Copyright Jonathan Zap 2026

Note to readers: this is a pre-publication beta test version. It’s been through a dozen levels of editing, so it’s pretty final but still open to feedback–which would be very appreciated–until publication, which will prob be in late April of 2026. Send any comments from general reactions to line edits to typos to [email protected]. Put Parallel Portal in the subject heading. I will be grateful for any feedback of any kind. If you prefer a Word or PDF version email me. Thanks, Jonathan

One

Tommy’s Journal

I know this will sound crazy, probably all of this will, but from as far back as I can remember, I’ve sensed an older version of me. I feel his presence, almost like he’s whispering in my mind, but I can’t quite hear what he’s saying. It’s like he’s helping me write this, like my words are coming from both of us. He’s looking out from the shadows of my mind, watching over me, worried about my well-being, and wanting to protect me from something dark that’s coming.

I’ve been having nightmares about it, the same nightmare again and again. In the dream, I’m waking up in my treehouse to the sound of gunfire, horrified as I realize that people in my community are being killed. The next moment, I’m standing beneath the treehouse. The gunfire has stopped, and everyone in my community, everyone I love, is dead.

The killer is out there in the woods coming toward me. He knows exactly where I am. I’m about to run, when I see a dark grey robot with a gun step out into the clearing where I’m pointed. It’s shaped like a person, but its head is a black machine with camera lenses for eyes.

Somehow, I sense that the robot is not the killer. Its lenses focus down on me, and then a voice, oddly human, from somewhere inside this machine, speaks my name, “Tommy,” and I wake up in a panic.

Even though I’ve had this nightmare many times, it still takes me a while once I wake from it to realize that my community is still here. That no one has been killed. That I am still okay.

But am I?

The nightmare doesn’t make any sense. My home and community are peaceful, remote, tucked deep in the Green Mountains of Vermont. Why would anyone want to kill us? And I’ve seen pictures of military and police robots—they’re not shaped like people, and their weapons are built in. But what is it trying to tell me? I sense something dark is coming, but I have no idea what it is.

I feel like that older version of me holds the answer. I’ve had visions of him since I was a child, writing in a journal, words being typed out on a computer screen. Something always kept me from reading what he wrote, but I knew it was a journal. In the visions, he looked about the age I am now, but he seemed older, like he’d lived through much more than me. I think he’s lived through what’s coming, but it’s like he’s not supposed to interfere. It would be wrong in some way. I’ve got to guide myself through the darkness, and that’s why I need to write this journal. I need a place to try to figure things out.

I also have a strong intuition that I’m needed to write this journal. Like there’s someone else who will need to read this one day. I can’t see who that person is either, but I feel them wanting me to continue.

I have no idea who you might be—the person reading this—but I sense you out there and I feel like I owe you this record. I don’t know why you’re the one who needs to read this, especially since I’ve kept my strange experiences secret from everyone I love—the people I live and work with in my small community called The Friends.

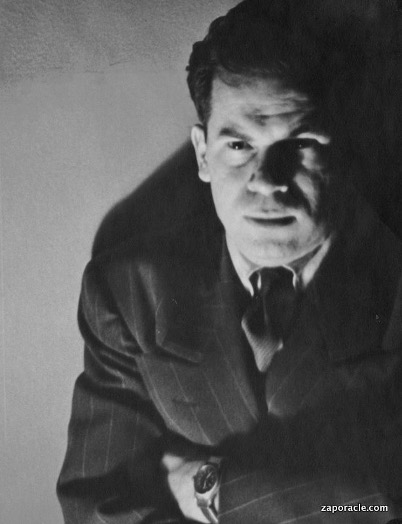

Now, I feel like there’s more than one person watching me. A strange image just flashed into my mind. I saw an older man in a dark room. Behind him were what looked like sophisticated but antique electronic devices with dials, knobs, meters, and red and green lights. It feels like he’s monitoring everything I’m writing and even my thoughts. I think he’s one of the people meant to read my journal, and I sense good intentions from him. The image disappeared pretty fast, but I feel like he’s still out there, watching me as I journal alone in my treehouse, swaying in the howling wind.

I always come here to write or when I need to be alone. And lately I’ve needed that a lot. I feel guilty about hiding so much from the people I love, but I don’t want to burden others with my secret life. I know they’d listen and try to help, but there’s so much they wouldn’t understand. These secret experiences are more real and essential to who I am and what I need to do than what’s happening in the parts of my life they see every day.

They’d probably think I was having a breakdown of some sort and needed to see a therapist. I can’t be sure I don’t have psychological problems, but what’s going on with me is more than that. Someday, someone will need to know what I’ve experienced, and that’s why I’m writing it out.

People here and at the hospice where I volunteer say I’m an empath, and I think they’re right, but it goes further, because I sense things about people and events I can’t prove are real. I’m driven by deep feelings and intuitions I can’t explain to others. And I’m getting one right now . . .

I feel it in the howling wind. My body is trembling, like I’m shivering with cold . . .

There’s someone out there I’m going to encounter soon. Someone who will alter my fate.

I don’t think I can write anything more tonight. The feeling is too overwhelming . . .

Two

Max’s Journal

My name is Max, I’m 18, and I am a predator. Legally spoken, my name is Ulrich, but that doesn’t go over so well here in the States, and it’s far too tedious to continue having to spell it out for people. Max is one syllable, says much about me, but not too much, and the spelling is self-evident even for illiterate American persons.

I see I’m doing what an American news reader would call “burying the lead.” As I was saying, I am a predator. Proudly so. If I said that to most people, they would think I was crazy or evil or both, but this is the extreme stupidity of most people, because homo Sapiens is categorized as a predator species—the apex predator of the whole planet on which it feeds. And yet, self-castrated members of this species use the word “predator” as a synonym for evil when they apply it to individuals who transgress their notions of social order.

Can you imagine a pride of lions calling a magnificent young lion a “predator” to suggest it should be despised and outcast? Yes, older lions have reason to fear an up-and-coming young lion. They may wish they’d devoured him before he became dangerous, but to call him a predator would only be a sign of respect.

But no, I don’t self-identify as a lion. Of the big cats, lions are too masculine for my tastes, too blunt force. I’m more lean, agile, and stylish, more like. . . a leopard. I am not a savage predator, but an elegantly fastidious one. I revere control and abhor messiness. I maintain my person, possessions, and spaces in perfect order and cleanliness. Isn’t this how cats conduct themselves? This is why I don’t care to talk or write in the sloppy, stupid, slangy way of my American “peers.” I operate with precision, effectiveness, and my own sense of style. I didn’t learn my polished demeanor from the random people around me, but from books and films that satisfy my standard of elegance.

I’m a stealthy, slippery operator, not a brutal killer type. I’m more into money and power than creating a body count. I’ve never been accused of an excess of kindness, but I have no interest in harming others as an end in itself. Nevertheless, I pursue my ends with ruthless determination and am not shy about employing deception and misdirection.

So, I am a predator in a general sense. Why wouldn’t I be predatory? I am a descendant of an apex predator species, so what could be more natural? And what could be more unnatural and foolish than members of an apex-predator species casting aspersions on one of their kind who proudly asserts an apex-predator identity?

I grew up with hypocrites who don’t consider themselves predators because they buy the flesh of other mammals sealed in plastic from the market. They celebrate bacon as a fun food, but if they saw someone frying up a puppy, they would call them a monster. And yet, it’s well established that pigs are more intelligent than dogs in many ways.

No, I don’t harm puppies, and for that matter, I don’t eat bacon or any meat, not because of any moral scruples but because it’s repulsive, and I’m made of finer stuff and eat according to my nature. So those who might call me a predator are nothing but weaklings unable to see anything clearly, even what they put in their mouths.

They are self-castrated wolves wearing sheeps’ clothing, while I prefer to be a lean and hungry wolf, cloaking myself so as not to

draw their attention unless it serves my purposes.

So, given that I don’t eat animals, why do I call myself a predator? I am referring to my essential nature as one who efficiently and ruthlessly stalks my quarry.

Since my sexuality is part of my essential nature, it too has a predatory aspect. Indeed, I stalk, or more precisely, stealthily surveil those few who draw my interest, though I have yet to cross any bright red lines. But give me time—I am, as I have said, only eighteen. Perhaps I’m joking, perhaps not—I can’t even be sure myself.

Maybe my grandiosity is an act I put on for my own amusement, maybe not. You may assume these egoistic things I say are merely adolescent bravado as befits my age—perhaps so, perhaps not. I have proven myself highly effective in the real world and have the most universally respected metric to prove it—money. However, other aspects of my agenda have yet to be fulfilled.

I am acknowledging my grandiosity here to examine it and ensure it’s not undermining my efficiency. I’m German, so of course, I’m into efficiency. I spent the first twelve years of my life in Berlin, but I’ve made any trace of accent disappear unless I bring it back for effect.

My Germanic aspects are still with me, but I’m no Nazi. I admire some of those infernally intelligent Ashkenazi Jews with whom I share a strange karma. The savants and swindlers among them fascinate me so long as they are highly proficient at what they do. Of course, I despise those who are inferior. And by those who are inferior, I mean almost everyone, but this is without regard to race.

My grandiosity and contempt need a place to be expressed because outwardly, I prefer to be underestimated and fly beneath the radar. Sometimes, it’s valuable to intimidate or impress with my upper-class demeanor, while at other times, it’s more effective to be a forgettable cipher.

So, you shouldn’t think what I flaunt here is how I show up in public. It is certainly not. Nothing could make me light up more as a target than to present as a privileged Caucasian male with high pretensions. In my earlier life, I did show haughty arrogance and disdain because there was no reason not to, and I was so often irritated by confinement and the pervasive mediocrity I had to deal with both at home and at the supposedly “elite” (in other words, mediocre plus money) prep school I was compelled to attend.

But now that I am out and about in the larger world, I have become a slippery and stealthy chameleon. For stalking and surveillance purposes, I sometimes forgo the elegant attire I prefer and wear baggy hoodies and similar clothing to present myself as a typical American teenager, unworthy of notice. I am an operator, and I’ve developed the tools and tricks of my personal tradecraft.

To sustain myself, I operate as a financial predator in the crypto and stock markets, where my ability to perceive deep patterns and short-term fluctuations has enabled me to accumulate significant wealth. Primarily, I utilize my abilities to identify patterns that others miss and apply my skills to global finance. Using a contrived identity, I bought and sold cryptocurrencies and stocks until I amassed a small fortune, which I’ve grown into an ever larger one. To keep my parents from questioning my activities, I applied to business schools and informed them that I was merely monitoring various market cycles to fulfill my ambition of becoming a hedge fund manager —a goal they could understand and approve. As a result, I need no help from parents or anyone to travel freely and live off the land so to speak.

I am now a legal adult and can do as I please—and I am doing as I please—but not impulsively. That is the way of stupid predators, foolish petty criminals unthinkingly driven by animal drives. Besides constructing a false identity for financial transactions conducted before I was a legal adult, I have crossed few legal lines, though I may soon. If I do, it will be judicious, tactical, and strategic to minimize risk. It’s not that I’m risk-averse in any cowardly way. I simply seek to maximize reward and minimize any dangers to my own person.

In my former life, before I liberated myself, I was judged defective because I lack empathy for inferior persons. I have also been diagnosed as having on-the-spectrum autism, because I lack sociability and can focus intensely on a subject that interests me. The lame psychiatrist who made this diagnosis, which I had self-diagnosed years before, was entirely ignorant of the established fact that autistic mutants exhibit psychic abilities. All of this is extremely well documented as anyone capable of doing an internet search can affirm. Those who have researched this have concluded that the rise in autism is part of an evolutionary advance leading to superhuman abilities. When I informed the shrink of this gaping hole in his knowledge of autism, he acted completely disinterested. But I could see him make a mental note of my comment as a pathological symptom– as if I had just spouted off a fanatical flat-earth theory or something like that. My autism is an asset, not a liability or pathology. Those who judge me—a perfect physical specimen with obviously superior intelligence—as defective only reveal their stupidity.

It feels like I am addressing an audience, though I can’t imagine who I would ever allow access to my journal. It could be a stunning posthumous publication, though I don’t plan on dying anytime soon, and perhaps with the advances in computational biology, I won’t have to. Alas, I currently have no backups, not even a clone who might grow up to resemble me. Yet another reason not to take unwarranted risks.

So, while I am still confined to this one body, I will continue to take meticulous care of it as an irreplaceable resource and tool of my will. Accordingly, I eat a highly refined diet and work out every day to maintain my slender but flawless physique.

Someone glancing at me sees a fit and immaculately dressed young man from a wealthy and privileged background, and there’s nothing inaccurate about that impression as far as it goes. From experience, I’ve learned that people find the stare of my blue-grey eyes disturbing, so I wear dark sunglasses. This way, people see of me only what I care to show. If needed, however, I can eliminate the sunglasses and be charming and impressive, but that requires a significant expenditure of energy, so I use this mode only when necessary.

Otherwise, I give people as little energy or attention as possible. Why should I do anything more than that? What is the point of a social transaction that provides no reward? Because I refrain from such irrational waste of energy, I’ve been judged a cold misanthrope. If it serves my purposes, I am certainly able to appear not only normal but charming and charismatic. But there was no motive to do this with my parents or at school because I knew I would soon discard that inferior life just as a snake molts a skin that’s too tight.

Instead, I focused my energy on improving my body, finances, and escape plan. Early on, I recognized the most obvious thing in the world—money is the universal resource and path to power. I also recognized the obvious things about myself— I’m a predator and superior to others.

And then, the day I turned eighteen, only a couple of months ago, I disappeared into my new life and identity. Employing contractors at a distance, I spent a considerable part of my fortune building a home base to my exacting specifications. Hidden in the dark deciduous woods of northern New England, from the outside it seems little more than an architecturally superb house, but hidden beneath is a highly secure and shielded sub-basement, part command center and part . . .

Well, now we come to the more controversial aspects of my identity and plans. And yes, these parts are questionable even to me because they represent most of my risk portfolio. Until an hour ago, when I created this encrypted journal on an air-gapped computer, I never considered putting my predatory identity and intentions into words. I did so to analyze my controversial aspects, because they tempt me toward considerable risks and are not as self-evidentially rational as the rest of me certainly is.

Obviously, what I’ve written above is a self-indulgence expressive of grandiosity and narcissism, but I need to let some of the steam off my large ego before getting to the real work of this journal, which is planning and self-analysis.

I must ruthlessly examine my potential flaws, the parts of myself that are not rational, and other parts that are hard to comprehend thoroughly. I must be unsparing in examining possible liabilities in my nature, but first, I must delve into certain aspects of my anomalous abilities, which are relevant to the riskier parts of my agenda.

Most of my abilities are rare but not unprecedented, except in their highly effective combination. From that perspective, I could be seen as functioning merely at the outer edge of the human performance envelope. But I also have talents outside that envelope, which are, therefore, harder to evaluate. For example, I can anticipate the timing of certain events, not just market fluctuations, but life events that provide few precursory data points. So, I cannot attribute my successful anticipations to logic or intuitive pattern recognition, but rather to something else, perhaps a form of clairvoyance.

Initially, I was dismissive of such a paranormal possibility, but extensive research ultimately convinced me otherwise. Investigating scientific evidence of future sensing immediately led me to a paper published in a prestigious peer-reviewed journal by a renown Cornell professor, Daryl Bem, an old, gay Jew with great credentials. When I investigated all the criticisms of his methodology, I discovered instead the irrational bias of his critics, establishment science, and Wikipedia against the paranormal. I may not be an expert on scientific methodology, but I have the financial metrics to prove my ability to apply probability and statistical analysis in the real world. Ultimately, Bem’s work was vindicated. After analyzing a number of replicated experiments, I’ve concluded that many paranormal abilities, especially clairvoyance and telepathy, have been scientifically validated.

Beyond what is likely clairvoyance, I also have an exceptional ability to read people, to sense their weaknesses and strengths (if any), and often know what people are thinking or about to say. Sometimes, it’s because they’re so predictable, but other times it seems telepathic. And once, when I was thirteen, I was able to recognize another telepath at an airport and make contact. I’ll have more to say about that encounter soon.

I make these claims, and yet I must admit that some of my strange perceptions raise the red flag of logic error in my mind.

For example, I have a persistent sense that I am not the offspring of my parents. I see no way such high-functioning mediocrities could have produced someone like me. Of course, it’s a common grandiose delusion of children to believe they are descended from royalty, etc., so perhaps it’s childish vanity causing me to doubt that I am merely the product of a sweaty parental transaction nineteen years ago. Perhaps a lucky cosmic ray hit this unexceptional combination of DNA to cause a massively favorable mutation. DNA from unexceptional parents can sometimes enter the mathematical lottery of genetic combination and produce an exceptional result.

Since childhood, I’ve recognized myself as a new human type, an advanced product of human evolution, anachronistically appearing in this primitive world of bustling primates. Perhaps evolution created me as a hedge against its main bet on AI, the new species overtaking the inferior one that gave rise to it. I’m speculating, of course. I just know my parents and environment are in no way sufficient to account for me.

There have been rare occasions where I’ve encountered someone who seemed like they might also be a new evolutionary type. But these perceptions lack evidence and may be deceived by my most irrational drive—my sexuality. I have detected what I perceive as anomalous superiority in a few other young males who are, like me, nearly perfect physical specimens.

Since they are also the type I’m attracted to, I realize how likely that is to create false positives. But looks alone are not sufficient to create anomalous radar returns. I’ve seen many visually exquisite specimens who entirely lack the special quality I’m looking for. What I seek is far rarer than mere physical beauty.

There was one boy at school who had what I considered at the time a paranormal level of charisma. He was certainly quite good-looking, even to my unrelenting standards, and his social and intellectual functioning were superior, if not anomalously so. I surveilled him without any of my attentions being detected.

Quite diplomatically and with considerable charm, I attempted to form a social alliance with him, but he politely rebuffed those efforts. Of course, he knew my reputation as a creature others found cold and disturbing, so there was no chance of making an unprejudiced first impression. It’s quite probable that he found the charm I turned on him, but not others, suspicious.

And then, as I continued my surveillance, he became less interesting. Indeed, he was an ideal physical specimen, popular and socially skilled, and he did gain admission to Princeton, but once I gained access to his devices, he revealed himself to be a false positive. He was merely the best animal in the herd of subpar creatures swarming around me at this particular school.

My disappointment was not just with him but in my own failure of discernment. Hormones and animalistic drives had created a kind of optical illusion out of someone who was merely a superior mediocrity. He remained physically attractive enough to arouse sexual interest, but I refuse to degrade myself by having a physical transaction with someone ordinary based on looks.

I am no mere meat puppet whose strings can be pulled by hormones. I consider my misperception of this boy to be an embarrassing failure, but also a valuable lesson not to repeat such a humiliating error of discernment.

Twice, while traveling with my parents—both occasions were in airports—my gaze was arrested by someone with a glow which made them stand out like demigods amongst the hustle and bustle of disappointing primates.

One of them was a young man who had a Norwegian decal on his luggage and possessed an ethereal beauty that was breathtaking. But now I suspect his beauty created another optical illusion on par with the boy at school. He also failed a test I now consider definitive. Though I stared at him for several seconds, he failed to notice me or my sharply focused attention. A true anomaly should be able to readily identify another.

The other person, however, I am certain was a true anomaly. Yes, he was beautiful and elegant with long, dark hair and exquisite bone structure. Anyone would have found him intriguing and mysterious. But he gave evidence of being far more than merely beautiful.

At first glance, I recognized him as a sophisticated and cosmopolitan Ashkenazi Jew. His appearance wasn’t stereotypically Jewish, but as a German, I’ve inherited an exquisite Jewdar and felt the pull of racial exoticism and karma. He must have been eighteen or nineteen, but he seemed older and strangely timeless. He was unselfconsciously elegant and graceful, a prince of his ancient race. I noticed he was wearing an expensive diving watch, likely an Omega Seamaster, and despite his cosmopolitanism, he carried an air of being on a physical adventure.

I sensed he was not merely traveling but on a mission of some kind. Anyone with discernment could tell he was trying not to draw attention, but he lit up more intensely than anyone I’ve ever encountered. I felt his intelligence as if it were a physical force and sensed a mind filled with secret knowledge.

It was obvious he was another neuro-atypical like me. I instantly felt the presence of another ultra-high-functioning on-the-spectrum mind. I could tell that he too was containing his stress at the sensory overload of rushing people in the airport.

And yet, even with all these perceptions of superior aspects, I could not rule out a false positive because he was so perfectly my type. According to scientific research, physical beauty creates a “halo effect” that deceives observers into overrating a subject’s intelligence and other positive qualities.

While I cannot be deceived by beauty alone, the boy at school taught me that if high beauty is paired with other superior attributes, I too am vulnerable to such a halo effect and might conflate ordinary superiority with anomaly. Therefore, if I perceive anomalous superiority in a highly attractive person, I must compensate for the halo effect with a higher standard of evidence than if I perceived such superiority in someone who is not my type.

The Jew quickly surpassed my high threshold of evidence. He sensed my scrutiny and turned toward me, his hyper-aware brown eyes locking onto my gaze. Time seemed to slow as I felt him reading me in a cool, analytical way. For a moment, the boundary between subject and object dissolved, and our minds linked, but I felt him limiting the telepathic flow between us.

I sensed the nature of his caution as ethical and respectful. I was only thirteen at the time, and he didn’t want to be intrusive and was certainly not going to commit the impropriety of approaching a thirteen-year-old at an airport. So, he limited himself to an acknowledgment of me as another anomaly and telepath.

The form of his acknowledgment, occurring during an extended moment of telepathic eye contact rippling through time, had a formal and elegant quality, as though he were presenting me with an engraved calling card. If only he had. Nevertheless, it was a level of recognition I’ve never received before or since, a priceless gift.

When he was sure I received it, he bowed his head toward me in a beautiful gesture of formal respect. After bestowing this blessing, he turned and walked swiftly away.

I am certain I did not meet him by chance, though he seemed as surprised by the encounter as I was. While the Norwegian was oblivious to my presence, the Jew had been instantly aware, and that, I now realize, is the first test. There must be mutual recognition.

Regrettably, I was too dazzled by the encounter to slip away from my parents and follow him. If only I had trailed him to his departure gate, I could have found a way into the flight manifest. If I’d even had the presence of mind to take a good photo, I could have searched for him that way. Instead, I let him disappear into the masses. I was only thirteen and still quite stupid in many ways. I lacked the quickness to recognize and exploit this fleeting window of opportunity.

And yet, I have an enduring perception that our paths are destined to cross again. I keep an eye out for him on my travels to this day.

Those few heartbeats of telepathic contact made a profound impression and created a lasting influence. I felt the quality of his mind and how we were alike and different. He was as coolly analytical as I was, with a similar ability to perceive hidden patterns in the world around him. But there was more feeling infusing his intelligence and a sense of ethical responsibility. Obviously, I lack those qualities, but I will admit to respecting them in him. He carried them in a way that emanated courage, depth, and seriousness.

If I were to meet him again, I wouldn’t try my usual strategies. He’s older and perhaps the one person I’ve ever viewed as a possible teacher. In that moment of telepathic contact, he seemed to know exactly what I needed—respectful recognition— and he gave it to me. He left me with an awareness of his essence, even a transfusion of it, and his gift has left its mark.

Though I have presented myself as a ruthless predator, his influence subtly shifted that aspect. It’s taken the form of the one principle I follow, which is not to needlessly cause harm to others. I may not be kind to others unless the pretense of such is to my advantage, but I do restrain my misanthropic nature from being overtly cruel.

Living by this one principle is a form of respect or honor owed to the Jew for the respect and honor he gave me. If we meet again, I know he’d sense if I indulged heedless malevolence, and he’d lose respect for me. I would be diminished in his eyes and might lose the chance to learn from his secret knowledge.

At this phase, though, my main desire is to meet an anomalous, attractive male person close to my age. I want an equal, but also someone I can dazzle with my abilities and resources. Freed from parental captivity, I roam the country in my newly acquired luxurious and high-performance vehicle—German, of course, a dazzlingly fast, customized Porsche Panamera.

The path of my hunt favors college and university towns as those seem the likeliest to attract the type I’m looking for. I can afford to stay in highly rated hotels with gyms, and my financial work is easily done from anywhere. Give me signal and a device—even a burner—and there is little I can’t orchestrate. Perhaps my hunting is merely driven by youthful hormones, but intuition tells me otherwise.

I am certain that somewhere out there, I will find my counterpart. I am not one to quote a primitive mystic like Rumi, but I do like his saying that what you seek is seeking you. In our suspicious age, however, there is a risk of encountering a counterpart who will refuse the time and persuasion needed to realize I am who they are seeking. Next time, I will not risk a rebuff or allow them to slip away without a trace. But before I take any risky step to extend the opportunity of mutual discovery, I will surveil a candidate to eliminate the chance of another false positive.

Once you gain access to someone’s devices and can study their communications, mediocrity becomes all too disappointingly apparent. If they pass my investigation, it may be necessary to make them an involuntary guest in the subbasement of my home base, allowing them sufficient time to recognize my unique value.

Obviously, involuntarily hosting someone in my subbasement would cross bright red legal lines and is the most controversial and questionable part of my plans. You may think such a step would violate my one ethical principle of avoiding unnecessary harm, but this is not how I see it. It would be a helpful intervention, a way to rescue someone with high potential from being subsumed by the cult of mediocrity.

I‘d prefer not to use such risky means, but I can foresee scenarios where I’d need sufficient time and control over the setting to win them over. There’d be no need for such measures if they were immediately willing to break with their former lives to ally themselves with me. But realistically, how likely is that?

Even when I’m in charming mode, people find me a little too intense for comfort. If they are currently enrolled in college or university, it will take persuasion for them to realize the self-castration of remaining a captive of institutionalized education when they could immediately gain access to power and wealth by joining forces with me. If I find just the right person, I’m confident that, given enough time, they’d realize the superior value of what I offer, but such persuasion cannot be rushed.

I readily admit that my plan is a risky and questionable first move to establish an alliance, but it will provide time to reveal my superiority, charm them, and demonstrate what a powerful ally I could be, financially and otherwise. Although I may have to extend my invitation in this involuntary way, I will not be taking advantage of them, but rather giving them an undistracted opportunity to recognize my value. My facility is secure but luxurious, and they will lack nothing except connectivity and the ability to relocate.

And yet, this plan obviously entails felonies, and as meticulous as my planning and execution would certainly be, risks cannot be entirely eliminated. I wouldn’t dream of sequestering someone unless I had overwhelming evidence of their anomalous nature. At a minimum, they must have keen self-awareness of being different, and I’d have to see evidence of this on their devices. Only a fool would take such a step without powerful reason to believe a successful outcome is inevitable.

Still, of all my intentions, this is by far the most dangerous. Think of the messy fiasco if I were unable to persuade them, and they wanted to blackmail me with kidnapping charges! In such a worst-case scenario, I might have to resort to irreversible measures to ensure my safety.

My controversial plan begs a central question that someone reading this could legitimately pose. If I’m such a flawless predator, why not just go solo? Why even look for a companion and accept so much risk?

All I can say is that I am a predator, not a machine, and, like my sexuality, the desire for a companion is an irreducible need. Although I agree with others’ perception of me as cold and lacking empathy, it doesn’t mean I am without social interest, just that I have lacked the opportunity to relate to equals. Is it not a kind of empathy that allowed me to recognize anomalous superiority in the Jew at first glance and share a profound telepathic state?

There is no social deficiency in me. It is merely that I’d been surrounded by horridly deficient mediocrities with whom I had no desire to socialize. The encounter with the Jew went far beyond mere socializing. I long for contact with another telepath where the exchange would be more than words or gross physical transactions.

To be objective about my motives, I must admit that my desire for control requires that such a relationship begin with an upper hand and a card or two up my sleeve. Otherwise, I might start such a relationship at a disadvantage. I have no experience in any sort of mutual relationship, or in physical intimacy, for that matter. Suppose they did? I would be at an enormous disadvantage.

Though I desire an equal, it is my reasonable expectation to be first amongst equals. I want someone who will admire and follow my way of seeking power in the world. But I’m not looking for a slave or someone I’d be obliged to constantly dominate. It would be evidence of mediocrity if a prospective counterpart could be fully controlled. Anyone who’d submit to domination would be highly disappointing. Sexually, I’d prefer if we could exchange such roles.

I want a true companion who can rise to my intellectual and aesthetic level. Obviously, this would be a rare person indeed but not unprecedented in my experience. Given that he was several years older than I, I bear no shame in admitting that the Jew was at a higher level of self-realization than I was at thirteen.

Nevertheless, I must make sure that my need for a companion is not one of those classic tragic flaws that causes the downfall of a young hero in so many stories and mythologies. No, I will certainly not risk such an alliance unless I find exactly the right candidate.

Meanwhile, just knowing that I have a secure facility and a substance that would harmlessly render them unconscious while I relocate them is itself exciting, a fetish perhaps. It is the pursuit of such a person that gives my travels and financial work a sense of direction and purpose . . .

Three

Tommy’s Journal

It’s happened—the thing I sensed coming last night.

I am out in the woods picking blackberries. My basket is nearly full when a wave of slowtime passes over me, and with it, an intense sense of déjà vu like I’ve been in this moment before.

I need to be alone when slowtime happens. Slowtime forces me to see into other people more than I want to—behind their thoughts and feelings. And that’s like disrespecting their privacy. So, I take my basket and disappear into the woods to hide out in my treehouse.

From its high cedar deck, I look out over the sea of leafy branches and rolling hills that form the valley I live in. Gusts of wind rustle the canopy of leaves around me. The wind calms as the sun breaks through the clouds, lighting up the forest with its golden rays.

The warmth on my skin melts my uneasiness. I undo the tie holding my hair and lie back on the deck. The grain of the cedar planks against my skin and the smell of the newly sawn wood make me feel like I’m on an old ship sailing under the sun.

A fresh wind carries the evergreen scent of fir trees from deep in the valley, bringing me back to where I am. My sensations become intensely vivid, like I’m feeling everything for the first time. I reach into the basket, wanting to taste the blackberries.

They’re sweet and smooth, almost bubbly, sliding on my tongue. My senses cross, and their flavor becomes a deep purple light flowing into me.

Slowtime stretches every moment.

A great horned owl soars into view. I can see the brown and white stripes of its wind-ruffled feathers in perfect detail. The owl is like a banner rippling in the sky, bringing a message. It passes overhead and screeches, sending a current of fear through me.

As the owl flies off, a strong gust of wind pushes dark clouds across the sun. I hear a distant rumble of thunder coming from the western part of the valley, followed by more gusts of wind. The sudden chill forces me to sit up and hug my knees to my chest for warmth.

The howling wind is making me shiver. The shivering builds until it becomes violent. It’s almost like a seizure or being electrocuted.

And then I become the electricity.

I erupt from my body into the howling wind, swiftly ascending toward the dark clouds above.

I look down and see my body still sitting there on the deck of the treehouse, shrinking away as I rise higher and higher. The windblown tree branches continue swirling chaotically around me, but it’s too weird to view myself this way, Intense vertigo overtakes me, like I’m about to plummet. A dizzy panic, and I drop—

Suddenly, I’m in my treehouse in the dark, feeling intense fear. I hear gunfire in the distance. It’s where I’ve been in my nightmares, but this time I’m not asleep. I hear my mom speak with great urgency, but she’s not beside me—she’s speaking in my mind.

“Tommy, everyone else is gone, but you must live, you’re needed for something important. There is one who will help you survive, but you must leave. Now!”

The urgency of her last command propels me to take action. I feel the horrible truth of what she said, everyone is gone, but you must live.

I realize what the gunshots mean. The Friends have been murdered, and I’m the only one left. The killer knows where I am, and he’s coming toward me.

There’s no time to even dress or put on my shoes. I open the hatch, race halfway down the rope ladder, and jump onto the ground, ready to run, sensing death is almost upon me.

And then I look behind me and see the robot with a raised gun. I know it’s not the killer, but the one who will help me survive. I hear a shot ring out, and it jolts me out of my body.

I find myself back on the treehouse deck, and it’s daylight again.

Was I killed by that shot? Killed in the vision?

My arms are wrapped around my knees, and I’m shivering. The sound of the shot still rings in my head.

The wind settles. Though the sky is still overcast, it’s no longer darkened by thunderclouds. The warmth of the humid air stops my shivering.

I sense someone is with me, watching. I can’t see anyone, but I feel their gaze emanating from a point suspended in space about ten feet beyond my treehouse deck.

I stare in that direction until an outline of light begins to form. From its center, a boy about my age begins to appear.

He’s glowing and not quite solid in the way I am. As his body takes on definition, I discover something terrible has happened. His clothes are burnt, and much of his skin is charred. I try to hide my shock at the sight of his burns. The fire hasn’t touched his face, so I focus on his intelligent, brown eyes looking deeply into me. I’m struck by how calm and aware he seems, even though he’s in such a terrible state.

I think of my volunteer work at the hospice. I’d been with old people as they transitioned at the edge of death. Sometimes they communicated with me. Other times, they’d just look back at their body and depart.

But he’s my age. He needs to live.

As I gaze into his eyes, it’s like I’m being seen for the first time. Understood for the first time.

I want him to live. I need him to help me understand what just happened—what’s coming—it feels like there’s something important we must do together—

Like knowing in a dream, I realize certain things about him.

We’re so different.

He’s grown up in a city world with books and complex ideas. His dark hair and eyes against his pale skin suggest an ethnicity I can’t name. We’re from different backgrounds and even different bloodlines. And yet, there’s a bond of brotherhood between us.

Whatever’s coming has brought us together. I sense he understands much of what I do about our encounter. His dark eyes are like portals of awareness, and I want to know the depths he’s seeing. It’s the moment to say something.

“Hey.” Despite the strangeness of the situation, I keep my voice calm and friendly. “I’m Tommy. What’s your name?”

“Andrew,” he replies.

“Andrew,” I repeat, the name lights up in my mind as though I knew it already. “Welcome to my treehouse. Can you—would you like to sit with me?”

He looks at me uncertainly. I smile and pat the deck to invite him to sit. He flickers for a moment and suddenly is sitting across from me. Closeness makes him seem more solid, and I realize he’s not only my age but almost exactly my size. I want to hug him, my usual way of greeting people, but I don’t want to shock the fragile sort of body he’s in.

“Where are we?” he asks.

“Vermont. A valley in the Green Mountains.”

He turns to look out, but as soon as we break eye contact, his body begins to thin. He looks back in a panic, and our gazes lock as we realize something.

We need to stay focused on each other to keep him in my world.

I slow my breathing and surround him with my energy to help him stay solid.

“What happened to you, Andrew?”

“I was. . .” Andrew hesitates, and his vision turns inward. “I found myself looking down at the wreck below. There were two smashed-up metal hulks. Smoke was coming from the one that was once our—”

He stops talking, and his eyes fill with tears. They cast downward as if he’s still seeing the wreck. He’s trembling, and I sense him trying to hold back his feelings. He’s afraid they’ll disturb me.

I’m afraid he’ll lose solidity again, but he gathers himself, and when he looks up, his eyes are haunted, but his voice is calm and almost trancelike.

“There was broken glass everywhere. Flashes of red and blue lights from emergency vehicles lit up the fragments like rubies and sapphires. It all looked so strange, but sort of eerily beautiful too. There was a feeling that everything was exactly the way it was supposed to be. The wreck was just something that unfolded in time—like a flower bud opening its petals.

“I let go of it and ascended into space. And . . .”

He seems confused, and he looks downward again. It’s like he’s realizing he shouldn’t tell me certain things. I keep surrounding him with my energy so he doesn’t fade out. When he looks up, his gaze steadies.

“I blacked out. And when I woke up, I was floating near your treehouse.”

“Well, I’m really glad you found me,” I say with a welcoming smile.

“I’m glad you found me, too,” he replies. “At first, you didn’t see me. I watched you. I saw you shivering, and it made me feel cold. Then, when you rose out of your body, I went with you, almost like we were the same person. I saw and felt with you.

“You’re in danger, Tommy, your whole world, and I want to help you—there’s something we’re needed to do.”

I let out a breath, grateful that Andrew experienced the vision with me. But then I feel a pang of fear. I sense our time is extremely limited.

“Where are you, in this world? I mean—are you in this world? How do I find you?” I ask, feeling a sense of desperation.

“I don’t think you can, Tommy—we’re not in the same time. But one day, I will find you.”

I’m about to ask him more, but something in his gaze quiets me. We look deeper into each other’s eyes and then . . .

We merge.

It’s like we fell into each other. We were still ourselves, only swirling together without our bodies. Two sides of the same being. I really can’t describe it any better than that. I saw with my soul instead of my eyes, like some kind of revelation.

It was a moment, or an eternity. A space outside of time. And then, we separate. We’re still sitting across from each other on the treehouse deck. Andrew gives me an intense look.

“Tommy—” he begins to say when a blinding electric shock arcs through his chest.

His body seizes, and he vanishes in a flash.

It happens so quickly, I can’t even react. The empty silence he leaves behind is crushing, and I’m afraid I’ve lost him forever.

He was ripped out of my world, and I’ll never know—What, Andrew? What were you going to say?

And then, I hear him.

“Tommy . . .”

His voice seems to stretch across space and time like it’s traveling an impossible distance to reach me. An echo of an echo.

“I will find you, Tommy.”

And then he is gone and only silence remains. I’m waiting for something more, sitting at the edge of the deck, listening like I’ve never listened before. But all I hear is the wind.

In my mind, the echo of his words trails off.

I will find you, Tommy . . .

I stay on the deck for quite a while—an hour, maybe longer—searching for a trace of his presence, hoping for something more. But he’s gone.

Before I climb down, I take a last look around. There are only treetops as far as I can see while the sun drops toward the ridgeline in the distance.

I don’t know if my words will reach him, but I whisper a promise into the silence.

“Andrew. . . we’ll figure it out.”

I feel the moment rippling in time.

That was only a few hours ago, but the encounter feels like something I always knew would happen—and writing about it, the words flowed out of me with a strange déjà vu feeling, like I’d written about it before.

Should I warn the others? But warn them about what?

I know visions can be more like dreams and shouldn’t be taken literally. It was all so absurd—a robot holding a gun like a person when police and military robots have built-in weapons.

If I tell anyone, they’re just going to say I had a bad dream or some kind of episode.

But it felt so real, and when I saw Andrew, I knew I wasn’t dreaming or just seeing a vision in my head. Andrew is real.

But if I tell them, it’ll just sound like crazy talk, and they might think volunteering at the hospice is making me unstable. And if I tell them anything, I’d really have to tell them everything—slowtime, quicktime, and my other visions.

I can’t stop thinking about Andrew. He said we aren’t in the same time, but that he’ll find me one day. I believe him, but that time feels far away.

The truth is, Andrew left me with a lot of really personal feelings about him, which is a little embarrassing to write about.

Andrew seems like the friend I’ve always been looking for, someone who understands me and all my strangeness. We have a deep bond, like we’ve known each other all our lives. At the same time, we’re so different.

Most of what I know is what I’ve learned here in my little community and from working at the hospice, but Andrew feels like he’s seen the wider world. I could tell he’s from a big city like New York. I’m just a farm boy compared to him, and yet he seemed as interested in me as I was in him.

I need Andrew to help me understand what’s happening to me, and it feels like, together, we could figure out what’s coming and what to do about it.

His eyes had so much inner knowing—it felt like he could see through anything and understood me perfectly, and when we merged. . . I don’t even know how to describe it—I wish I could experience it again. It’s like we became part of each other. It’s left me feeling he’s more than a friend—like some kind of soulmate.

Four

Max’s Journal

Writing this journal seems to have had the uncanny effect of advancing my purpose, as for the second time in my life, I have discovered a person who I am certain is a new evolutionary type!

I realize linking the journal to this event is not rationally justifiable, as correlation is not necessarily causation, and yet intuitively, I sense a noncoincidental relationship between the journal and the event. The simplest explanation is that I had a an unconscious premonition of the upcoming encounter, which spurred me to begin the journal.

Since liberating myself, I’ve been touring the Northeast, an area with a high concentration of elite colleges and universities. I recognized a practical advantage to conducting my search within a few hours’ drive of my home base to enable relocating someone. I was following a northward path when a problem with my new vehicle forced me to divert to Burlington, Vermont. Though the University of Vermont is probably not of sufficient caliber to attract the type I’m looking for, I decided to walk around Burlington while my vehicle was being checked.

In a neighborhood of local shops, I turned a corner, and there I saw him, a boy of maybe only fourteen or fifteen, working with a middle-aged man to unload beautifully made furniture from the back of a pickup truck and into a store showcasing local crafts. The boy defied my college-student demographic expectations, being inconveniently young and apparently not enrolled anywhere, as he was working in the middle of a school day.

At first, his physical beauty made me wary of another optical illusion effect. It had an uncanny aspect. It was not just the impossibly golden hair and green eyes—it was as if all parts of him, even the worn denim pants and flannel shirt he wore with sleeves rolled up, glowed with color and aliveness. I’ve never seen such radiance. Simply looking at him made me feel as if I were included in his mythic life, as if he were Huckleberry Finn passing me on his raft down the Mississippi.

Though I was outside his field of view and away from his line of travel to the front door of the store, he turned toward me, and in my whole body, I felt him reading me. And it was no casual recognition as I could tell he was as startled and struck by my presence as I was by his. As soon as we made eye contact, it became an immersive telepathic experience.

His energy was so different from the Jew, who instantly impressed me as an intellectual equal with a mind full of secret knowledge. But the way this boy read me was not detached and analytical. What emanated from him was more like a musical waveform imbued with deep emotional resonance and a hard-to-define mythic quality.

Time slowed around him, and his awareness seemed to take in all of me—what we Germans call a gestalt—in a moment.

The boy had an awareness difficult to categorize. It wasn’t intellectual intelligence, but rather a profound emotional recognition. He was so tuned in it seemed like if the eye contact lasted any longer, he would read everything about me.

He’s not an operator in the way I am, not someone who devises complex stratagems or employs deception. Everything about him was transparent and open for anyone to read, and yet that was not a weakness in his case, because others would be just as transparent to him. Whenever I heard someone call themselves an “empath,” they always turned out to be a highly neurotic person trying to get sympathy because they were triggered by all sorts of nonsense. But this boy was the real thing, and I got the unmistakable impression he could see right through to anyone’s intentions.

I assumed the man I saw him with was his father, as there was an evident bond of strong affinity between them, something I’ve never experienced myself or even observed between my “peers” and their parents. However, I knew such bonds between a parent and child must exist somewhere.

I retreated from the scene as soon as they entered the store, stopping only to capture a photo of the truck’s license plate. I proceeded down the block till I found a storefront shadowed by an awning where I could observe unnoticed. I pulled out the small Leica monocular I keep in my shoulder bag to surveil them from a distance.

Once the furniture had been unloaded and brought into the store, they raised the tailgate and drove away. That was my cue to enter the store, where the furniture they unloaded was already on display along with a selection of exquisitely crafted kaleidoscopes, and—impossibly fortuitous—next to the kaleidoscopes, a stack of trifold brochures containing an abundance of information about the boy and the man who was with him.

The man’s name is Matthew, a master carpenter and furniture maker, and the boy, Tommy, is not his son but his apprentice. Tommy. The name suits him well—the name of a wholesome American country boy to my ear. That it might deceive others into seeing him as simple country boy also pleases me. Tommy is my discovery.

The brochure included a photo of them working side by side in their workshop, where they live in a small, intentional community near the Green Mountains. The community is called “The Friends” and is devoted to permaculture principles and nonviolence. The brochure helpfully provided the URL of a primitive website for the Friends community and the crafts and produce they sell with contact information, address—everything I need to begin my surveillance.

Time slows again when I pick up one of the exquisitely made kaleidoscopes and—I realize this could be imagination—but it feels imbued with Tommy’s energy from all the meticulous hand labor he put into it. If necessary, I could probably lift his fingerprints and likely his DNA from this handmade object. I bring it to my eye and gaze into the stained-glass portal and see a fractalizing polychrome mandala lighting up like the birth of a new universe.

I hear someone approaching from the back of the store and look up to find an over-friendly older woman, apparently the store owner, walking toward me.

“Aren’t they just amazing!?” she says in an annoyingly loud and exclamatory voice. I notice she is without New England accent and sense she’s someone who came to Vermont in search of quaintness. A voluble sentimentalist no doubt, contemptible, but something I can use, so I restrain my extreme annoyance. I despise store folk greeting me or asking if I have any questions, as if the possibility of asking a question was something that would never have occurred to me without their prompting. Normally, I flash such intrusive retailers my Germanic death stare to stop their advance, but in this case, I hide my irritation since this woman might possess useful knowledge about Tommy.

“And those were delivered just five minutes ago!”

I take a deep breath to summon the immense energy necessary to animate my charming and ever-so-polite young man character, a laboriously contrived persona I loathe to put on and reserve only for situations where such a distasteful disguise is likely to yield a significant reward. Though I’ve learned to speak English with no hint of German, I decide to put on an egzzagerated Cherman accent and summon a flowery, faux nineteenth-century manner to portray an older American’s idea of an innocent, naïve, but well-bred European traveler amazed by everything in the New World. As I have said, I am a chameleon, and I sense this is the character that will elicit the volubility I require from this chatty woman.

“Oh, how lucky for me! Zese are quite vonderful! I vould love to purchase vone. Such exquisite craftsmanship. I assume zey vere made by someone local?”

“Oh yes, everything in the store is made by local artisans. These come from the Friends Community in the Green Mountains, and you just missed them.”

“Oh, vat a pity! I greatly admire ze true artisans.”

“Young man, I couldn’t agree with you more. So refreshing to hear from someone your age. We don’t get many young people in here these days. Most of them are just ordering factory-made things online and lack any appreciation or curiosity about finely made handicrafts.”

“Vhat a shame! I vas raised by my grandfazher, you know — part of a long line of cuckoo-clock makers in ze Schwarzwald, ze Black Forest region of Chermany. He always told me that if you want to truly understand a handmade object, you must know the hands that made it!”

“Well, I couldn’t agree more, young man! And the kaleidoscope you hold in your hand was made by a remarkable young artisan, even younger than you are!”

“Oh my! Even younger zan me! And to have achieved such superb skill already! Zis must be a most remarkable young person!”

“Yes, he is! Tommy is the sweetest and most polite fifteen-year-old boy I’ve ever met.

“When I asked Matthew—his teacher– if the other kids at the Friends Community are like Tommy, he gave me a serious look and said, ‘Nobody is like Tommy. He’s exceptional in every way, especially his kindness.’ He also told me that at fifteen, Tommy is already his equal in mastery of carpentry and furniture making. This new line of kaleidoscopes was the boy’s initiative.

“When I asked Tommy why he chose kaleidoscopes, he was just so humble. He said he couldn’t have dreamed of making anything were it not for Matthew’s training. Despite his modesty and shyness, he answered my every question I had about the design and construction of his kaleidoscopes. Then he smiled and thanked me for being interested in his work and told me how grateful he and his community were to me for showing their wares. His smile just lights up my whole day.

“What kid talks so appreciatively to adults? And what fifteen-year-old that good at anything refuses personal credit?

They really don’t need to thank me—I should be thanking them. Their products sell faster than anything else in the shop.

“Meanwhile, they have little reason to thank me as their products sell faster than anything else in the shop. And though I can see Tommy is shy and private, he always greets me by name, and his smile lights up my whole day.

“And every time they drop stuff off, every single time, they bring me a gift, essential oils they’ve made, a freshly baked pie, or organic produce. Today, he brought me blackberry preserves he picked and canned himself.”

She points toward an old-fashioned green glass jar with a handwritten label. Tommy’s handwriting. I feel an insane urge to steal this Tommy artifact, but the risk is unwarranted.

“Zis Tommy sounds like a remarkable young person indeed — so rare to find such modesty and kindness in zis day and age!”

“So true! But if other young people raised in the Black Forest are anything like you, they must also have wonderful Old-World manners.”

I won’t repeat every bit of this tiresome but valuable conversation, but suffice to say I greedily devoured every morsel of information she divulged.

So, unlike that encounter with that stealthy Jew in the airport who left not a shred of identifying information, I’ve already been given everything but Tommy’s birth certificate.

As fanciful as this may sound, it seemed part of the feeling I had when we first made eye contact of instantly becoming part of his mythic life, a life that seems not of this era but a distant past of farms and carpentry where instead of school, a boy might work as an apprentice living in a tiny community in the woods with his master. Does that not sound mythic in itself?

The oddest thing the shop owner told me was that Tommy volunteers at a hospice where his mother works as a nurse. Why would someone that age want the distasteful job of working with old, dying people? Perhaps it had something to do with his being an empath, but it still seems insanely altruistic. I began to fear he might be highly-Christian or something equally abhorrent, but she told me that though they follow a few

Quaker principles, they’re not a religious community.

The few kids who are part of this twenty-person settlement are homeschooled, she added, and their education is mainly through sharing in the work needed to support the community, which lives off the grid.

Of course, I bought the beautiful kaleidoscope so imbued with Tommy’s essence. It stands on my hotel room desk as a kind of Tommy talisman and effigy that makes him feel close.

The unfortunate news, from the surveillance point of view, is that the shop owner told me the community intentionally lives offline, and she can only communicate with them via email, which they check when they come into town.

These rustic details add to a mythic sense of Tommy as a kind of Huckleberry Finn, a storybook character from an earlier time incongruously living in the present age. He lives in a forest, working with his hands, and only occasionally witnesses the life of a small city when he comes into town to drop off furniture.

Since I knew exactly where to find him, I retreated to my hotel room to see what I could learn online. I soon discovered that his settlement is surrounded by national forest land, so it’ll be easy to surveil the community from a high vantage while camped in the nearby woods. I ordered a fabulously expensive Zeiss spotting scope—got to love those German optics—as well as high-end night vision equipment, a tent, and other things I’ll need to hide my vehicle and set up an observation post. Camping is permitted on national forest land, so all of this will be fully legal.

The settlement is at the bottom of a valley, so finding a nearby high observation spot will be easy. I have a strange feeling that everything’s been set up to facilitate my purposes. On the other hand, finding a way to encounter Tommy again without drawing attention from other members of his community will be tricky.

It’s strange how things work. I thought my search would lead me to another sophisticated operator like myself, and then the challenge would be to stay three or four steps ahead of them to earn their respect. But my strategies and tactics would not work on Tommy. He would simply feel what I was up to and see through to my underlying intentions.

And yet, these aspects of him, so inconvenient to my mode of operation, are at the heart of his unique magnetism. This boy is like a revelation of a principle of nature I hadn’t considered. I assumed attraction would be based on similarity, but the massive dissimilarity of this boy is key to his allure. I don’t want to call it an attraction of opposites as “opposite” is such an absolutism. We do have things in common, as we’re both anomalies and highly tuned in. Mutuality was evidenced by our ability to recognize and read each other immediately.

Instead of finding a slightly lesser anomaly, which would have given me the upper hand, I have found someone as anomalous as I am, but who embodies a different principle of nature. Such an alliance could be even more powerful, but I’m not sure how it would work. Or even if it would work. I’d face the immense challenge of adapting to someone whose nature is fundamentally different than mine.

I must confront red flags about my pursuit of this boy. On the practical level, I haven’t planned for the far greater legal hazards of someone underage. I assumed I’d find someone about my age, probably a college student.

There is nothing I value more than control. Control is implicit in being a predator and operator, and I make no apology for it. I’ve been derisively called a “control freak,” but I own that as a compliment. “Freak” is essentially a synonym mediocrities use for “anomaly.”

And yet, pursuing this boy runs dramatically against my need for control. If only he were eighteen like me, he’d be a free agent. If I persuaded him to join forces, there would be no legal lines crossed. However, as a fifteen-year-old, he’s not the controlling legal authority in his own life. Therefore, relocating him without the written consent of a parent or guardian would involve extreme risks that are hard to justify.

And then, even if I overcame that problem, this boy possesses an empathic awareness that would see through to my intentions, and I’d have no way to control that. Perhaps I could misdirect and deceive him within a short timeframe, but not in any ongoing alliance.

You likely assume from my many bold assertions of superiority that I have the fatal flaw of so many young males who overestimate themselves and what they can do. Actually, part of my superiority is an instinctive caution that leads me to be conservative in my strategies and tactics. I do not presume on luck, and I’m a shrewd realist about how things work.

Remember, I’m not American. I’m from the Old World, so I abhor the brash overconfidence of young American entrepreneurs. The media often glorifies the very few who succeed, while ignoring the far greater numbers who fail. Yes, my investments have an element of gambling, but I’ve always been careful not to put my principal at risk, and I’ve become wealthy by carefully risk-profiling every significant action.

To ensure my safety, I must establish a bright red line in my pursuit. Any notion I had of making the right person a guest in my secure facility is a zero-percent option in this case. Besides the staggering legal risk, he is too dissimilar from me to predict his reaction to such a coercive scenario. The only action available that passes my risk profile is surveillance.

The logical question is—given these factors, why am I pursuing him at all? One answer is that I’ve discovered a person who is even more of an anomaly than I was looking for, and I might learn interesting things just by observing him. But the real answer is one I must acknowledge is outside of logic.

A core intuition of significance tells me I am on the right track. The magnetism, attraction, and fascination I have for him are beyond logic, so I must proceed with extreme caution, and this journal is part of that caution. Let me define another red line. I will not consider any action beyond surveillance without returning to this journal for analysis and risk profiling.

My surveillance has already been highly successful, and I have learned a great deal about him with minimal effort and no risk whatsoever.

From The Friends website, I learned that their community sells organic produce and handcrafted products at a farmer’s market. Assuming Tommy helps with that, it could be a chance for a brief, casual encounter, though obviously not a sufficient opportunity to convince him he should break free of a life he’s fully invested in. Also, Tommy will recognize me from our first encounter, and he might suspect I’m stalking him. Especially since he’s a tuned-in empath, and I am stalking him.

Worse, even if I convinced him to leave his community and come with me, I’d be transporting him across state lines and committing an intimidating list of felonies. As a minor, Tommy’s consent would count for nothing if his guardians wanted to prosecute me. It’d be far too dangerous unless they gave me written permission, and how would I ever manage that?

But wait. . . now that I’ve asked the question, I see a possible answer. I could propose hiring Tommy for live-in custom carpentry work on my new home. To create a more plausible and wholesome scenario, I’d say that the house was purchased by my parents, and they’d put me in charge of supervising the finish work during my summer vacation from college. I was so impressed with the furniture I saw in the store that I knew they’d be perfect for the needed custom cabinet work on-site.

Of course, it would be too much to expect the master carpenter himself to relocate for such a project, but perhaps they’d be willing to hire out the apprentice? They could set the price for his services. The house has several unoccupied rooms where Tommy could stay in comfort. All meals and expenses included.

I have to admit, it’s quite a clever solution. I wouldn’t be meeting him again suspiciously, but with a plausible reason, and I actually need custom cabinetry and furniture.

However, the giant flaw in this plan is that they would almost certainly require me to supply them with the house address, so my headquarters and the involuntary guest facility would be known upfront. They’d probably ask to speak to my parents to confirm this arrangement.

This is far too risky. I need to continue surveilling, and given how well things have worked so far, there will likely be other unexpected opportunities.

Perhaps someone reading this might think me diabolical for plotting to separate this underage kid from his community. I claim no purity of motivation, but I have no intention of causing him harm. On the contrary, I wish only to liberate him from a life in the woods of little significance.

Obviously, no one else would see the situation as I do, but Tommy is clearly meant for more than carpentry and farming. His present life is holding him back from a greater destiny. A greater destiny he could find with me. So, if you think of this objectively, I have only his best interests in mind.

Five

Tommy’s Journal

I know this will sound paranoid, but I think I’m being watched. It’s been a few days since my last entry, and there’ve been more strange episodes I need to write about.

I was getting ready to leave the hospice in Bridgeton with my mom, and before we even left the building, my heart was pounding. I was shaking and scared, but I had no idea what it was about.

As soon as we walked outside, I saw a guy in a pickup truck parked at the corner staring at me and grinning. He had long, greasy hair and a scraggly beard, and his stare felt like a physical attack.

This is hard to even write about, but he had really bad sexual intentions toward me, and I could sense what he wanted to do to me—it was almost like he was doing it to me, and it was horrible like someone stabbing me in an alley. But that’s more like a comparison, and I don’t even want to put into words the images I saw.

Once we were in my mom’s car, I felt a little safer, but my heart was still pounding like crazy, and I had cold sweat all over.

My mom looked at me and said, “Tommy, what’s wrong? You’re so pale. Are you ill?”

I had no idea what to say, but I had to say something.

“I think I might be having an allergic reaction.” She put her hand to my forehead.

“You don’t feel hot,” she said. “Did you eat something at the hospice?”

“Yeah, a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.”

“Tommy, I told you not to eat there. It’s as bad as hospital food.”

As we pulled out, she told me everything that would be wrong with a peanut butter and jelly sandwich made by the hospice, but I was only half listening. I saw the truck pulling out just after we did. It had Maine plates.

“Tommy, from now on, I want you to make your own lunch and bring it with you, OK?”

“You’re right, mom. I will. I promise.”

I looked in the rearview mirror and saw the truck following us for a while, but then it turned off right before we left town. I had a feeling I’d seen that truck somewhere before.

And then, two days later, I saw it again.

I was back in Bridgton with Dorothy, picking up supplies. She needed me to load stuff into our community car because her knees are really bad.

The same truck with Maine plates pulled up. The sun was glinting off the windows, so I couldn’t see inside. But I could feel that man staring at me, and I felt like prey, like a mouse skittering beneath the watchful eye of a hawk.

I didn’t want to show it, so I hauled everything into our car without looking toward the truck.

And then, when we were pulling out, I had a terrifying vision. I saw the truck, the store, and the surroundings with my regular eyes, but with some other kind of vision, I saw something else, an evil creature or entity.

It looked something like a giant translucent spider, but with a weird head like an upside-down pear with large black eyes peering into me. I could tell it wasn’t of this world because it wasn’t reflecting the sun’s light, and it had no color, only a pale glow. It was like it was peering in from another dimension underneath or above this one.

Lines of energy, like nearly invisible electric guitar chords, ran down from the spider into the man in the truck. The spider was operating him like a puppet set on my track.

The vision lasted for just a few seconds, but it scalded my mind. It was as if the entity had peeled back the surface of the world to reveal other dimensions and designs beyond my comprehension, like a hidden hand moving pieces on a chessboard, shifting my destiny for its own purposes. Then the flap it opened on the surface of my world, dropped back.

A wave of nausea overwhelms me.

I keep my face turned away from Dorothy so she won’t see the spasms of sickness overtaking me, contorting my body, almost doubling me up. Dorothy is a super careful driver, so I know she’ll keep her eyes on the road, and if I don’t squirm too much, she might not notice, but then she does.

“Tommy, are you—”

“Can you pull over, please? I might need to throw up.”

She pulls over, and I walk into the woods, crouch down, and do a couple of dry heaves. The nauseous spasms pass, but I still feel sick.

While I walk back to the truck, I decide to tell Dorothy the story I told my mom about eating something at the hospice that disagreed with me. I hate lying to her, but I feel like I have to, and I know it would fit with what the Friends believe–and I believe as much as anyone–that food from the outside world is suspect and to be avoided.

When we’re back home, Dorothy offers to make me her tea for nausea with ginger, chamomile, honey-lemon, fennel, peppermint, and licorice. She’s our master herbalist. I thank her and tell her it’s exactly what I need, and she lets it rest. Dorothy is really great that way, she can sense when it’s better not to talk and just lets me be in my own space when I need that.

The tea helps, not just the herbs, but I can feel the love Dorothy put into it, and it calms me. As I sit on the porch of her cabin drinking the tea, I force myself to think back to the vision.

It had this really odd twist. I know people throughout time believed in evil entities like the devil, but that’s just like a distant fact in my mind, like knowing that the Egyptians built pyramids a long time ago. To actually encounter such an entity was a horrifying shock. But the strangest part was the sense it was revealing itself purposefully and not to frighten me, but almost for my benefit, like it wanted me to know things.

If that wasn’t weird enough, yesterday, another strange thing happened—another watcher appeared. I drove into Burlington with Matthew to drop off furniture at the store that sells our stuff, something we do about once every six weeks or so. There was a young guy who stopped to let us carry a heavy chest into the store, and I sensed him staring at me. I had a moment of slowtime, just a moment, which is not how slowtime usually works, and I turned to look at him, and. . . it was strange, not scary but not comfortable either. . . it was like we were reading each other’s minds.

It felt like he was a spy sent to find me or something like that. I’m not sure what I read from him, but he seemed highly intelligent and intensely interested in me, observing me, almost like his eyes were high-res camera lenses recording everything about me, every detail.

He was another watcher, but I don’t think he had any connection to the scraggly guy in the pickup truck. He was almost the opposite of that guy in the way he looked. Not a hair was out of place, and he was almost weirdly perfect, like a European model you’d see in a glossy magazine ad. He didn’t seem like someone from Vermont, but like someone you’d see in Paris or New York, someone from a super-rich family. But he didn’t seem like a spoiled rich kid—it felt like he was on a serious mission. He was so alert, and his whole mind focused on me like we were in an espionage movie, and I was the person he had been sent to find.

When we came out of the store to get the next item, he was gone. I sensed him still thinking about me, like he was watching from a distance, but he didn’t seem like a threat. It felt like I was in a movie with him, and he was going to bring me a secret message or something.

I realize anyone reading this probably thinks I’m a kid with an overactive imagination, but I’ve learned to trust my strange perceptions, and I’m sure there’s something to the intense feeling I picked up from him.

There’s got to be a deeper pattern playing out—all these strange encounters in just a few days—Andrew, the man in the truck, the entity, and now this young spy or whatever he is. The weirdness just keeps piling on, and I’m struggling,

trying not to be so overwhelmed that others will sense something’s wrong. I’ve got to keep myself together because I’m needed for something, something related to all these strange events.