A close friend of mine (the late Jack Spencer Savage) spoke to me about what he perceived as an inadequacy in himself. “When random people approach me, I often find myself cringing inside and wanting to escape.”

I told him that what he was experiencing made perfect sense to me and did not sound like inadequacy. His inner cringing, I added, is the healthy reaction of an introvert to intrusions of their interior space. Furthermore, this immunological response is directly related to a mainline evolutionary process.

Evidence supports teleological or goal-oriented evolution — and there is a central drive favoring novelty, interior space, and self-awareness. The evolution of life on this planet underwent a quantum shift when a process called “cephalization ” occurred. Cephalization means that nerve tissue is asymmetrically concentrated in one end of an organism. Cephalization, over myriad generations, eventually produces a head with sensory organs. This is the beginning of interiority — an organism developing a brain that allows it to build a neurological simulacrum of the outer world. This process reached its current zenith on this planet with homo Sapiens, the species that, as far as we can tell, possesses the greatest interiority.

The interiority of our species has been undergoing a growth spurt in the last few thousand years. Some say that up to the time of Homer, about 2800 years ago, there was no such thing as a private emotion. A dog, for example, does not have private emotions. If it feels an emotion, it acts it out with its body. Homer marvels that Odysseus can disguise his feelings. Today, we take this for granted, but 2800 years ago, it was apparently seen as a superpower. In the Fifth Century, Saint Augustine marvels that his friend Ambrose can read without saying the words aloud or even mouthing them. As Augustine put it:

“His eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud.”

From my point of view, individualized interior space is evolution’s pearl of great price. Individualized interior space is what makes us human. It’s a crucial variable that makes some human beings much more interesting than others. Highly collectived people, what Jung called “mass man” and I sometimes call “the hollow folk,” have diminished and low-quality interior space. Hollow folk are mostly formed from the outside by collective conditioning. Within them, we find a hodge podge of TikTok reels, flakey conspiracy theories, and gossipy voices inciting inferior emotions. When we interact with the rare person who has high-quality interior space, it can be like being invited into a temple. The inner space of Bach’s musical imagination is like the interior of a great Gothic cathedral with vaulted ceilings and stained-glass windows.

If you are consciously working on developing your individualized interior space (and it is unlikely that you would be reading this if you weren’t), then you are doing sacred, evolutionary work. Your individualized interior space is your sovereign domain and must be defended at all costs. From what do we need to defend it? Your sovereign domain must be defended from outside conditioning, sensory pollution, and the intrusion of distracting influences.

For example, let’s say you are sitting on a park bench writing in your journal. You are doing invaluable work in your sovereign domain. A bored stranger sits down next to you and, without asking permission to intrude on an obviously interior process, tries to engage you in a meandering conversation. Ill-informed, highly conditioned opinions come spilling out, a cascade of inferior thought forms making a bum’s rush into your sovereign domain where they prance about drunkenly like they own the place.

Some people feel that courtesy demands that they continue to listen. Because of social convention or misguided sympathy, they assume an obligation to surrender their sovereign domain to whoever demands it. I don’t make that assumption; instead, I believe that appropriate boundaries are what allow me to have a sovereign domain. As Robert Frost said, “Good fences make good neighbors.” In the present example, I would say, “You’ll have to excuse me; I’m working on something that just can’t be interrupted.” The small-talker can move on and find others who will, passively or willingly, surrender their sovereign domains.

I also believe in respecting others’ sovereign domains. One of the reasons I left public school teaching is that I don’t want to participate in compulsory education. Someone forced to listen to a teacher is experiencing a violation of his sovereign domain. I wish to enter someone’s sovereign domain only if I am welcome. For example, I am riding in a car with three other people. If I choose to speak, three people will be my captive audience. I feel a moral obligation to ask myself first: Is what I am about to say of sufficient information or entertainment value to these three specific others that warrant my intrusion into their inner space? I’ve ridden in cars and vans while valuable insights and imaginal creations were happening in my sovereign domain, only to have a self-appointed entertainer decide to perform a loud monologue consisting of jokes at which only they laugh. My nervous system does not allow me to tune out such a close proximity intrusion. The speaker violates my sovereign domain, but I must sometimes allow that. For example, let’s say the entertainer is the owner/driver of the vehicle who is doing me a big favor by giving me a ride. The car is his domain, and courtesy demands that he be allowed free speech in his domain. Therefore, I avoid captive situations where I must surrender my sovereign domain to all and sundry.

But there are many situations, such as public transport, where it is difficult to defend your sovereign domain. There is a type of person I call a “squawker” who feels that his loud, inane voice is God’s gift to the social matrix. This sort of person has loud cellphone conversations or erupts into explosive, caffeinated guffaws of idiotic laughter at various unfunny remarks in public places. I recommend carrying earplugs and/or noise-canceling headphones whenever you travel through collective spaces.

However, defending your sovereign domain does not mean you are like a tortoise retreating into your shell. Few things are as valuable or take up as much space in your sovereign domain as a significant other. Therefore, you need to be selective. You want to be able to invite significant others into your sovereign domain, but it is hard to do so when you are exhausted by unwelcome intrusions that will sometimes try to interpose themselves between you and significant relations. If you are having an intense one-on-one conversation with someone and a small talker seeks to intrude, politely but firmly set a boundary: “Sorry, this needs to be a one-on-one conversation.”

Often, however, what degrades our sovereign domain is not outside intrusion but inner chaos. Most people are oppressed by what Jung called “psychic entropy.” Their sovereign domain becomes filled with looping negative thoughts, dark emotions, and anxieties. For this reason, almost all people, even people who say they prefer solitude, report being happier in the company of others. Most psychopathologies, compulsions, eating disorder behaviors, self-mutilation, suicidal thoughts, etc., are more likely to happen when a person is alone. The presence of other people helps to fill the sovereign domain that would otherwise be ruled by psychic entropy.

Defending your sovereign domain, therefore, does not just mean having appropriate boundaries with others — it also means being able to deal with inner forces that compromise integrity from within. The price of inner freedom is eternal vigilance in our inner realm.

At difficult moments, we may find our sovereign domain filled with what the I Ching calls “the inferiors.” These are inferior sub-personalities typically driven by wants and impulses that need to be managed by a central, witness personality that defends the sovereign domain from the chaos the inferiors can cause if they are allowed to rule. If we tune into our sovereign domain, we will likely hear various voices speaking. Some are nagging, some are fearful, some just want to have fun, and so forth. When you detect a voice, ask it to come forward onto the inner stage, to step into the light of your awareness so you can see with whom you are dealing.

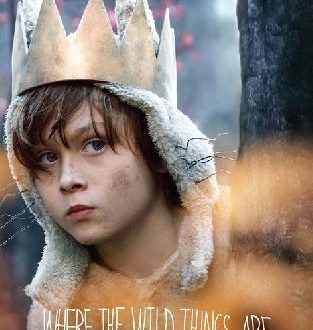

A great mythological version of the struggle to bring order to our sovereign domain is the live-action movie version of Maurice Sendak’s children’s classic Where the Wild Things Are.

Max is a young boy with an imaginative but chaotic psyche that causes him to act out dark, destructive impulses that he later regrets. Horrified by destructive things he has acted out at home, Max sets off in a small boat and journeys to an island where there are “wild things” — large monsters who appear to be human-animal hybrids. From my reading of the story, Max has traveled to his sovereign domain, where his untamed subpersonalities threaten to consume his central personality.

As Freud said, “Where id was, let ego be.” Max’s central witness personality is not aware enough of his unruly subpersonalities and must journey within to bring order to this chaotic realm. Just as he is about to be devoured by the wild things, Max commands them: “Be still.” They stop, and Max tells them that he is a king and that they must obey him. The wild things are relieved, letting him know they desperately want a king to lead them. One of the wild things pleads, “Will you keep out all the sadness?” Another wild thing acknowledges Max as the creator of this island realm: “You were the king, and you made everything, right?” Max gains their enthusiastic cooperation by allowing them to party and have fun at times. He announces, “Let the rumpus begin!”

Max lives safely with the wild things and even gets them to do his bidding so long as he maintains order. He wins the cooperation and enthusiasm of his inferior subpersonalities by keeping them busy on various creative projects and fun endeavors. But the wild things, like anyone’s cohort of inferior sub-personalities, are a difficult bunch, needy and neurotic, demanding and unable to set their own boundaries. When boundaries are set for them, they test them and see what they can get away with. Max has trouble with this because the boundaries he sets aren’t consistent.

Max’s main wild-thing ally, Carol, complains: “I can’t trust you — everything keeps changing.” Carol is giving Max crucial feedback — to be King of your sovereign domain, you need consistent boundaries that bring stability to the realm. Carol is also afraid, as all the wild things are, of an underground noise he hears that he calls “Chatter.” He expects Max, as the King (the central ruling personality), to protect them from this perceived threat. It sounds like the threat is the inner chatter of psychic entropy.

One of the more difficult wild things is Judith, who introduces herself to Max, “You don’t need to know me; I’m kind of a downer.” She also tells Max: “We want what we want. We want all the things that we want. Oh, and we want no more want.” Judith is the sort of sub-personality that easily feels neglected and can stir up rebellion. She asks Max: “How does it work around here? Are we all the same, or are some of us better than others? You like to play favorites, huh, King?” Instead of consoling Judith, Max childishly taunts her back, and she explodes into rebellion: “You know what? You can’t do that back to me. If we’re upset your job is not to get upset back at us. Our job is to get upset.”

Judith is also giving Max crucial feedback. We cannot manage our inferiors with harshness, bullying, or in any way descending to their level. According to I Ching scholar Carol Anthony, one needs to console the inferiors as a good dentist or doctor speaks to a child — “Now this will hurt, but only for a moment, and then I will give you a treat.” etc. To win the leadership of our inferiors, we must be seen as fair, just, and able to provide them with some fun and pleasure at times. When Max forgets these principles, his reign becomes endangered; the wild things begin to doubt that he is the King and threaten to devour him again.

To defend our inner process, we need strong outer boundaries. Within, we must reign as a just and compassionate ruler. Consider this an auspicious time to bring healthy order to your Sovereign Domain.

Highly related: Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

For more on subpersonalities see Aspects of the Self.

For inner intrusions see Dealing with Psychic Entropy

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle

ZapOracle.com home to the free 720-card Zap Oracle