WATCH THIS CARD AS A VIDEO

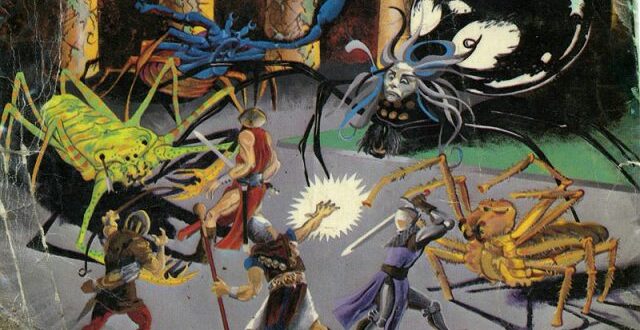

The Devouring Mother is the archetype of the devouring aspect of nature/the feminine. An addict* is an example of someone caught in the jaws of this all too real archetypal force. Parasites, which outnumber all other species four or five to one, embody this energy. People (individually or in collectives such as governments) can be parasites or predators and embody devouring mother energy. The battle with this archetype could be within, without, or both.

The Gorgon of Greek Mythology is an example of the archetype of the devouring mother. But this archetype is not merely found in ancient mythologies; you can find many personifications of it walking down a city street. It could be a coworker who wants to see you fail, an addiction that would like to consume your money and health, or a sexual vampire. In some cases, literal mothers may embody this archetype. For example, mothers who infantilize and over-protect their children to keep them helplessly dependent personify this archetype. As someone pointed out, there’s a difference of only one letter between “mother” and “smother.”

I use the excellent AI editing tool, Grammarly Pro, but when I used the common and concise noun “addict,” a smothering and infantilizing AI helicopter mother emerged trying to castrate my use of a blunt but accurate noun:

In 2024, when I revised this card, I searched online for this archetype and found almost nothing, not even a Wikipedia article. Both toxic masculinity and toxic feminity are real, but currently, one is emphasized far more than the other. The few online comments I could find about the Devouring Mother assumed it was only about literal human mothers rather than an archetypal force of nature that has so many other expressions. I’ve also found that when I talk about the archetypal feminine and masculine, even when I carefully explain that this does not equate to men and women and that we all have and need our unique combination of these elements, people will still accuse me of stereotyping men and women.

The Devouring Mother is a ubiquitous principle of nature, most dramatically embodied by the mating of the praying mantis, where the female devours the head of the male during copulation. Cancer can be viewed as a manifestation of the devouring mother. In human psychology, if a man or a woman lacks the archetypally masculine element of will to overcome an addiction or other self-destructive process that is consuming them, that is a manifestation of the Devouring Mother Archetype. As above, so below. You can find the Devouring Mother in human psychology as well as in the microbiological world.

Consider this an auspicious time to summon your will to defend yourself from the many forms of the devouring mother.

My two major works in published book form (both available free on this site) are relevant to the Devouring Mother Archetype.

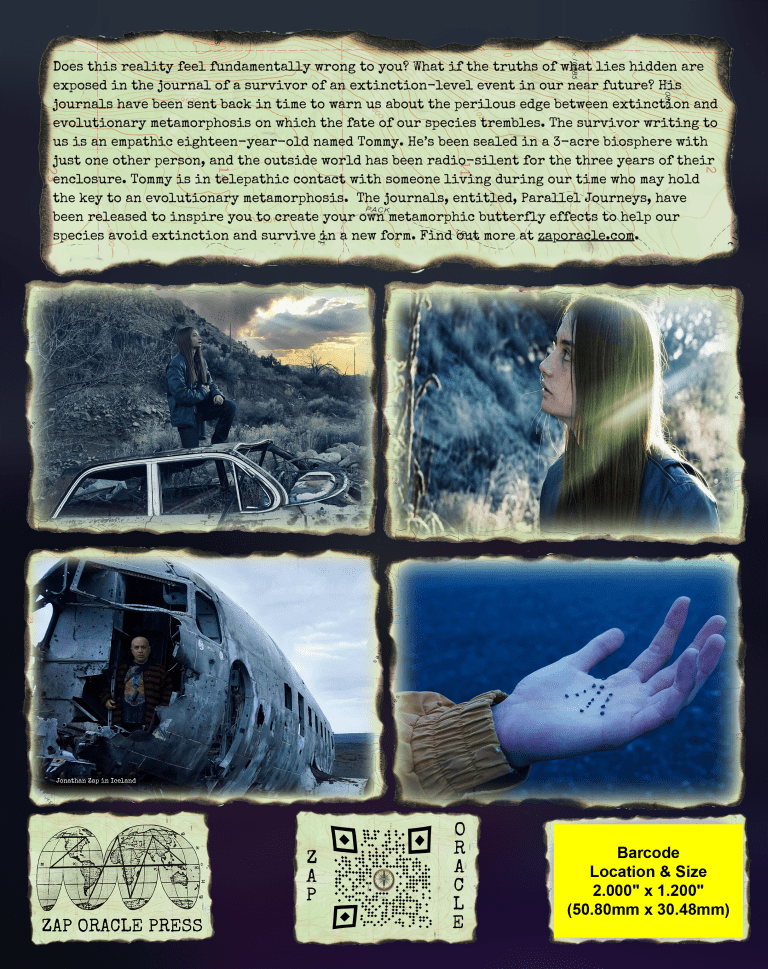

My sci-fi epic on the singularity, Parallel Journeys , includes an ultimate embodiment of this archetype.

