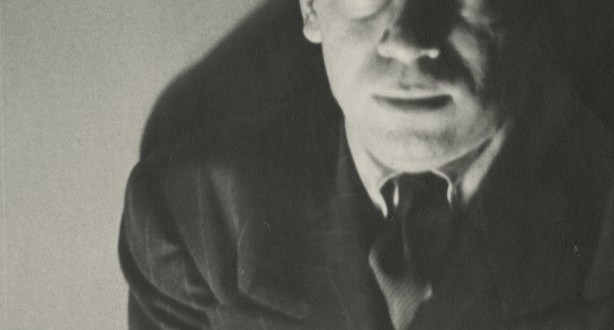

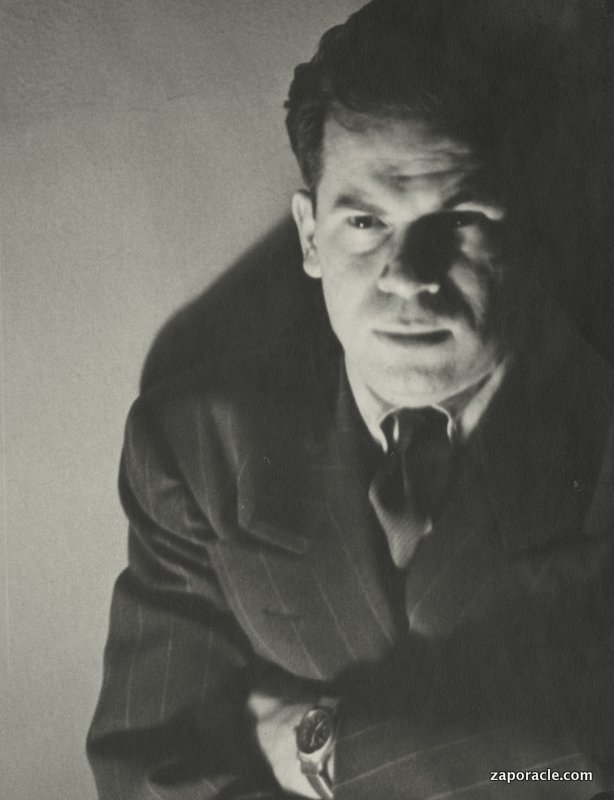

Nathan Zap (born 1919) in the 1950s, probably a self-portrait (he was an excellent photographer and painter).

text copyright Jonathan Zap 2012, photo copyright Nathan Zap 2012

From the point of view of body and ego, there is no safe walk through life, and no one gets out alive. How you respond to the unsafeness of life will determine much of your character and life experience. Handle it well and the dangers to body and ego will leave your soul intact and perhaps even enhanced by a challenging incarnation.

That’s the short version, but for those with the time and inclination to go deeper, there’s more:

There is no safe walk through life. This card arose from a visit to my parents who live in the Bronx. My dad, who is just shy of 93, has moderately advanced dementia. Often he can seem pretty disassociated, but he also has flashes of high lucidity. While I was there, my mom, in a paternalistic voice, told him, “Now, take a safe walk to the bathroom.” My dad replied, “I can’t take a safe walk through life.”

Sometimes people may sum up their central life theme in a single sentence. I’ll never forget the statement made to me by an inner city kid when I was the building security coordinator of a public high school in the South Bronx during the years of the crack epidemic. He was creating a disturbance in the hallway and I told him he had to leave. “I ain’t gotta do nothin’ but die.” he replied. His statement captured his essential life stance in the fewest words possible.

Similarly, my dad’s statement, “I can’t take a safe walk through life.” had an oracular quality. It captured his essential view of life, and coins a valid life principle. He lived through the Depression and often spoke about the “Hoovervilles” he saw growing up in the South Bronx (homeless people living in shanties). His family was fairly well off, but he witnessed how society and an economy could break down. Far more influential, however, was a double shock that occurred to him 1n 1943-44. In May of 1943, his mom, who seemed very healthy and full of life, died suddenly. On the plane ride back to NYC to attend the funeral, the army had someone sit next to my dad because they thought that he might jump out of the plane.

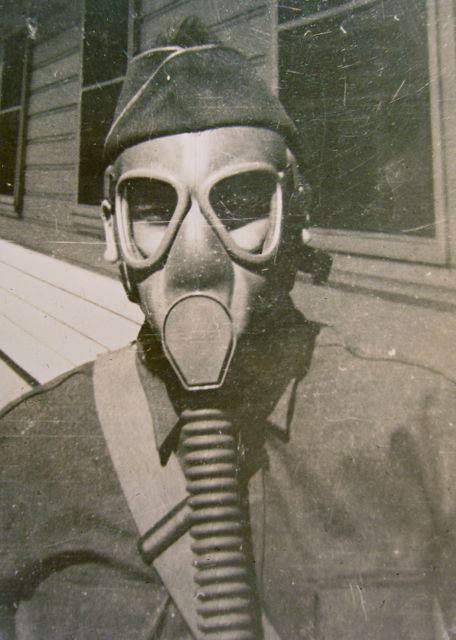

My dad spent most of the war working as a microbiologist in an underground lab specializing in parasites and incurable venereal diseases that servicemen were picking up overseas. They worked with live culture slides in those days and there was a lot of risk of accidentally becoming infected with the incurable diseases you were studying. This experience helped to give my dad a very dark view of nature, and he often warned me about the risk of disease that could be incurred by petting animals or being careless with sanitation, etc.

Right at the end of the war he was pulled out of the lab and into D Day. My dad was a medic and everyone he knew during the war died on D Day except himself. He almost never talked to anyone about what he experienced during the war and still suffers from PTSD symptoms. Whenever anything about D Day came on television during the 60th anniversary, for example, he would walk out of the room. Following a minor stroke a couple of years ago, he was given some neuropharmaceuticals that apparently had a disinhibiting effect. He unexpectedly told his neurologist something about D Day. He told her that he was stacking up German bodies like firewood when General Patton came along and told him to step out of the way so he could get a trophy picture of himself taken in front of the pile of bodies. My mom said that was the most she ever heard him speak about the war in sixty years of marriage.

The essential message I would so often get from my dad about life was that it was unsafe. When I would talk about various plans and endeavors he would typically respond with disaster scenarios of how things might go wrong for me.

Although he viewed life as dangerous, my dad didn’t retreat from it. He was a genuine tough guy with a fierce, intimidating physical presence. A few times I saw him back down dangerous persons just with his demeanor. In his seventies, he was walking a woman back from a neighborhood association meeting when they were approached by a kid with a handgun who wanted to mug them. My dad yelled at the kid in such a furious manner that he ran away. Fierce defiance was his attitude toward the unsafeness of life.

Of course, my dad was not wrong about the unsafeness of life. Headlines and if-it-bleeds-it-leads news media may exaggerate the unsafeness, but unsafety is always with us, usually just a few feet past the imaginary guardrail.

Once my dad found a prewar Zeiss binocular microscope at a thrift store and pulled out a collection of glass slides he made during the war. He had me peer through the microscope to look at spirochetes, the microbe responsible for the then incurable variant of syphilis he had been working on. Stained red, the spirochetes looked like mattress springs sharpened at both ends. It was like looking into the dark heart of nature.

An exceptionally brilliant and capable man into his late eighties, my dad was a charismatic conversationalist always able to make people laugh with his darkly cynical observations and anecdotes. Although he viewed life as dark and dangerous, he had strong ethics and a sense of social responsibility. He was the leader of a socialist faction in the forties and fifties, worked with inner city kids, and served many terms on the Bronx Community Board.

His stance toward the unsafety of life was one of obsession, intellectual and scientific investigation, fierce defiance, dark humor and social responsibility. The “I ain’t gotta do nothin’ but die” kid had a simpler and harder to redeem stance toward the danger of life.

If you look at my dad’s statement, “I can’t take a safe walk though life,” in context, you see a transcendent function capable of redeeming the darkness of life. An interesting finding from near-death experience research is that there are cases of people with very advanced brain damage (catatonic Alzheimer’s for example) who will have a few moments of perfect lucidity before they die. The findings of NDE research contradict neurological materialism and show that consciousness does not require a functioning brain. Near-death experiencers have all confronted the no-safety aspect of being embodied, but also usually discover that dying is much safer than they realized. Looking past the content of my dad’s statement, we see him able to transcend his neurological condition and, without missing a beat, reinterpret my mom’s statement in a soulful, ironic way that makes a sweeping philosophical assessment of life in a single sentence.

Usually, my dad is in a helpless, dependent relationship to my mom these days, but in a few cases he’s also been able to transcend his neurological condition when she was in trouble. For example, one night my mom, who takes blood-thinning medications, woke up in the middle of the night to find that she and the bed were soaked in blood from an out-of-control nosebleed. When my dad is awakened in the middle of the night he is often completely disoriented and unsure of where he is, sometimes who he is, and of any division between dreaming and waking. On this occasion, however, the army medic side of my dad reemerged and he was able to take command of the medical emergency.

Life gives us blaring headline evidence of its unsafe aspects, but if we look carefully we also see evidence that values and essence can survive the many dangers of life. While some deal with the unsafety of life through denial, self-medication, and violence toward others, there are also life-affirming ways to take an unsafe walk through life. Consider the occurrence of this card a propitious time to examine your stance toward the unsafety of life.

Although life is dangerous, death appears to be perfectly safe. See:

Life Lessons from the Living Dead and the chapter on NDEs in my book Crossing the Event Horizon — Human Metamorphosis and the Singularity Archetype.

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle