Beauty in the Eye of the Phase Shifter

© 2006, 2008 Jonathan Zap

Edited by Austin Iredale

(On May 31 of 1996, a morning of intense intuitions drastically changed my view of corporeality, beauty, sexuality, and eros. This experience is described in “The Path of the Numinous” and the intuitions of that morning are developed in “The Glorified Body—Metamorphosis of the Body and the Crisis Phase of Human Evolution,” and that work serves as a foundation for the present reflections. In writing the following reflection, I use the pronoun “we,” by which I mean “me,” but also the many others who have parallel feelings. There are some for whom the experience of beauty may be quite different, especially those who have been conditioned by pornography, those who view sex as reducible to concrete actions on the genital level, and those most attracted to the human form when it is earthy, explicitly sensual, and unetherealized.)

When we look at a person that has numinous physical beauty, there are so many layers of projection; archetypes like the anima and the eternal youth may be evoked. But what we also project is the intense inner urge to be phase-shifted to a plane of existence where matter is more animistic, more imbued with spirit, more interactive with psyche, and transformable by will and psychic intention.

The suffering and anxiety associated with the present plane of existence are almost too obvious to be stated. Most of us are at war with time and corporeal limitations in many ways. The oppression of bodily circumstances that defies our will ranges from a bad hair day to a crippling disease. When we see numinous physical beauty we feel a soaring sensation; it is as if we are seeing the soul freed from its corporeal imperfections and metamorphosed into a perfect form. The soaring feeling of perfect grace and beauty may also be accompanied by a contrasting feeling of intense desire, which in itself may not feel soaring, but rather is marked by an enslaving appetite, a sense of incompletion, and an insatiable hunger for sexual transaction. If the beautiful other is related to us in a loving mutual romance, then there might be more soaring and less hollow enslavement. But if jealousy enters such a union, then the soaring too becomes a hellishly earthbound suffering.

Many people, at different times and places, have described what I have referred to as the “Green World” (see “A Splinter in your Mind.”) It is a world alike ours, but phase-shifted to a more animistic and idealized plane. We see some of that in Tolkien’s Middle Earth, especially in the elf realms of Rivendell and Lothlorien. Inhabiting these phase-shifted places are immortal elves who are more physically beautiful than mere mortals; their bodies are the uncorrupted manifestations of a divine image.

On our much more messy plane, when we encounter numinous physical beauty, it seems as though we’ve found a beautiful gem sparkling in the gutter, one that arouses our delight and sometimes our greed. It is as if a secret has been revealed that deeply concerns us, and we may feel the illusory projection that this beautiful person belongs to us in some way, is destined to be ours. (If this feeling is taken literally, we might become a stalker, etc.) The beautiful person glows, shimmers, and lights up in our mind’s eye like an angel, a being that is human but phase-shifted from corporeal limitation.

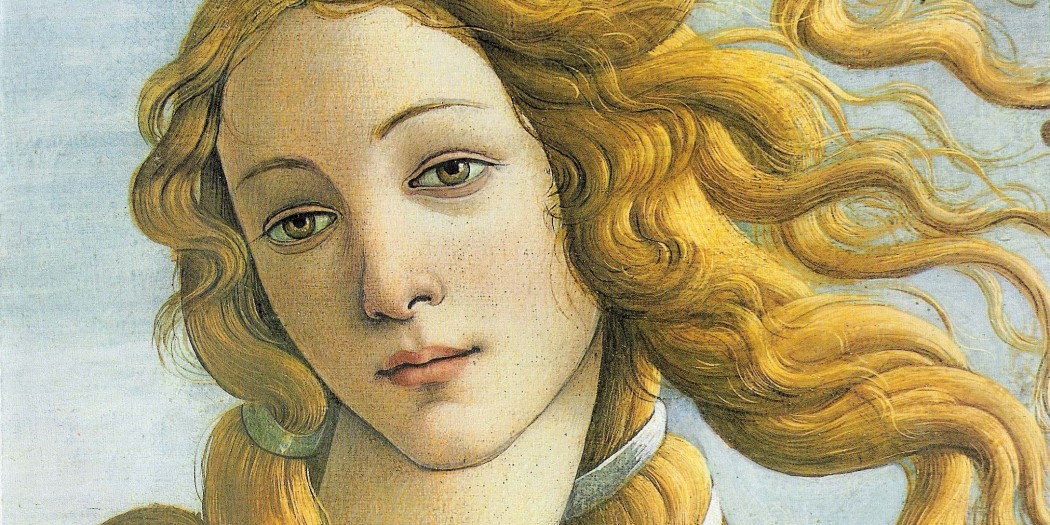

What exposes this projection is a realization that the actual human, temporarily gifted with such a form, is still chained to corporeality, to the likelihood of sickness, the inevitability of aging, to fatigue and indigestion and so forth. But at the first moment of perception, it is as if they were Botticelli’s Venus stepping out of the clamshell, as if they were light streaming the through stained-glass windows of a Gothic cathedral. If we could only merge with them we would be complete, we would be in heaven. In other words, we project and interpersonalize our urge to merge with the glorified body, our urge to phase-shift to a greener, more divine world than our own. We sense that there is a slider switch—and there absolutely is such a switch—that shifts the matrix from coarse and vulgar to more subtle and divine. If you doubt that there is such a switch, try the following thought experiment: You spend three or four days in a small cabin by yourself near a wildflower meadow in the Rocky Mountains. It is late June and the days are long and glorious, the nights clear and filled with stars. During your stay you fast on fresh fruit or fruit juices, and spend much of your time meditating. Next you spend three or four days in a seedy motel room in Newark, New Jersey, watching pay-per-view porno on the motel television, drinking Night Train Express and buying all your meals at the greasy spoon across the street from the motel. These two poles of experience give a rough idea of how much play there is with the slider switch on this plane. Circumstances, outer circumstances, bodily condition, emotional state, etc., move the slider switch. But we want to be able to move the slider switch even more; we want, sometimes, to be able to move it into a greener world, a world where we, and the human forms we behold, have the beauty of Tolkien’s elves.

Some imagine those with beautiful bodies to be phase-shifted and unbound from this world, and long to be amongst glamorous celebrities arriving at the Oscars with flashes strobing around them. If only they lost weight, had plastic surgery, and were a wealthy celebrity, then they would live in a world of light and beauty. It is easier to see through such delusions when they manifest in someone else, rather than when they are present in ourselves, just as it is so much easier to see when a close friend is getting involved in what is likely to be a disastrous romantic relationship, etc.

When we see a person of numinous physical beauty, it seems as if they are made of finer stuff, as if a light were shining through them. Some of this perception can be explained objectively. A young person with a perfect complexion and glossy hair is an objectively contrasting form to a person with wrinkled, blemished skin and dull, thinning hair. Although we constantly hear that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”—and there is some truth to that: different people are attracted to different types— it actually turns out that there is wide agreement across cultures as to who is good-looking and who is not. Studies show that photos of people are ranked almost identically based on looks, by people of all types and from the most varied of cultures. Objective qualities of beauty have even been codified mathematically, and it has been shown that those consistently ranked as more beautiful have superior facial symmetry and proportions that conform to the mathematical ratios of the golden mean. (Find out more about this research by watching the four part BBC documentary Face to Face)

Human beauty is not merely subjective and observer dependent; some bodies are objectively more perfect realizations of the human form than others. But even a person who has such a body, has it only on loan, because unless they die young—a wise career choice for those who want to be, like Marilyn Monroe, an enduring object of projection—they will outlive that perfection.

But when we encounter a beautiful person in such an idealized form, it seems as if they have found a magical secret, have drunk from the fountain of eternal youth, and in our psyche that person appears like a shimmering portal—if only we could enter such a portal we would be transformed and released from the suffering of corporeal incarnation. If we form an actual ongoing relationship with such a person, however, we become aware of the temporal fragility of their beauty, and the suffering of corporeality will now include the suffering of watching the beautiful beloved lose the perfection of their divine form. This state of poignant loss was expressed in a perfection of words a few hundred years ago in Shakespeare’s Sonnet XV. It was written, like all of his sonnets, when Shakespeare was in love with an androgynous male youth, probably the most temporally fragile form of human beauty.

Sonnet XV is an impossible act to follow, so I will close with it, but I would like to suggest that the reader, after reading XV, consider the many ways and layers in which we individually, and as a species, in our contemplation of our own bodies, and in the ways in which we behold the bodies of others, are “…all in war with Time…” and on a misconstrued personal quest to reach that phase-shift which shimmers beyond the portal of death, and also at the evolutionary event horizon of our species.

Sonnet XV

When I consider every thing that grows

Holds in perfection but a little moment,

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment;

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and cheque’d even by the self-same sky,

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory;

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight

Where wasteful Time debateth with Decay,

To change your day of youth to sullied night;

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

Thank you for taking your time and putting your self into this site. If I werent so imaginary, I’d have coin of the realm for you, alas. <3