard, I found that a thick fog had settled over Seattle. The streets seemed only half-realized, as if they were fading into memory. It was the stagnant, disassociating fog of a bankrupt dot-com executive lying etherized upon a table.

I found myself in canvassing autopilot mode, going through the motions, scarcely paying attention, relieved that few people were coming to the door to answer my knock. My mind kept drifting back to the strange and disturbing dreams, almost nightmares, I’ve been having about Alex. Images of Alex, alone and terrified, in a dark, abandoned city were flickering in my mind as I opened the chain-link gate of an infinitely-bland, early-seventies ranch house. It wasn’t until I knocked that I registered all the classic visual clues that I had disturbed the home of a highly conservative, elderly person. The stoop was covered in threadbare AstroTurf, and windowsill shelves held dusty knick-knacks of the sort where a ceramic Eiffel Tower might stand next to a puffy, large-eyed plastic child whose outspread arms held a little placard that read “I love you this much Grandma!”

The door rattled and then opened a couple of inches, a brass security chain pulled taut, and through this gap, peered a gaunt, elderly woman in a shabby dress. Her eyes were clouded with cataracts, and she gazed at me with a look of uncomprehending irritability that teetered right at the edge of senile paranoia. There was what looked like a hearing aid in one ear, but something told me that the batteries had been dead for a long time.

Her aged face was ground zero for a déjà vu shockwave that staggered my mind and left me dumbfounded for a moment. Then autopilot clicked in and I managed to deliver the opening line of my rap,

“Sorry to bother you, my name is Andrew and I’m doing a fundraiser for the Piñon Mesa Wildlife Refuge—“

“Mr. Anderson from the what?”

“From the Piñon Mesa Wildlife Refuge.”

“I don’t need any wildlife. I’m on a fixed income.”

But I was no longer listening to what she was saying, because now I knew with absolute certainty where I had seen this old woman before.

The first time was when I was nine-years old and was with my mom as we waited in line in a tiny Manhattan supermarket. I remembered her because she had a dozen containers of cottage cheese lined up on the checkout conveyor belt and on top of each one was a torn-out newspaper coupon. Most were torn with very uneven edges, and I realized she must have scavenged discarded newspapers to get them all. I hated cottage cheese and couldn’t imagine what someone would want with so much of it. And she had this proud, defiant look, like she was daring the cashier to object to her cottage cheese hording.

Then, just a few weeks later, we were in Maryland visiting family, and I was walking down the aisle of a much larger supermarket with my cousins and I saw the same supermarket lady wearing the same floral dress I had seen her in a few weeks before in Manhattan. As if she had been designed to renact this one ritual, she stood defiantly before a dozen tattered coupon-topped cottage cheese containers lined up on the conveyor belt of a checkout station, her stern expression starkly illuminated by florescent light.

I had this shattering feeling that I had seen something I wasn’t supposed to, a flaw in a gigantic deception, and I was terrified about what would happen if anyone knew that I had caught on.

I quickly looked away from her and tried to cover my shock. I was afraid that if the supermarket lady knew that I knew, she would emit a high-pitched, piercing scream and that all the other simulated people would stop what they were doing and surround me, engulf me.

In the days after the supermarket incident, I had a gnawing anxiety that many people, and perhaps all people, were “extras”—people somehow contrived to fill in crowd scenes, to take up most of the empty space on subway trains, to mutely walk down sidewalks holding lumpy plastic shopping bags in the hot sun. When I looked at their eyes, looked closely, I had a feeling that there was no one there, that I was just seeing glass doll’s eyes, cleverly made to look bloodshot, and to scan and blink like real eyes. If you didn’t look closely, the extras looked real, but if you examined any one of them minutely, you could see that it was actually a mechanical simulacrum created by advanced alien technology.

The fear that I lived in a world of extras even extended to my family. I wanted to ask my mom how I would know if she and my dad were really themselves and not precise replicas created by aliens. At first I hesitated to ask because I feared some terrible retribution if I called out the great deception. But then I realized no retribution was necessary. I imagined asking my mom the question and having her smile and reply, “Yes dear, of course we are replicas. Isn’t it obvious?” I thought that would be the most horrifying outcome, but then I imagined asking her the same question and her answering, “No, of course not, whatever gave you that crazy idea?” But she would have this ever-so-slightly crooked smile and glint in her eyes that would tell me that she was lying, and that she knew that we both knew it was a lie.

There were too many terrifying possibilities. I never did ask, but this was what was tormenting me in the days before the fatal car accident. After I regained consciousness in the hospital, and was told that my parents didn’t make it, paranoia was replaced by raw grief. I knew I was mourning for them and not any replica, and when I remembered the crazy thoughts I had in the days before the accident it was with bitter regret and guilt.

Apparently, this type of paranoia is fairly common. There’s even a name for this condition—Capgras Syndrome. But even though I have long since outgrown this childhood paranoia, I’ve never entirely shaken the feeling that things are not quite as they are trying to seem.

And then, when the door of this house opened and I saw, standing right in front of me, the very same supermarket lady, still wearing the same frowsy, floral-patterned dress she had been wearing in the Manhattan supermarket, the almost forgotten paranoia of childhood came rushing back.

Autopilot still allowed me to deliver the opening lines of my rap, but then shock seemed to paralyze my ability to speak. The great deception I had feared as a child now seemed to be staring me right in the face and I had this sickening feeling that she knew that I knew.

As I stared at her, her facade fell away. The senile scowl disappeared along with the cataracts, and there was a high-pitched ringing or humming in my ears. I couldn’t quite hear what was said to me, but I knew I had been invited into the house. In a state of shocked compliance, I stepped into a living room whose only illumination was a black-and-white television with a test pattern mandala glowing on the screen.

And then I had that acutely embarrassing sensation you get when you realize you have been way off in guessing someone’s age, or perhaps have even mistaken their gender, because now I could see that the old woman was not actually the supermarket lady, or even an old woman. The hair that looked white was actually light blonde, and what had seemed like wrinkles were actually just a mottling of shadows made by the screen door. What looked like cataracts were reflections from eyes that were large and grey, almost silver. They belonged to a sorrowful, pale boy wearing a white button-down shirt, narrow dark tie and grey trousers. His style of dress seemed to be that of an English schoolboy from an earlier era. His eyes were sad and intelligent and seemed to be observing me carefully. I felt embarrassed and confused.

I assumed that walking around poorly-lit streets in the fog had played a terrible trick on my vision. I tried to bring autopilot back on line, and in a rather stilted way asked,

“Are you interested in helping endangered wildlife?”

“Yes, I am,” replied the boy. He had a slight British accent and spoke in a manner that was confident, formally polite, but also deeply sincere and humble. His tone and answer were so unexpected, I wasn’t sure what to say next.

“You are?”

“Yes,” he replied with the identical tone—sincere, confident precision.

“You want to help endangered wildlife?” His manner unsettled me, and I was lapsing into redundancy.

“It’s the main reason I came here.” This last statement puzzled me into another silence. I replayed it slowly in my mind,

It’s-the-main-reason-I-came-here. He sounded so sure of himself, but I couldn’t quite get a handle on what he meant.

“Please,” said the boy as he turned and gracefully, with an elegant old-world manner, motioned for me to follow. We stepped out of the darkened living room and into a long, wide corridor of polished brown marble, magnificently decorated with Persian rugs of deep colors and intricate patterns. Crystal chandeliers glimmered from the high-arched ceilings. There were mirrors and paintings on the walls as well as beautiful cabinets of mahogany and beveled glass that were filled with what appeared to be antique nautical instruments—sextant, astrolabe, ship’s chronometer, globes of various kinds, a complicated apparatus of gears and spheres of precious stone—was it an orrery or a model of some other solar system?

I followed the boy down the long corridor, and into a room that looked like the private study of a nineteenth-century English gentleman. There were floor-to-ceiling bookcases filled with antique hand-bound books with gilt titles and marbleized paper on the covers. There were draperies of wine-dark velvet, and a beautiful chandelier whose faceted crystals were so prismatic that they seemed to be dripping with color. The boy motioned me toward a comfortable chair, while he sat behind a large desk with an elaborately carved oriental dragon motif. On the desk was a single object, an exquisite mechanical clock, a “grand complication,” with numerous hands and dials that showed phases of the sun and moon, and God only knew what else, for this clock had alchemical symbols or glyphs where one expected to see Roman numerals. The clock was housed in a crystal bell that revealed a whirring galaxy of gears, jeweled bearings, and other tiny parts in complicated movement.

“Would you care for something to drink?” The boy gestured toward a small marble-topped serving cabinet on which there were glasses and a crystal decanter of amber liquid. I assumed it contained some costly brandy, and wasn’t sure about the legality of accepting alcohol from a minor. Come to think of it, I wasn’t supposed to enter a home at all on the invitation of a minor. Something had addled my judgment.

“It’s non-alcoholic.” Was this boy reading my mind?

“Well, in that case . . .” He carefully poured me a drink, and handed me a glass tumbler of the amber liquid. It tasted golden, fragrantly herbal, like a mixture of sparkling cider, currants, maple syrup and cinnamon. Its effect was warming, relaxing, enlivening in a way that was more like an elixir than a stimulant. This seemed uncanny, until I remembered that nowadays, exotic, herbal concoctions could be found in any corner store. I took another sip of the drink, and put my clipboard filled with animal photographs on the desk.

And then, although the room looked exactly the same, it was like stepping out of a mirror and yet being in a mirror world at the same time. I knew that I had been mesmerized by a beautifully-realized illusion, and although I had awakened inside the illusion, to all my physical senses what I was experiencing felt as solid and stable as ever.

“You’re not who you appear to be.” I said to the boy.

“No, I’m not,” he agreed without hesitation. His tone was somewhat saddened, but not apologetic. I had a déjà-vu-tinged feeling that we already knew each other from past, future and perhaps some other dimension of time.

“Can you tell me who you are?”

“I don’t think so.”

“You don’t think so?”

“I would like to, but . . . there is a force that resists certain choices.”

“What sort of force is that?”

“Well . . .” the boy paused, and looked away for a long moment.

“I suspect that knowing who I am right now might distract you from your life mission, from what you need to do next . . .’ The boy studied me intently. “There is a strong current of time running through you, a current that will pull you somewhere very soon. I must not interfere with it . . .”

“Pulling me where?”

“I don’t know exactly, but I can feel that you are in the grips of a painful obsession. You are about to get pulled deeper into it, and that needs to happen.”

A vision of Alex slashed across my mind. As if sensing this, the boy raised his eyebrows slightly, his expression inviting me to say more.

“My best friend, Alex, severed ties with me a few months ago. He gave no explanation. It was a terrible shock and I’ve been struggling with it ever since. There’s been no communication from him, but I have this feeling that he’s in danger. And for the last few days I’ve had disturbing dreams about him.”

“Dreams?”

“Yeah, a whole series of them. In all of them I find Alex in a dark, desolate city. I never see anyone there except him and it is always nighttime. In the last dream, Alex had a terrible wound to his left hand and arm which were wrapped up in rag-like bandages. He’s desperate and fearful.”

“What is he fearful of?” asked the boy.

“Of being attacked, I guess. Living alone in a dangerous neighborhood. In his right hand he was clutching an old wooden baseball bat, holding it up like he was fending someone off. I want to do something to help him or protect him, but the dreams never allow me more than a moment of contact. He recognizes me, and I am with him long enough to witness his state of desperation and loneliness, and then the dreams just end. I wake up feeling distraught and desperate to rescue him from something. But I don’t know what to do with those feelings. Alex knows how to get in touch with me. He knows I would be willing to help any way I could. Maybe these dreams reflect my emotional state and have nothing to do with him. For all I know, he’s doing just fine and disrespecting his wishes and getting in touch with him based on dreams I’m having might be a pathetic intrusion.”

The boy had been studying me with silent intensity. When I narrated the dream, I felt that he was not just hearing it, but seeing it with me. When I finished speaking, he closed his eyes.

Time seemed to stand still as I felt him looking into the situation with inner vision.

When he eventually opened his eyes, he gazed at me silently. I sensed that he was compassionately gauging what I was ready to hear.

“I can tell you what I feel, what I sense, but you are the one who is closely linked to Alex. Your inner truth sense is the judge of what I say.”

“Always.” I said, nodding in agreement.

“I feel your dreams are about something that is happening to Alex. But whatever he is going through right now, he doesn’t want you to be part of it. At least not yet. He may not be fully conscious of it, but part of why he is keeping you away is to protect you. He feels that what he is going through would endanger you.

“You are at the verge of a shock —a revelation, a communication, something related to Alex is coming toward you without your having to do anything. Your life mission requires you to be completely present for that. There hasn’t been anything for you to do about what’s going on, but there will be once the shock happens. Other aspects of your life mission or mine would only distract from that.” Another moment of silence as he studied me empathically.

“I sense that our paths will cross again, but right now you are needed for whatever is coming next with Alex.”

The boy stood up, signaling the end of our meeting. I stood up too, and we walked in thoughtful silence down the long corridor of polished brown marble. At one point I glanced to the right and saw the reflection of our moving profiles in a long oval mirror. It was only a glance, but it seemed like the reflection of the boy was different, slightly taller and with long blonde hair. His clothes were different too. I sensed that everything I was seeing was an exquisitely realized illusion and wondered whether the distorted reflection in the mirror was purposeful.

We stepped out into the incongruously shabby living room where the test pattern mandala was still glowing on the black-and-white television.

The boy turned to look at me with his solemn grey eyes. “Blessings to you brother,” he said. There was that déjà vu twinge again, a feeling that I had been in this moment before and that it rippled through past and future. And then . . . there is a slight gap in my memory. I can’t remember what, if anything, I said to him. All I can recall is opening the chain-link gate and walking down the street about half a block. Then I stopped and looked at my clipboard so that I could mark the location of the house on my map. Under the metal clip were a dozen very new–looking hundred-dollar bills. He must have given them to me or placed them there during the brief memory gap.

The darkened Seattle streets were wet and a light, misty rain was falling. Everything was shrouded in mysteries and meanings that felt like they were right at the edge of perception . . .

Questions erupted in my mind like searchlights, trying to pierce the swirling darkness.

What just happened?

I felt myself pulled toward the camper and the need to write this all down . . .

01100001 00100000 01110100 01101000 01110010 01100101 01100001 01100100 00100000 01101111 01100110 00100000 01101111 01101110 01100101 01110011 00100000 01100001 01101110 01100100 00100000 01111010 01100101 01110010 01101111 01110011 00100000 01110100 01101000 01110010 01101111 01110101 01100111 01101000 00100000 01110100 01101000 01100101 00100000 01110011 01110111 01101001 01110010 01101100 01101001 01101110 01100111 00100000 01100011 01101000 01100001 01101111 01110011 00100000 01101111 01100110 00100000 01100010 01101100 01101001 01101110 01101011 01101001 01101110 01100111 00100000 01101110 01100101 01101111 01101110 00100000 01110001 01110101 01100101 01110011 01110100 01101001 01101111 01101110 00100000 01101101 01100001 01110010 01101011 01110011

And now I have written it down.

I’ve turned my thoughts and feelings into an obscure thread of ones and zeros I am about to cast out into cyberspace. But where this thread is leading me—-I have no idea. My mind can’t tell me anything, it is still just a swirling mass of blinking neon question marks. The swirl is slowing now because my brain is tired and I must sleep.

Alex, Alex . . .

I can see you standing near the edge of an abyss . . .

Why won’t you let me help you?

_______________________________________

-

Some background on Parallel Journeys

The intention to write something like Parallel Journeys dates back to the summer of 1978 right after I first discovered and wrote about the Singularity Archetype in a philosophy honors paper, Archetypes of a New Evolution. After completing the paper, I had the strong intuitive realization that the best way for me to explore the Singularity Archetype, and to present it to the world, would be to write a fantasy epic. I planned to continue my research and nonfiction writing on the subject, and that culminated a couple of years ago in the publication of my book, Crossing the Event Horizon—The Singularity Archetype and Human Metamorphosis. I felt then, and feel now, that the fantasy fiction version would be more potent, however. To some, fantasy fiction is a form of trivial escapism. In Pushing the Envelope–Boundary Expansion into Novelty in Personal and Evolutionary Contexts I make the case that fantasy fiction, which Tolkien called “subcreation,” is at the cutting edge of evolution. I know that sounds like an over-the-top claim, but you can read my case (or listen as podcast) to see if this is a rational conclusion.

The earliest versions of Parallel Journeys that bear any resemblance to its present form began in the early 80s. I regarded all my attempts as experimental and kept reworking the material. I also found that different than almost anything else I was drawn to by the creative muse, Parallel Journeys was both the most desirable project, and also the least available, as it depended on visionary access to other planes of reality. I’ve written about some of the ups and downs of my struggle with this project in my essay (and podcast) on creativity, The Path of the Numinous—Living and Working with the Creative Muse. Most of you are probably familiar with Malcolm Gladwell’s concept of 10,000 hours of practice as necessary to achieve world-class proficiency at anything. While I’m way over that standard in nonfiction writing, I have a long way to go before I log 10k hours in fiction writing. So even though much of the nonfiction practice carries over, and even though I got a master’s degree from the NYU creative writing program in the 80s, I still have a lot to learn about writing fiction at the level at which I want to write it.

One of the first versions of Parallel Journeys was a novella entitled Spiral that was my master’s thesis at NYU in the mid-eighties. It was signed by my beloved writing mentor/teacher/adviser one of America’s greatest novelists, the recently late, great, E.L. Doctorow <<link to a brief obit I wrote for Reality Sandwich.

Compounding this is that Parallel Journeys involves experimental narrative devices and surreality on a number of levels and that requires much more skill to pull off than conventional fiction. I have high confidence in the creative process and have scarcely missed a predawn Parallel Journeys writing session since the autumn equinox of 2013. A few days before the autumn equinox of 2014 I finished the rough draft and since then have been working with my editor, Austin Iredale. The revision process could take a few years. As of December 2015, I am about 14 months into the revision and have yet to finish work on chapter 3. During April 15, 16 and 17 of 2015 I had a whole series of realizations of how I could make nearly every part of the book better and that has made the revision even more extensive and protracted.

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

I’ve been assured that 75 have come through (really) as of the date of this posting. powerful beacon.