I thought of Ali yesterday, before the news, when I read that Iceland (where I’m traveling) was about the size of Kentucky, which made me wonder about how Ali, who is from Kentucky, was doing these days. Then this morning, I awakened in Stykkishólmur, Iceland at 4am, two days before the end of four and a half months of travel to twenty countries, to the most intense vertigo I’ve ever experienced. It was like my head was mounted to a ceiling fan. Like anyone in the present era waking up under any circumstance, I reached for my five-inch life raft, the smartphone charging beside me, to find out the time and be reassured that I was still able to read and was not having a stroke. My fingers an inch from the phone, an email notification appeared, could barely read it, but decoded enough to realize that one of the most inspiring public figures of my life, Muhammad Ali, was down for the final count. My visual field was too blurred by the intense vertigo to read any details. Immediately after the shock of the breaking news alert, as if in reaction, a staccato cascade of texts began pouring in from a twenty-year-old I know, a martial artist with a warrior essence and all sorts of great talents, but who has also been experiencing life-threatening mental health episodes, telling me that he was about to leave his parent’s house at midnight to hitchhike across the country.

The moral imperative was to help him, to see if I could influence him, as I’d been advising him for a few weeks to stay put until his condition stabilized, but as I tried to sit up to compose messages, the spinning became so severe, all I got were gyrating, stroboscopic images of the ceiling. It was like my head was inside a rapidly spinning kinescope. It was nauseating, nearly panic-inducing, and yet I was struck by what seemed like a synchronicity—what I was experiencing must be close to what it would feel like trying to sit up after a knock out punch in a boxing ring. I flashed to something Ali said, something I read when I was a teenager, that boxing meant being able to stay on your feet when you were in a nightmarish, concusive zone where “alligators were playing trumpets.”

I knew I had gone to sleep with a fever and could feel I was badly dehydrated. There was a water bottle by my side, and downing half of it began to reduce the vertigo sufficiently for me to respond to the texts from my young friend six time zones away. He was about to put his pack on his back and head out the door at midnight, but he wanted someone to talk to first. Contradicting what he wanted to do never worked, but I advised him to stay put anyway, and, as usual, could see that paternalistic mode was only going to backfire. Giving up on resistance, I texted him that Ali had just died. His martial arts background gave him a bit more awareness of who Ali was than most millennials, but to someone born long after his retirement from the ring, Ali had always been a severely disabled living legend, not the larger than life figure he was to so many boomers like me who had grown up watching him float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.

He reacted with a text:

“Oh wow, no way. May his spirit live on! Perhaps I can conjure him for a little extra umph in my journeys.”

This kid was born fourteen years after Ali’s retirement, but he still sensed him as a source of inspiration.

Reaching for a straw, or perhaps a yarrow stalk, I asked my young friend if he would like an I Ching reading and he agreed. The I Ching app on my phone drew hexagram 5, Waiting, but he wasn’t willing to wait, he felt the urgency, the call to adventure of youthful risk taking and had already stepped out the door with his pack on, so I wished him luck and the next message I got from him thanked me for the reading and told me that he had already found a ride to the interstate.

The outcome of that impulsive choice is still unknown, but the saga of Muhammad Ali, the call to adventure he answered as a young man, the risks he took in the ring and out of it, the inspiration he brought to millions, if not billions, that hero cycle had just ended on this plane of reality.

Whatever time you wake up in Iceland this time of year, it’s light out, and with the impact of the news, and the light streaming in around the black-out curtains of my hotel room, three hours of sleep was going to have to be enough. The vertigo was slowly winding down as I pounded down more water and felt called to write something about Ali.

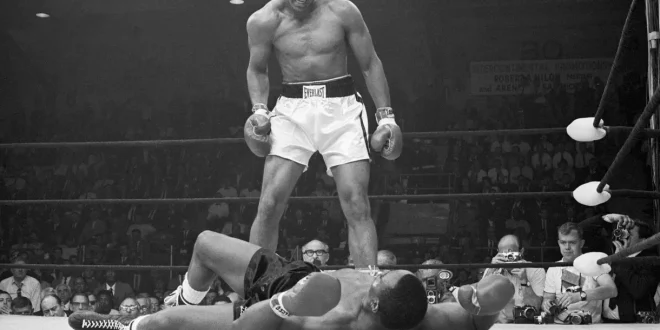

Even as a child I was fascinated by charisma, and by twelve I had concluded that the three most charismatic people I knew of were Muhammad Ali, Mick Jagger and Marlon Brando. All of them were artists, entertainers, but Ali could also make things happen in the brutally physical, blood-and-sweat-stained crucible of the boxing ring. Ali had more than stage presence, he had an uncanny ability to remain the last man standing when one after another of the biggest, baddest tough guys in the world had the opportunity and passionate motivation to beat his brains in. It was a form of credibility that no kid growing up, like me, in the Bronx, during some of the most violent years of that troubled borough, could fail to take seriously. Everyone wanted to be able to fight like Muhammad Ali— every kid my age wanted to stand over schoolyard bullies, like Ali stood over a stunned, horizontal Sonny Liston, and exclaim, “Take that mother fucker!”

Ali was the ultimate sports hero, even to a sports-hating kid like me who usually prayed that hometown teams would lose so I wouldn’t have to hear about it anymore. I lived a few subway stops from Yankee stadium and never went to a Yankee game. Actually, I went once as an adult, in the eighties, when I was teaching GED at the Bronx House of Detention, a horrible jail literally across the street from Yankee stadium in the South Bronx. As I was leaving the jail one evening, a desperate scalper sold me a ticket for $5. I walked into Yankee stadium for the first and only time, watched Dave Winfield hit a home run, got bored and left after about ten minutes. That’s how much of a sports fan I am, but growing up, whenever Ali flickered across our black-and-white television set, I couldn’t take my eyes off of him, even when I thought he was an arrogant and narcissistic asshole. And Ali certainly was a narcissistic and arrogant asshole at times, but more about that in a moment.

By far the most intense media event I ever witnessed was the “Fight of the Century,” the 1971 Ali/Frazier fight, a match between two undefeated world champions that happened in my hometown of New York City. The second most intense media event I witnessed in New York City was the clinical hysteria of teenage girls when the Beatles came to America to perform a concert in Shea Stadium in 1965. Even on the other side of town, in the Bronx, you could feel the crazed excitement of screaming fans. But Beatlemania paled beside the build up to the first Ali/Frazier fight that I witnessed (the build up, not the actual fight) at age 13. The news dominated all the New York media and the tension and excitement in the air had a crackling, third-rail voltage. I remember reading at the time that there were uncommonly few suicides that night in the United States because even the most desperate people had to know how the fight ended.

My mom, who had met Ali, was impressed with him, and since the family had been against the Vietnam war, Ali, who had famously resisted the draft and lost four of his best boxing years as a result, was perceived as having a significance not usually accorded to athletes in my anti-sports, intellectual family. But I remember being intensely irritated by Ali’s bragging and self-promotion. I had gotten zoned into a junior high school in the South Bronx, and during the month or so leading up to the Fight of the Century, a group of Nation of Islam kids in my junior high, who had Xs for middle names, specifically targeted me for daily harassment and beatings. And here was this braggart, Muhammad Ali spouting off about the Nation of Islam* and his mentor, Elijah Mohammed, and boasting about the beating he claimed he was going to deliver to Joe Frazier whom he repeatedly called a “gorilla” and “too dumb to be champion.” If a white boxer, or a white anybody had called a black athlete a gorilla their career would be over, but Ali had an ability, equaled only by Donald Trump, to deliver outrageous and undeserved insults and get away with it. Unlike the Donald, however, Ali had skin in the game, didn’t insult women, but saved his most vicious insults for other super tough black men who would get their chances to beat his pretty face in if they could. I wanted Joe Frazier to shut him up, but at the same time I couldn’t help but to be far more fascinated with dazzling, witty and ultra-charismatic Muhammad Ali.

*To his credit, Ali left the racist Nation of Islam in 1975.

The next day the New York Daily News ran a cartoon depicting Ali with his mouth zippered shut. But I remembered feeling this cognitive dissonance at the time— I felt Ali deserved to have his mouth zippered shut, but I was also disappointed because I was fascinated by his charisma and athletic and verbal brilliance. Ali had consciously crafted his trash-talking persona to be someone you loved to hate and the weird disappointment I felt forced me to realize the love that was mixed up in the hate he had also manipulated me to feel.

Like so many boomers, I came to identify with Ali’s arrogant confidence and trickster-like rebellion from social norms. But my early impression of Ali as a narcissist bully was not wrong. An HBO documentary, Thrilla in Manilla, reveals a very dark side of Ali who was both sadistic and racist in his treatment of Frazier who had helped him get his boxing license back and even given him money when he was struggling.

You don’t need to know much about boxing to watch the Ali/Frazier fights and perceive an archetypal difference between Frazier and Ali. Ali is the dazzling, far more talented and mercurial, almost magical athlete, while Frazier embodies a single, core warrior attribute: unbending intent. Frazier absorbs hideous punishment and never retreats, he keeps coming at Ali, even when both his eyes are swollen shut as they were in the final rounds of the Thrilla in Manilla.

But heroes are not supposed to be perfect. David took down Goliath, but he also sent an innocent man to his death just so he could get with Bathsheba. As Jung said, “The larger the man, the larger the shadow.” Jung probably hoped the quote would be applied to him since he was 6’6” and had a deserved reputation as a bully since he was a boy.

Ali, could beat up the best of them, but his uncanny gracefulness and speed had an androgynous aspect and he was always boasting about how pretty he was. He was a big, strong man but his hand speed was clocked as 25% faster than Sugar Ray Robinson, often considered the best pound-for-pound fighter in history, a welter and middle weight who weighed 50-60 pounds less than Ali. Ali’s famous rope-a-dope strategy he first tried on Frazier, but used with far more devastating effect on Foreman, was an androgynous strategy. (see my work on androgyny: Casting Precious into the Cracks of Doom—Androgyny, Alchemy, Evolution an the One Ring ). He allowed himself to be pummeled with body punches while he waited for his opponent to exhaust his fire. (see Zap Oracle card 630: Rope a Dope ) Using an almost feminine, trickster strategy, Ali was able to take down George Foreman, an opponent so powerful that sports pundits thought he might actually kill Ali. When Foreman punched the heavy bag while he trained in Manila, Norman Mailer said it looked like he might break it in half. At the end of the fight, I believe it was Howard Cosell in his memorable, nasal voice who said (approximately), “You can say a lot of things about Ali, but son of a gun, he delivers.”

In his most brilliant moments, Ali created the magnificent illusion that he could triumph not just over other boxers, but over the limitations of corporeality, limitations that the human species has an enormous will to transcend (see The Glorified Body). He brought such style and grace to the most brutal of sports that his best performances seemed superhuman. Baby boomers like me would fantasize about being able to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee while doing the Ali shuffle.

But even Muhammed Ali only got to be Muhammed Ali in that sense for less than twenty years. And then Ali became, like Christopher Reeves, a fallen superman, and we had to witness the terrible late career fights followed by the even sadder consequence of his attempts to fly too close to the sun— the melting of wings, the slowed, earthbound body, the loss of quickness with fist and word.

Ali is a genuine hero of his age— he personified the indomitable aspiration, the arrogant confidence and narcissism to take on social conventions and deliver amazing victories, but also the price that comes due when we attempt to heroically transcend the body while still being embodied.

Ali has heard the final bell and stepped across the event horizon that awaits us all. Perhaps in some other dimension he can once again float like a butterfly.

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle