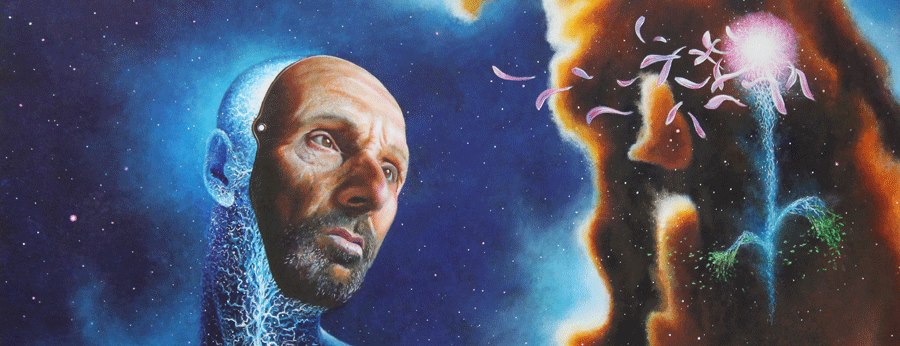

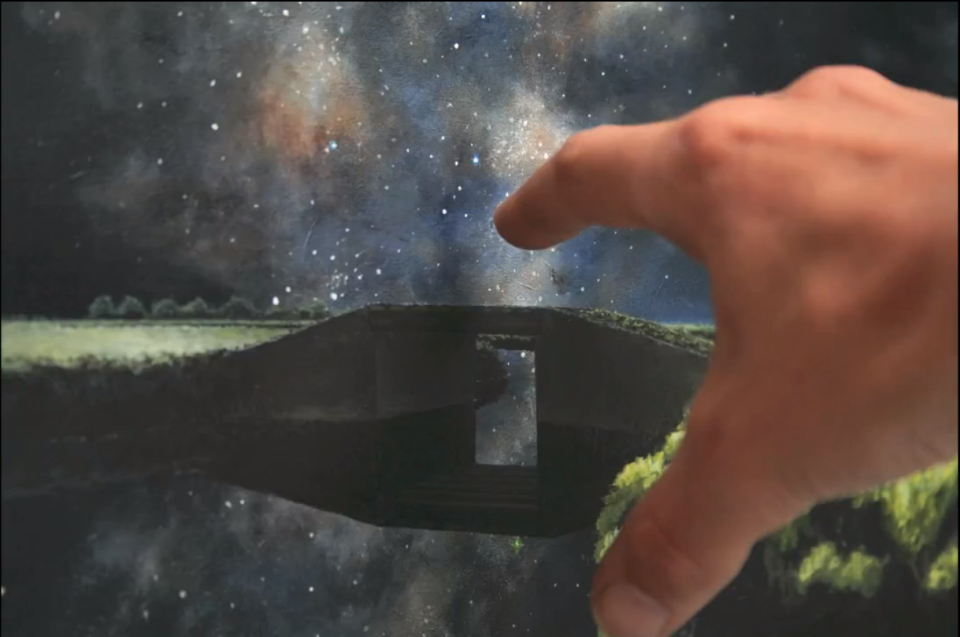

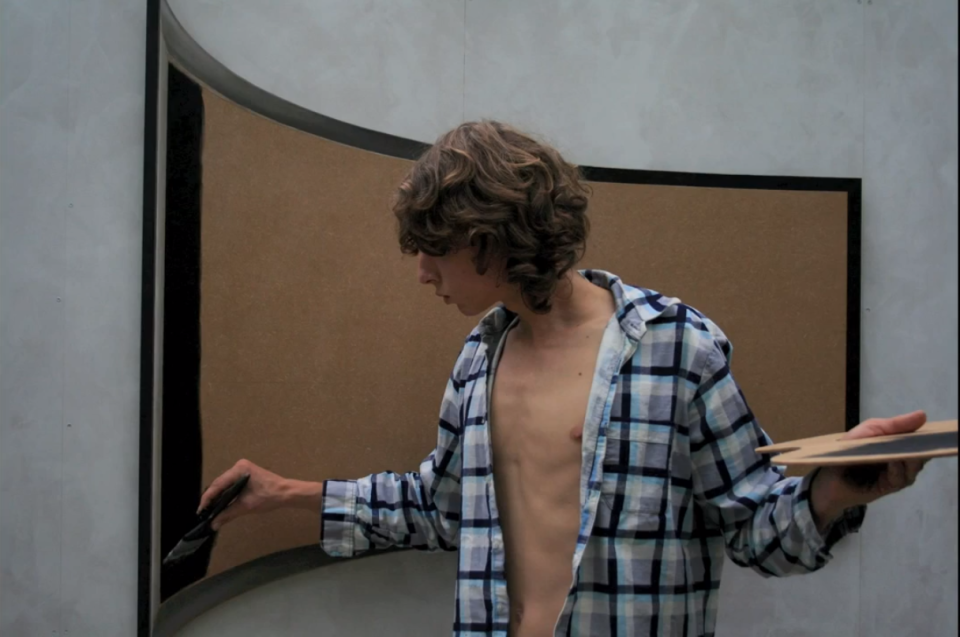

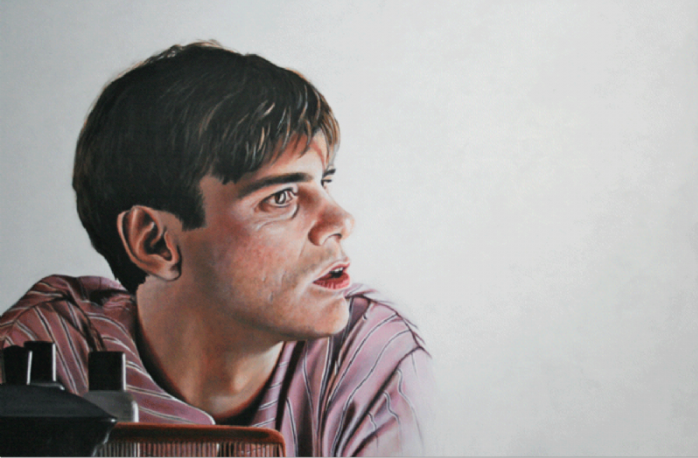

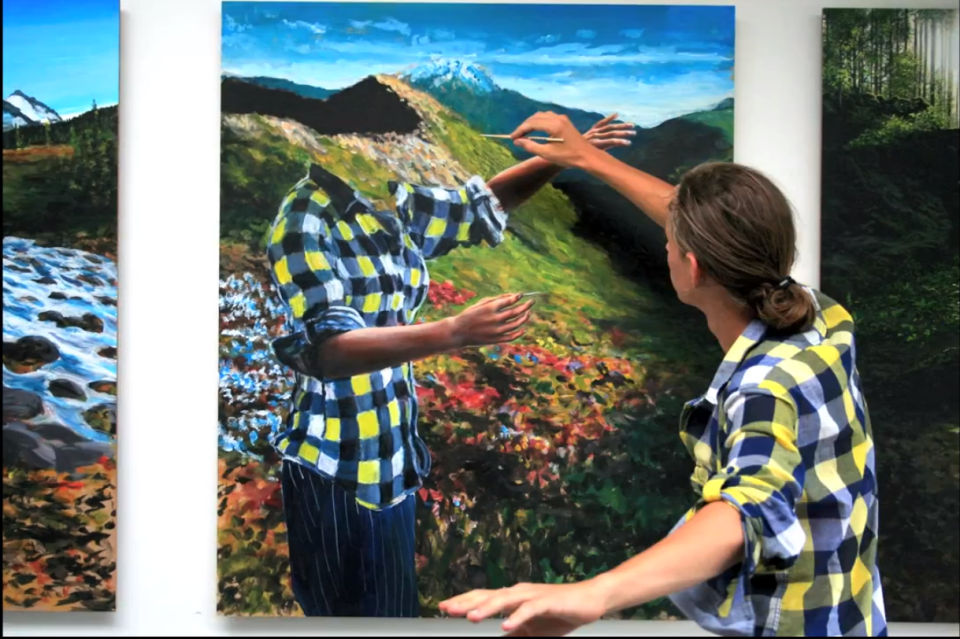

This photo (and all others like it) are still frames from I Paint

Top Image (old woman) is painting 12 from the I Paint Collection

Text copyright Thijme Termaat and Jonathan Zap, 2013. All images copyright Thijme Termaat.

Thijme is a self-taught artist who lives in a very small, rural town in Northern Holland. His amazing three-minute video, I Paint (click to watch it on Youtube), was constructed using simple, stop-motion and time-lapse techniques and no digital effects. It could have been made, as Thijme points out, a century ago. It would sometimes take him several days to construct a single frame and his output averaged one minute per year. Once it was complete, he posted it on Youtube and within three days it was being seen in almost every country on earth and soon had over a million views.

Thijme (responding to my request for an interview):

My work is free for interpretation, so I’m curious what you’d like to write about… What I mean to say by that is that I will not tell about my personal interpretations of any particular work, so I hope you had something else in mind.

Jonathan: I agree completely. I would never ask an artist of any kind what they meant by their work. If you wanted to express yourself in words you would be writing text and not painting. Any sort of artwork should be allowed, with whatever degree of ambiguity, to affect the perceiver of it without editorial comments by the creator. Some artists, writers and musicians foolishly (from my POV) respond to such inquiries, or volunteer them, and I almost always feel that it diminishes my perception of their work. For example, I recently found the song Monkey Gone to Heaven by the Pixies to resonate with my imagination. Of course, when anything interests me these days I will inevitably Google it. Unfortunately in this case, I got an explanation of the song’s meaning by its creator, and even though the intended meaning was profound, I was also profoundly disappointed. When an artist explains their work, it seems to collapse the wave function of a shimmering multitude of meanings into a single explanation and what had once been an iridescent and opalescent portal shrivels into a flat and opaque object.

My questions have more to do with the creative process and what motivates you to make the images. Let’s start with this question: Many of your images seem to involve actual subjects—people/places seen in the 3D waking world. Many of your paintings involve surrealized elements that appear in your interpretations of those actual subjects. Do you feel that these surreal elements are revealing things about the subject that cannot be seen by ordinary representational vision, or do you feel that you have created an alternate reality that borrows elements from the original subjects and then adapts them to create a new reality?

Thijme: Indeed my work contains a lot of surrealized every-day elements or objects. Mostly these surreal parts function as a crossover from one to the other layer, section or focus point of the painting in order to smoothen the line of sight for the viewer and also to mimic our dreamlike thought process. You cannot hold a picture still in your mind without re-taking your point of perspective every millisecond due to the holographic, feedback loop-nature of our thoughts and imagination. We all experience a constant stream of thoughts. Every thought we have smoothly flows over into another. I’m trying to embed that fundamental characteristic into my work in order to address the imaginational flow of the viewers, so that the experience becomes more of a “ride in their own minds.”

Merrily, Merrily, Merrily, Merrily… , 2013, acrylics on panel, 40×50 cm

Careful What You Fish For, 2013, Acrylics on Panel, 40X50cm

Jonathan: Thank you, that crystalizes for me what I experience looking at many of your paintings, especially the two very recent works (see above). You seem to brilliantly capture that sense of vision as a seamless, shimmering superimposition of ocular and imaginative layers in a way that allows the viewer’s eye to spiral into a portal rather than be stopped by any definite horizon line. I feel like this quality of your images allows infinite room for the imagination of the viewer to create their own inner experience of the image. You both capture the evanescent nature of your perception (as you describe above) and also invite and evoke it in the viewer—and that is an exceptional accomplishment!

I’m also interested in the origins of your art. Do you have visions? For example, the visionary painter Alex Grey reports encompassing visions that he has, sometimes in alternate states of mind, sometimes ones that seem to break through ordinary consciousness. Visions can also sometimes be enhanced, amplified, and more dimensional versions of scenes or subjects before one’s gaze, but other visions may be completely independent of ocular vision and seem to come from another dimension. Do you have visions of either sort, and how does that affect the painting process? What is the force that keeps you painting and got you started with it?

Thijme: Every thought seems like a vision to me. I experience a mixture of pretty intense and clear images, emotions, sounds of all kinds, patterns etc. while I think, and it’s unceasing. For example, at a certain point I decided I shouldn’t drive a car just because there is too much of a risk that I might wander off in my mind. But after very long observation it became clear to me that this flow of inner experience is a combination of what I like to call psycho-mechanisms. It’s the dance between these mechanisms that manifests these vibrant thoughts. At the same time these thoughts blur with the five-sense experience making it a pretty trippy reality to start with, once you become conscious of this process. And since all of this experienced reality is an imaginative rendering of impulses received by the body computer, it begs the question: What of this weirdness is actually true? or better: Is there anything to be called true at all? So through the observation of my thoughts and inner process the quest for ‘truth’ was set.

I Paint no3, 2011, acrylics on panel, 120x100cm

Jonathan: Many of your images seem to have a self-aware connection to magic and manifestation. You have also put yourself in some of the images, and at least one self-portrait has you in the pose of a magician conjuring. Aleister Crowley’s one-sentence definition of magic is, “The art and science of creating change in conformity to will.” All art, from that perspective, would be a form of magic, but in your art, magic also seems to be a self-aware subject. What connections do you see between your art and magic and between yourself as artist and as magician?

Thijme: I’m fascinated by the magic of manifestation. And by manifestation, I mean the manifestation of supposed reality. Magic, for me, is not so much a practice that can be done, but more of a word to describe how we interpret something we do not fully understand, which is the miracle of manifestation that is happening every perceivable moment with endless variability. I could wonder about the miracle of manifestation for the rest of my life without getting bored.

Since we experience reality solely from our ‘personal’ point of view, we have to be honest enough to ourselves to admit that there is only one single reality we can be sure of in existence for at least as long as we are alive. This is what I find so magical— that we all share this single manifestation and at the same time we shape it, like gods, to a strictly personal experience without any effort. This realization recognizes you as the editor of your own life experience. Yet I want to make clear that this has nothing to do with truth, since every concept or belief we use trying to explain this reality is merely adding up to an illusive story about it. This is why I use the word “editor” after “gods.” Like gods we shape it, but, like editors, we mold our experience of life into a juicy theory, using complicated terms and philosophies trying to explain how reality works. This is fine for the purpose of an exciting conversation with anyone who is interested in these ideas, but it is as far from truth as you can get.

Truth lies beyond explanation and therefor cannot be expressed, although every expression we come up with is truth expressing itself.

But if I cut this vast subject down to the case of manifesting a painting (for the sake of a clearer answer) I’d say: As an artist I try to make visible that reality is an illusion.

20% crop of a painting in progress

Jonathan: I have recently been exploring the work of Scottish artist/writer/chaos magician Grant Morrison. When Grant was creating his most famous work, The Invisibles, he wrote himself into his story and performed rituals to help open visions. The boundary between his art and his life blurred, and in Katmandu he had a series of life-changing visions that greatly influenced his personality, perception of reality, the Invisibles and other of his works. He writes about these experiences in his nonfiction book, Supergods, which is also about the history of superhero comics. Personally, I have had many dramatic blurred boundary experiences with my writings and especially my fantasy epic Parallel Journeys. So I’m wondering if you can tell us about any blurred boundary experiences you’ve had in creating your paintings and how you’ve seen magic influence your creative process?

Another way of asking this: You acknowledge the movie, The Truman Show, as an inspiration and have created a painting and made a video about it. The Truman Show is a brilliant representation of what we might call the “torn curtain” experience. Truman senses that the apparent reality is not complete, that it is a simulation generated by a larger reality, and he must go on a journey and have an epiphany wherein he steps through the curtain and discovers the reality behind it. What sort of torn curtain experiences have you had, and how does this relate to your art?

(Thijme chose to answer three of my related questions together. Here are the other two questions followed by his answer.)

Symbiosis, ” No Bumblebees without flowers, no beautifully colored flowers without Bumblebees…,” 2010, acrylics on panel, 5 x 7 inches

Collective Consciousness, 2010, acrylics on canvas, 35.5 x 23.5 inches

Lifesong, 2010, acrylics on canvas, 60 x 80cm

Jonathan: Many of your paintings (Symbiosis and Collective Consciousness are examples) beautifully illustrate divine principles manifesting in nature. In Lifesong, a raptor, probably a hawk, holds a small animal, possibly a mouse, in its talons, a small detail of predation and a rare moment, in your work, of acknowledging the dark side of nature. The predator seems only to add to the sense of the revelation of the divinity of nature. Is nature where you find you can best access the spiritual dimension? Georgia O’Keefe found she needed to live near the desert to find many of her visions. Do you feel this way about living in the Dutch countryside?

Between Heaven and Earth, 2009, acrylics on canvas, 39 x 53 inches

Death Shows us the Way, 2009, acrylics on canvas, 19.5 x 16 inches

Jonathan: Many of your images (Between Heaven and Earth and Death Shows us the Way are examples) have explicitly spiritual themes. What inspires your spirituality? Are you inspired by any religion, spiritual tradition or practice? Have you had your own spontaneous spiritual experiences? If so, could you tell us about any of those?

Thijme: I started to doubt my ‘programmed’ version of reality when I entered high school. I became very aware that the stuff we had to digest there would be useless to me in the future, and I knew for sure that the rest of my time there would be a waste. Nevertheless, I was a child, and adapted in such a way that my time there would be as easy as possible. Typical high school-survival mode, staring out the window and drawing instead of paying attention to the ‘lessons,’ but still I was unaware of the lie I was living in.

At 16, I started to get interested in sacred geometry, which gave me a boost of supposed insight and theories and a nice way to wonder about the nature of reality.

When I made the decision to quit the Design Academy six years ago, I certainly looked through a totally different set of eyes than I do now. The freedom I had created for myself finally gave me the time to work out this burning question: What is really true? I started to re-evaluate everything I had been taught before. Shitloads of shit and much more, nothing of it remained standing in the end, not even my self. Everything was illusion, and life but a dream.

This ‘realization of a dream’ never evoked a clear moment of epiphany with me. Perhaps this was because prior to my entering the phase of re-evaluating of my thoughts I had already gotten used to dealing with infinite structures in my mind, and everything that came after was more like solving a reverted puzzle that is finished when all the pieces are back in the box. By bringing it back piece-by-piece to its purest form and finally seeing it for what it always had been in the first place, we see a puzzle, and not the image it generates.

This search directly relates to my artwork of course. The contrast between life and death puts things in perspective when you search for what is true, so I have made a lot of works that depict this. Some paintings show this contrast very clearly, and others appear to be almost over-the-top, romantic landscapes with bright colors, but seem at a second look to contain elements of death. My fascination with the magical manifestation of thoughts and their surreal appearance due to the blurring of a multiplicity of operating mechanics within the psyche is also a common element, often worked out in the background of a depicted subject.

As much as I would like to think that moving closer to nature would bring me more inspiration, I like to remind myself of the immortal words of William Blake:

To see a world in a grain of sand.

And a heaven in a wild flower.

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand.

And eternity in an hour.

Inspiration comes from within.

Truman, 2011, acrylics on panel, 35.5 x 23.5 inches

Jonathan: In comments about your painting, Truman, you write:

“Truman talking to his mirror– a beautiful metaphor for the endless inner dialogue in which we try to explain everything in our world.”

What is the connection between inner dialogue and your artistic process? Do you do practices to change or suspend your inner dialogue to be able to see the world differently or to see alternate realities?

Thijme: This inner dialogue, with all its aspects, is inevitable because it’s always there. But it is the choice to investigate and eventually accept it for what it really is or not that makes the difference between one who falls victim to his inner dialogue or not. If the origin of your thoughts is not clear to you, you will not see through them, and will become a slave of your own corrupted psyche, eventually leading towards self-tyranny. This inner oppression can vary from mild to extreme cases because when you are not in control of your own mind you will tend to want to rule the mind of someone else to compensate for the lack of control of your own inner life.

I do practice a kind of meditation daily for just a minute or twenty, but that is not to change or suspend anything. There is nothing to be suspended because it is always there; at least that is my experience. I can only turn my attention towards it or away from it.

I’m used to my imagination running wild all the time and it has become part of my life. I can see the world as I will, when I will, just like anybody else. There’s no need for meditation or any other practice, because imagination is powerful enough by itself. And yet again, we have to realize that how we choose to see the world is only the picture we see on the puzzle; it doesn’t say anything about the puzzle itself.

Jonathan: What’s great is that you recognize the contents of your psyche as valuable, as something to accept and investigate. This is a great part of what makes you an artist. Many people view this sort of streaming inner content as toxic and problematic and Jung called the negative aspect of it psychic entropy. Psychologist Martin Seligman and others have researched psychic entropy and have found that most people, even those who say they prefer solitude, are happier in company because the presence of others diminishes psychic entropy. So most people are trying to turn away from streaming inner content through socializing, television, etc. Some people view meditation as a practice to help them shut down inner dialogue and content. What’s refreshing is that you seem to have chosen to turn towards the inner content, but not just as passive witness. What you do seems much closer to what Jung called active imagination. Apparently, you have been investigating, amplifying and utilizing that inner content and this comes across in your paintings as a celebration of imaginative possibilities. Many other painters have looked within and painted images of grotesque and pathological inner realities (the Freudian nightmarescapes of Salvador Dali, etc.)—which is fine—but we’ve had so much of that already.

Vague Predictions, 2011, acrylics on panel, 19.5 x 16 inches

Jonathan: The feeling I get from your painting, Vague Predictions, (the image and the title) is that ambiguity is a necessary part of many of your images and that you are comfortable with ambiguity in the creative process. What is your connection to ambiguity in your art?

Thijme: Ambiguity is a key element in my art. It forces the viewers to rethink what they saw, and choose for themselves what they want the meaning to be. This way, meaning is created from within the viewers themselves, creating an active relation with the artwork. By doing this, the viewers have consciously made it their unique interpretation of the work. This act of deciding what something means to YOU personally, within your version of life, is something that seems to be almost extinct in us, unfortunately, so I hope to give people a slight taste of what it feels like to find their own values in life.

Also, ambiguity enables me to communicate to people with the right eyes to see.

Forbidden Fruit, 2009, acrylics on panel, 4 x 7 inches

Jonathan: Describing your painting, Forbidden Fruit, you wrote: “An apple gives me more insight than a library full of books.” Do you prefer to draw inspiration directly from nature, rather than human culture, or written narratives in particular? Would you say that visual intuition forms your view of reality more than thought, intellect and the written word?

Thijme: What I meant by that is that we don’t need anything but simple observation and honest reasoning if we want to find out what is really true. Books account for all sorts of theories, beliefs and philosophies, which can be highly entertaining, but none of those are ever true. I know this may be difficult to accept for a lot of people, and I’m not trying to convince anyone by stating this. My intention is only to motivate people to see for themselves, and find out what is really true. Not because I think this is for whatever reason necessary, but simply because I like the challenge of finding a way to do so.

Just for the fun of it. No more, no less.

Realization of a Dream, 2007, acrylics on canvas, 39.5 x 55 inches

Jonathan: In your self-portrait, Realizing a Dream, you are depicted as breaking out of the frame of your own picture. Grant Morrison, in his series, The Filth, has superheroes that break out of the comic book panels and seem to be manipulating the reality of the comic book. In Kurt Vonnegut’s science fiction novel, Breakfast of Champions, the author puts on dark glasses and meets up with his main character, Kilgore Trout, an old science fiction writer, in a bar. A theme is emerging of the boundary between art and artist blurring, a theme I’ve seen play out in my life and work as well. How have you experienced this blurring of the boundary between artist and art?

Thijme: Yes, well my I Paint video is quite a blur already I think, but to me, separating art from artist is impossible. I shape my art and my art shapes me in return.

Jonathan: I’m glad you reminded me about your I Paint video which is how I, and many others, first became acquainted with your work. As of this morning it’s been viewed 1,266,876 times. Living in a small town in rural Holland, what was it like to suddenly get so much attention from so many people in so many places? Also, what inspired you to make it? How long did it take to put those three very inspired and inspiring minutes of video together?

Thijme: The inspiration to make the video directly relates back to my fascination for truth and its connection with the psyche. The whole movie is filled with illusion, imagination and manifestation. Time speeds up and slows down, paintings seem to be 3D all of a sudden and at the moment when you think you see through the illusion another layer of illusion unfolds. It is like a rollercoaster-ride through my mind. The video mimics this, blurring between psyche and 5-sense impressions.

It took me roughly three years to complete I Paint. I made it entirely alone, without any help and without a script. It is a combination of time-lapse and stop-motion, just still pictures with no digital effects. In fact, one could have made such a movie a hundred years ago. With the intention to make an inspiring video animating this blurred reality-experience, I just started working slowly towards the end of the film, frame-by-frame. Some frames took me whole days to create. If you look closely you can see my hair growing about six inches before I put it in a knot in the middle of the film.

Within three days after launching the movie online, it was already being watched in virtually every country in the world. It was just plain crazy. It was featured on hundreds of websites including MSN.com and Huffington Post, broadcast on Dutch, French and Japanese television, newspapers picked up the story and invitations and opportunities of all sorts were rolling in.

After this hurricane of attention had calmed down, I took the time to get my feet back on the ground and adapt to this new situation. Now, a year later, I can say that it was a successful project that gave me an enormous boost of motivation and reassurance that my work has a positive effect on people.

Jonathan: Wow, so one year of work for each minute of video, and no digital effects, that’s quite a concentration of meticulous craftsmanship! Your comments inspired me to go through it frame-by-frame which I found fascinating. Each individual frame is so well composed I would like to see all of them hanging in consecutive order in a giant gallery space.

I Paint gives people a chance to have an individual experience of looking through your eyes at the cascade of sense impressions, visualized thoughts and multi-layered images that are going on inside you. That’s why I think the streams of bubbles coming out of the frames are so appropriate—they are like thought bubbles, and bubbles are the most evanescent of structures with their ever-changing, iridescent, light conducting and diffracting watery membranes. Many people don’t have such a rich inner experience, or they don’t recognize the richness of it, they turn away from it toward the social matrix and a world of surfaces and superficial appearances. So this video is like your free access digitalized temple, a place where people can step in for three minutes and have an experience of what it would be like to turn toward all that rich inner content. Even more refreshing, the inside of your psyche isn’t the grotesque hellscape that we’re used to seeing from so many morbid contemporary artists like H.R. Geiger, etc. It’s as healthy and vibrant as Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

What was the original inspiration for I Paint and your starting conception? Did you realize you were embarking on such a massive project or did it start to grow as you got into it? Was their a unifying concept or theme you were working with or is that something you prefer the viewers to discern for themselves?

The Way of Paint, 2012, acrylics on panel, 15 x 18 inches

Thijme: Actually it was more or less my fascination about my own inspirational flow that inspired me to make I Paint. The intention was to make a clip that would show people how I experience a creative process. Physical and mental experience blurred together, just like in ‘real life’.

Multiple concepts, layers and ‘messages’ are embedded, but I like to leave those open to the interpretation of the viewers themselves.

I did not know beforehand how long it would take to shoot the film, but after a couple of months it became clear that it was going to take me at least two years.

Behind the Canvas, 2012, acrylics on panel, 20×24 inches

Jonathan: I Paint is timed and paced in such a way that the visual elements and the Vivaldi sound track become one. What can you tell us about the synergy of music and your art? How did you get the music and video to synch up so powerfully? Did you have Late Summer by Vivaldi in mind from the beginning?

Thijme: The music in I Paint was chosen from the start. I used Nigel Kennedy’s version, but I could not afford to pay the rights I needed to put it on Youtube worldwide so I had to make a remix of the song. This is the only part where I needed help in the creative process. The exact timing was needed to enlarge the flow-like feeling of the video. Every single note, I transformed into a stroke of my brush, a color appearing or whatever else I wanted it to be. This is the way I experience music when I paint. I wanted all elements to fall together seamlessly and create a more ‘whole’ experience.

unfinished painting from the I Paint Collection

Thijme: Music is a very important element in my creative process. I don’t have a musical background, and my parents weren’t really into music, so I had to discover most of it by myself. At 16, a friend of mine introduced me to the minimalist music of Philip Glass, in particular his Five Metamorphoses. After listening to it for several years, I wanted to play this music by myself and I started teaching myself piano. This opened up a whole new set of artistic possibilities for me, one of which was to record my own covers and use it for my video clips. Of course, I still like to listen to music while I paint. Some of my favorite composers are Hans Zimmer, Simeon ten Holt and Philip Glass. I use it to enhance my focus and to create a calm workflow.

Jonathan: You left design school after just two months to live and paint at home. What inspired that decision?

Thijme: After a couple of months in my first year at the Design Academy Eindhoven, I finally came to realize that school would not bring me any further towards the freedom I was longing for. At that point I made my very first painting with acrylics on canvas and it felt like I had never done anything else before. In the next few days I made two more paintings and in that short time I built up the courage to dream of a life as an autonomous visual artist. Upon that, I took the decision to move back home where I had plenty of space to paint. And so I started…

Jonathan: I think lots of people, including me, can relate to your decision to leave the academy in order to have more creative freedom. My rebellion from the confines of academia, and institutional life in general, took a lot longer—fourteen years into a career as a tenured English teacher. Such decisions usually take some courage because many sensible and well-meaning people don’t understand how demanding the creative muse can be. You might be interested in my essay on relating to the creative muse: The Path of the Numinous—Living and Working with the Creative Muse.

Jonathan: You left design school in just two months. How did you learn to paint so well?

Thijme: I’m self-taught. From an early age I have been drawing and it was just six years ago that I made my very first painting with acrylic paint on canvas. The whole process felt very natural.

I have never followed any courses or read tutorial-books, I just went on trying and experimenting. The progression I made since I started to paint, is clearly visible when you take a chronological trip through my works. And still my ‘style’ seems to be constantly changing.

Kiki, 2011, acrylics on panel, 16 x 19.5 inches

Painting for My Brother’s Birthday, 2011, acrylics on panel, 19.5 x 16 inches

Jonathan: While many people in their early twenties can’t wait to get away from their families and venture out on their own, you chose to leave design school and apparently live and work from the family home. Family members are also frequent subjects of your art. Do you draw inspiration from living with your family and what makes you choose to live this way at an age when so many want to be off on their own?

Mom, 2008, acrylics on cardboard, 8 x 16 inches

Brothers, (father and uncle), acrylics on panel, 19.5 x 16 inches

Uncle Max TM, 2012, acrylics on panel, 16×20 inches

Thijme: When I moved back home I had to build up my name as an artist from scratch. I simply had nowhere else to go. But even if I had, I would still have chosen to live with my family. If the family dynamic is peaceful and filled with love, isn’t that exactly where we all would like to be?

Just look at how severely the family structure has collapsed in the west the past few decades. This disappearance of the only structure that provides us warmth and safety while we grow up will turn out disastrous, and we can already see clearly how it affects our children.

Although I was already ‘grown up’ of course when I went back home, I still wanted to live with my family, for the simple reason that I love to be with them.

Jonathan: This is very interesting and a refreshing view of family. There has been some fascinating research and writing about your generation, sometimes called the millennial generation (roughly people with birthdates between 1982-2004). Strauss and Howe, who study generations, wrote a book about millennials: Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. According to their research, millennials are more positive and upbeat, and also more community and family oriented. Millennials, far more than other recent generations, will often say that they want to go to school or otherwise live with or near their families. So maybe you exemplify this generational change and reflect it in your artwork as well.

The Moment, 2010, acrylics on canvas, 23.5 x 31.5 inches

Some of the panels of a carousel painting project Thijme completed in 2012

Autumn on the Way, 2012, 18 x 18 inches

Jonathan: My friend Rob Brezsny has written a book entitled: Pronoia Is the Antidote for Paranoia: How the Whole World Is Conspiring to Shower You with Blessings. Rob is a frequent critic of the postmodern tendency to believe that only dark, transgressive art is sophisticated (and I’ve been a critic of this tendency too). Your art seems very pronoiac, and is a contrast to most of the dark, paranoid, dystopian culture that seems to be the reigning art form of the day. How do you come by your more positive view of reality and is this part of the general intention of your art (to reveal the hidden light and beauty of things)?

Thijme: Truth realization unites good and evil, fades separation and turns boundaries to dust. Dark is just the opposite pole of light, and they are both expressions of the same single manifestation. Hence, I see in essence no difference between the two, but I still have my preference of subjects and those are thought of by most people as ‘positive’ ones. It is our choice to focus on our likes and dislikes in life and I simply choose to focus on the things I like, without ever forgetting that they are only opposite poles of something that just is what it is.

I have no intention of showing what I think of as beautiful, but I just like to see people finding beauty and meaning within themselves.

Silent Adventure, 2012, acrylics on panel, 60×50 cm

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

I loved this–thank you.

Thank you for this. I’m going to link.

What an amazingly eloquent young man.

I just loved the interview and Thijme’s responses just as much as I love his work.

Unfortunately I am not in a position to buy any of his paintings but I really enjoy looking at the digital versions.

Thank you Thijme for being such an exceptional young man.

As a sidenote, I have never seen an ambidextrous painter before, AMAZING.

Cheers