.

Parallel Journeys, can be read free on this site. If you prefer Audible, Kindle or physical versions, those are all available on Amazon.

My book on the Singularity Archetype, Crossing the Event Horizon — Human Metamorphosis and the Singularity Archetype now has a second edition available free on this site. In the first chapter I attempt to concisely describe what archetypes are:

The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious

Jung and his colleagues have provided us with definitive evidence of a collective unconscious. From this collective layer of the unconscious emerge the great, primordial images Jung referred to as the “archetypes.” Archetypes are “innate universal psychic dispositions that form the substrate from which the basic themes of human life emerge.”5 Across cultures and periods, we find endless variations of these archetypes, such as the Self, Persona, Shadow, Hero, Great Mother, Trickster, Devil, etc. The archetypes may manifest in anyone but often show up most vividly in the fertile psyches of artists, poets, mystics, writers, shamans, and prophets. Through such individuals, the archetypes become myths and diffuse throughout a culture.

5 Papadopoulos, Renos, ed. “The Archetypes”. The Handbook of Jungian Psychology. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Edward Edinger, a Jungian analyst who wrote eloquently about the nature of archetypes, points out that although we can study archetypes as patterns, they are also living, dynamic agencies. Similarly, we could take a smear of human blood, dry it out on a glass slide, stain it, and illuminate it on a powerful binocular microscope stage where we could observe the structure of the erythrocytes and leukocytes. But while we’re looking at all the intriguing structures frozen in time on the glass slide, we need to also have a stereoscopic vision in which we see not only the slide but the inner reality of our bodies where blood exists as trillions of living cells pulsing through our veins and arteries. Archetypes are not merely things we observe. They are living agencies as active, pulsing, and alive within our psyches as the blood that is, pulsing and alive, coursing within our bodies. Edinger reminds us that the archetype,

“is a living organism, a psychic organism that inhabits the collective psyche. And the fact that an archetype is both a pattern and an agency means that any encounter with an archetype will have these two aspects.

“As a pattern, we can encounter an archetypal reality and speak about it as an object — an object of our knowledge and understanding. But as a dynamic living agency it appears to us as subject, as an entity like ourselves with intentionality and some semblance of consciousness.”

Jung, in his book, Answer to Job, describes the archetype as follows:

“They are spontaneous phenomena which are not subject to our will, and we are therefore justified in ascribing to them a certain autonomy. They are regarded not only as objects but as subjects with laws of their own. […] If that is considered, we are compelled to treat them as subjects; in other words, we have to admit that they possess spontaneity and purposiveness, or a kind of consciousness and free will.”

Jung rejected the idea that the human psyche was born as a blank slate, a smooth topography waiting to be carved by the forces of outer conditioning. Instead, he envisioned the emerging psyche as a landscape riddled with dry riverbeds shaped by the dynamism of the collective psyche operating across the millennia. When new vitality appeared, it would most likely flow into these established channels. This is why people from the most diverse cultures would all envision Heroes, Tricksters, Great Mothers, and so forth. Archetypes are the essential, primordial images stored in the hologram of the collective psyche. Each individual refracts these primordial images a bit differently, but the essence is still quite apparent.

Jung points out: “The hypothesis of a collective unconscious belongs to the class of ideas that people at first find strange but soon come to possess and use as familiar conceptions.”

Jung was an empiricist, and he used empirical evidence to demonstrate the existence of the collective unconscious:

“The hypothesis of the collective unconscious is […] no more daring than to assume there are instincts. One admits readily that human activity is influenced to a high degree by instincts, quite apart from the rational motivations of the conscious mind. So if the assertion is made that our imagination, perception, and thinking are likewise influenced by inborn and universally present formal elements, it seems to me that a normally functioning intelligence can discover in this idea just as much or just as little mysticism as in the theory of instincts. Although this reproach of mysticism has frequently been leveled at my concept, I must emphasize yet again that the concept of the collective unconscious is neither a speculative nor a philosophical but an empirical matter. The question is simply this: are there or are there not unconscious, universal forms of this kind? If they exist, then there is a region of the psyche one can call the collective unconscious.”6

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle